What’s Medicare’s secret sauce for controlling costs? The agency sets provider prices. It’s still the prices, stupid, GoozNews, Merrill Goozner, Sept. 7, 2023 AB: What is fun is my being able to talk to these guys and exchange thoughts. Then I bring them to Angry Bear. Kind of under the weather yesterday and today. Got the chills and a headache. The Times’ Upshot columnists weighed in on Labor Day on a subject I’ve written about extensively over the past decade. Since passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, Medicare has chalked up a remarkable record in holding down health care spending, reducing its projected outlays by a stunning .9 trillion, according to the analysis. I was glad to see the Times finally pay attention to this

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: Healthcare, Hot Topics, Merrill Goozner

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

NewDealdemocrat writes January JOLTS report: monthly increases, but significant downward revisions to 2024

What’s Medicare’s secret sauce for controlling costs? The agency sets provider prices.

It’s still the prices, stupid, GoozNews,

Merrill Goozner, Sept. 7, 2023

AB: What is fun is my being able to talk to these guys and exchange thoughts. Then I bring them to Angry Bear. Kind of under the weather yesterday and today. Got the chills and a headache.

The Times’ Upshot columnists weighed in on Labor Day on a subject I’ve written about extensively over the past decade. Since passage of the Affordable Care Act in 2010, Medicare has chalked up a remarkable record in holding down health care spending, reducing its projected outlays by a stunning $3.9 trillion, according to the analysis.

I was glad to see the Times finally pay attention to this reality. While editor of Modern Healthcare, I first wrote about it in my weekly column in 2013 (Headline: “The healthcare spending slowdown: Don’t underestimate the role of government in enforcing change”); I opined periodically on the persistence of the trend (see here and here).

Unfortunately, the second sentence in the Times story’s headline, “A Huge Threat to the U.S. Budget Has Receded. And No One Is Sure Why” was very misleading. The story itself offered a number of partial explanations for why Medicare succeeded in holding its per-patient outlays (the measure the Times chose to use) relatively constant:

- The Affordable Care Act and a 2011 Congressional budget act mandated reduced payments to medical providers (hospitals and physicians);

- Doctors, nurses and hospital administrators became more cost-conscious because of changes in federal policy. Those policies (not mentioned in the story) include penalties for hospitals with inadequate safety and excessive readmission records, and a host of pilot projects encouraging physicians and hospitals to deliver greater value for the dollars Medicare spends.

- Advancing technology allowed many procedures to move to less expensive settings outside hospitals. And,

- The drug industry is coming up with fewer blockbuster treatments (taken by millions of people), even as it still generates exorbitant profits by setting very high prices on drugs that treat fewer people.

But the story had one major oversight. It failed to mention the trend in hospital and physician prices that Medicare pays. Over the past decade, much of the outrage around medical spending has focused on the outrageous prices charged by hospitals and some physician practices. It led to passage of the 2020 No Surprises Act, which outlawed billing patients for charges levied by non-network providers.

But those skyrocketing prices only took place in the private insurance market — not Medicare, which sets the prices it pays hospitals and physicians for different services through an annual rule-making process. While few people outside the medical-industrial complex pay attention to what are officially known as the Inpatient Prospect Payment System (IPPS) and Outpatient Prospective Payment System (OPPS) rules, they are in essence gigantic price-setting operations, often running well over a thousand pages in length. State agencies that oversee Medicaid piggyback on those prices — usually at even lower rates.

Each year, the health care trade press covers the adoption of those rules. Over the past decade, the process went something like this:

- Medicare proposes increasing payment rates by next to nothing.

- The affected stakeholders scream bloody murder in comments to the proposed rule.

- Medicare issues a final rule that raises rates by 1% to 2%.

This year was no exception, although prices and total payments are rising by a slightly higher rate due to rising wage costs. In April, CMS proposed hospitals receive a 2.8% increase in reimbursement rates. In August, after receiving more than 3,250 comments from interested parties, CMS raised its average reimbursement level by 3.1%, well below last year’s inflation rate.

Meanwhile, what was happening to private sector rates? They shot up by about 4% to 5% in many years over the past decade. This morning, the Wall Street Journal reported the annual survey results on employer health care costs from the usually accurate Hewitt and Willis Towers Watson employee benefits consulting firms. The surveys predict private insurace rates will rise by 6.5% or higher for 2024, “the biggest in more than a decade.”

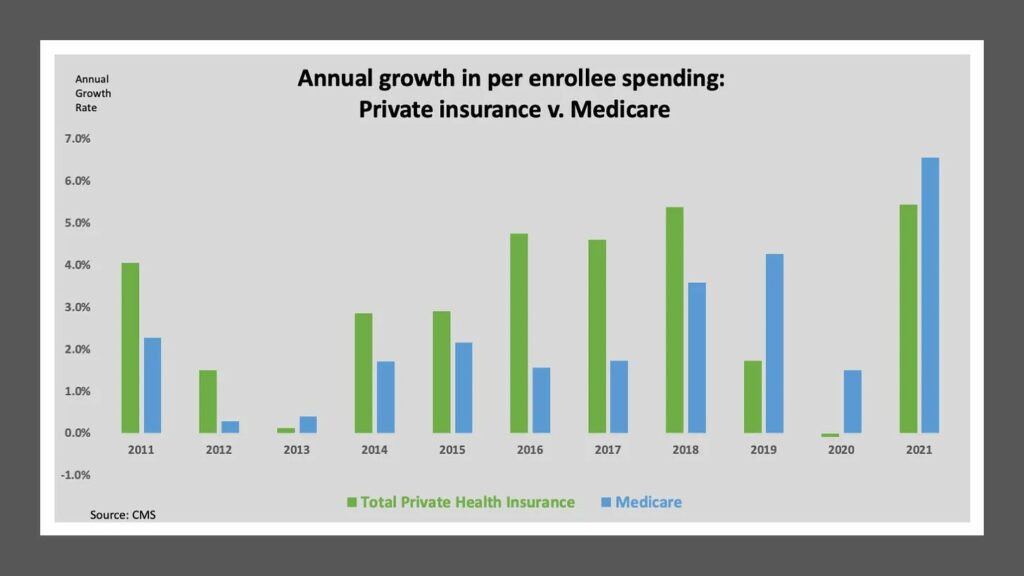

The chart below compares the average annual increase in per beneficiary costs in Medicare (the Times measure) to all private sector plans (employer-based, the individual market, and the Medicare supplemental insurance market). Most years (and especially during the Obama administration), Medicare spending per beneficiary went up at a much slower rate. In aggregate, Medicare costs per beneficiary went up 29% between 2010 and 2021 while private sector costs per covered life went up 39%.

Why don’t employers do something about it?

I’ve often wondered why employers haven’t gone to war against providers who overcharge them for health care services and the insurers who fail to negotiate lower prices on their behalf. Employer organizations like to complain about rising health care costs. But as marketplace participants, they seem to do very little about it.

A new study in the latest Health Affairs suggests their inattention is even worse than I imagined. Researchers at the Health Care Cost Institute, which has compiled a massive claims database, compared the prices paid for services by employers who buy their health care coverage from private insurers to the prices paid by employers who self-insure. They found the self-insured paid significantly higher prices among the 19 services they reviewed, with the highest differentials coming in the prices paid for procedures, lab tests and emergency department visits.

For instance, an endoscopy on average cost 8% more for the self-insured compared to those who purchased insurance policies where the insurance company is fully at risk if medical costs rise above premium payments. Colonoscopies cost 6% more on average. A complete blood count was 5% higher.

Overall spending by self-insured plans was about 10% higher, according to Aditi Sen, the research director at HCCI. I asked her why large companies who self-insure allow themselves to get hosed by hospitals and physician practices.

“The third party administrators’ incentives are not necessarily aligned,” she said. “They’re not the ones on the hook. Employers are on the hook. You would think they should be able to do some shopping around. But, the fact is, in a lot of cases, there is a lack of real time information which is foundation to any efforts to track and manage spending. Employers in a lot of cases don’t know the prices they’re paying. They don’t have access to the data that is theirs.”

While the new hospital price transparency law was designed to rectify that situation, employers, even the largest ones, rarely have the in-house expertise needed to pull and compare prices. Most operate in multiple states, which compounds the complexity of the task. That turns most self-insured big firms into price takers.

A few self-insured employers are taking matters into their own hands. They are forming non-profit alliances to negotiate lower prices on their members’ behalf.

They include over 300 self-insured employers with over 100,000 covered lives in the Wisconsin Alliance (it also includes some operations in adjacent states). They negotiate jointly with providers over pricing. Indiana’s major employers has formed a similar group. A group of seven counties in Colorado with over 8,000 employees recently organized the Peak Health Alliance to negotiate prices with providers.

The U.S. has a long history of farmers, consumers and small businesses forming non-profit cooperatives to engage in collective activity that furthers their own economic interests. I hope more self-insured employers explore that path in the years ahead. It would be a good first step in actually engaging in improving their employees health — a far better strategy than the failed wellness programs that remain in vogue with many employers.

Drug price negotiations will help … a little

AB: as far as I know pharma is still a small part of healthcare costs. “The 2023-2024 Journal’s Impact IF of Pharmaceutics is 6.525%, which is just updated in 2024.”

Health care prices are very much in the news these days, but it is drug prices that are getting the most attention. While giving Medicare the right to negotiate those prices is long overdue, let’s not pretend this is, to use President Biden’s words, a very big deal.

The Congressional Budget Office — the official arbiter in such matters — projects the government will only save $98 billion over the next decade from negotiating better prices for a handful of top-selling drugs. In a country that spends $4 trillion annually on treating its sick, that amounts to savings of two-tenths of one percent per year, a rounding error.

The most important savings for seniors will come from the $2,000 cap on out-of-pocket spending for drugs that begins in 2025. Unfortunately, the cap won’t apply to drugs administered in physician offices and clinics (Part B drugs), which includes many of the 10 drugs on the government’s initial target list for negotiations.

Big Pharma has overreacted, of course, by filing multiple lawsuits and trotting out its tired argument that lower prices will harm innovation. In an op-ed in yesterday’s New York Times, Larry Leavitt of KFF (the health care think tank formerly known as the Kaiser Family Foundation) lists all the reasons why that isn’t true:

- Government-funded basic science is the driving force behind every significant medical breakthrough, and that will continue “irrespective of curbs on prices.” (For more on that subject, you can read my 2004 book on the subject, “The $800 Million Pill,” still available from the University of California Press.)

- Many of the new drugs Big Pharma brings to market hardly qualify as breakthroughs (they’re so-called me-too drugs, replicating the action of drugs already on the market), or they represent marginal improvements over older drugs coming off patent (like having to take the drug once a day instead of three times a day).

- Legitimate breakthrough treatments will still get at least nine years of non-negotiable pricing after FDA approval in the case of small molecule pills and 13 years for injectable biologics, enough time to “reap substantial profits before having to submit to negotiation.”

- And, worst case scenario, the CBO projects negotiated lower prices will only result in 13 fewer drugs coming to market over the next three decades — a tiny share of the 1,300 new drugs expected over that period.

I’d add a fifth reason: If the government actually created a system that eliminated excessive pricing across-the-board, it would focus industry’s R&D efforts on legitimate innovations, the kind that justify higher prices for a brief period of time.