AB: I am always looking for these types of articles. They offer up explanations on how certain government policies and acts impact the nation’s economy and its citizens. Been a while since I looked at the 2001 and 2003 tax breaks. Steve Roth and I were exchanging emails on the more recent Republican 2017 tax break. There is so much wrong with these tax breaks. The latest one passed using Reconciliation. The 2017 tax break for the 1-percenters has yet to be neutral in its impact on the budget. Indeed, it has cost trillion in lost revenue and then some. Two Parts to this. Second Part tomorrow. ~~~~~~~ Testimony of Samantha Jacoby, Senior Tax Legal Analyst, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Before the Senate Committee on the

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: 2001, 2003, 2017, politics, tax breaks, Taxes/regulation, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

AB: I am always looking for these types of articles. They offer up explanations on how certain government policies and acts impact the nation’s economy and its citizens. Been a while since I looked at the 2001 and 2003 tax breaks.

Steve Roth and I were exchanging emails on the more recent Republican 2017 tax break. There is so much wrong with these tax breaks. The latest one passed using Reconciliation. The 2017 tax break for the 1-percenters has yet to be neutral in its impact on the budget. Indeed, it has cost $2 trillion in lost revenue and then some.

Two Parts to this. Second Part tomorrow.

~~~~~~~

Testimony of Samantha Jacoby, Senior Tax Legal Analyst, Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, Before the Senate Committee on the Budget.

After Decades of Costly, Regressive, and Ineffective Tax Cuts, a New Course Is Needed

Center on Budget and Policy Priorities

Chairman Whitehouse, Ranking Member Grassley, members of the Committee, thank you for the opportunity to testify before you this morning at this important hearing. I am Samantha Jacoby, Senior Tax Legal Analyst at the Center on Budget and Policy Priorities, a nonpartisan research and policy institute in Washington, D.C.

In my testimony, I will make three main points:

- First, tax cuts enacted in the last 25 years. The tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 under President Bush were made permanent in 2012. Those enacted in 2017 under President Trump gave windfall tax cuts to households in the top 1 percent and large corporations, exacerbating income and wealth inequality. These tax cuts cost significant federal revenue, adding to the federal debt and limiting our ability to invest in policies that broaden opportunity and contribute to shared prosperity.

- Second, extending the Trump tax cuts that expire at the end of 2025 would continue to mostly benefit the well-off and, if not paid for, would add considerably to the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges. Permanently extending the cuts would benefit households in the top 1 percent more than twice as much as those in the bottom 60 percent as a share of their incomes — providing a roughly $41,000 annual tax cut for the top 1 percent compared to $500 for households in the bottom 60 percent, on average — at a cost of around $300 billion per year. This would be on top of the large benefits high-income households will continue to receive from the 2017 tax law’s permanent provisions.

- Third, instead of doubling down on the failed trickle-down path of the Bush and Trump tax cuts, policymakers should set a new course by partially reversing the 2017 law’s flawed corporate tax cut, strengthening its international tax provisions, and reconsidering the tax code’s large tax breaks for high-income and high-wealth households. Doing so would make the tax code more progressive and raise substantial revenues. Such revenue could be used to address the nation’s long-term fiscal challenges and pay for important policy priorities. This approach stands in stark contrast to the House Republican debt limit bill, which would force deep cuts in a host of national priorities; leave more people hungry, homeless, and without health coverage; and make it easier for wealthy people to cheat on their taxes.[1]

The Wealthy and Corporations Have Received Massive Tax Cuts in Recent Decades

U.S. policymakers have substantially reduced taxes for wealthy households in recent decades. The 2001 and 2003 Bush tax cuts[2] reduced individual income tax rates, taxes on capital gains and dividends, and the tax on estates, all of which provided the largest benefits to the highest-income taxpayers. Though policymakers let many of the Bush tax cuts for high-income households expire in 2013, the 2017 Trump tax cuts again lowered individual income tax rates (including the top rate) and weakened the estate tax, so that it applied only to the wealthiest estates: those worth more than $11 million per person or $22 million per couple, indexed for inflation. The 2017 law also created a large new tax deduction on “pass-through” business income (business income from partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships) and enacted large and permanent tax cuts for corporations.

Taken together, these tax cuts disproportionately flowed to households at the top and cost significant federal revenues, adding trillions to the national debt since their enactment.[3] By shrinking revenues, these tax cuts limit policymakers’ ability and willingness to make public investments that pay off in tangible and important ways for individuals, families, communities, and the country as a whole.

Bush Tax Cuts Disproportionately Benefited High-Income Households

The 2001 tax cuts dramatically reduced the top four marginal income tax rates.[4] The top rate dropped from 39.6 percent to 35 percent, and the next bracket fell from 36 percent to 33 percent. The 2001 law also phased out the estate tax, repealing it entirely in 2010.

The 2003 law cut taxes on capital gains and dividends. Before the law, long-term capital gains were taxed at 20 percent. Dividends were subject to ordinary income tax rates. The law reduced the rate on long-term capital gains and qualified dividends to 15 percent.

In addition, the tax cuts included three components often referred to as “middle-class” tax cuts. A new bottom income tax rate of 10 percent was imposed. An increase in the Child Tax Credit from $500 to $1,000 per child and changes made many working families with low incomes eligible for the credit. “Marriage penalty relief” reduced taxes for some married couples. Many higher-income people benefited from these provisions as well.[5]

The largest benefits from the Bush tax cuts flowed to high-income taxpayers. From 2004-2012 (the years for which the Tax Policy Center (TPC) provides data that are comparable from year to year), the top 1 percent of households received average tax cuts of more than $65,000 each year, totaling nearly $700,000 in tax cuts over this period.[6]

High-income taxpayers also received the largest tax cuts as a share of their after-tax incomes. In 2010 the tax cuts were fully phased in. It raised the after-tax incomes of the top 1 percent of households by 6.7 percent. This while only raising the after-tax incomes of the middle 20 percent of households by 2.8 percent.[7] The bottom 20 percent of households received the smallest tax cuts, with their after-tax incomes increasing by just 1.0 percent.[8]

These cuts lost significant revenue: the cost of the tax laws enacted during George W. Bush’s administration is equal to roughly 2 percent of GDP in 2010.[9]

Evidence suggests that instead of “paying for themselves” by delivering increased economic growth, as advocates promised, the tax cuts enacted in 2001 and 2003 — particularly those for high-income households — ballooned deficits and debt and contributed to a rise in income inequality.[10] And there is little evidence they boosted growth. An analysis of the tax cuts by Brookings Institution economist William Gale and Dartmouth professor Andrew Samwick, former chief economist on George W. Bush’s Council of Economic Advisers, found that “there is, in short, no first-order evidence in the aggregate data that these tax cuts generated growth.”[11]

Nearly all of the tax cuts were to expire at the end of 2010. Policymakers extended many of their provisions for two years as part of a budget deal in December 2010. This agreement reinstated the estate tax starting in 2011, but with a lower tax rate and higher exemption levels, applying only to the wealthiest estates (those worth more than $5 million per person or $10 million per couple, indexed for inflation). And in 2012 policymakers agreed to make permanent the tax provisions affecting households with low and moderate incomes, but allowed certain tax rate cuts that affected only the highest-income taxpayers to expire, including restoring the top income tax rate to its previous level of 39.6 percent. This agreement made about 82 percent of the cost of the Bush tax cuts permanent.[12]

Trump Tax Cuts Created New Costly Tax Advantages for the Wealthy

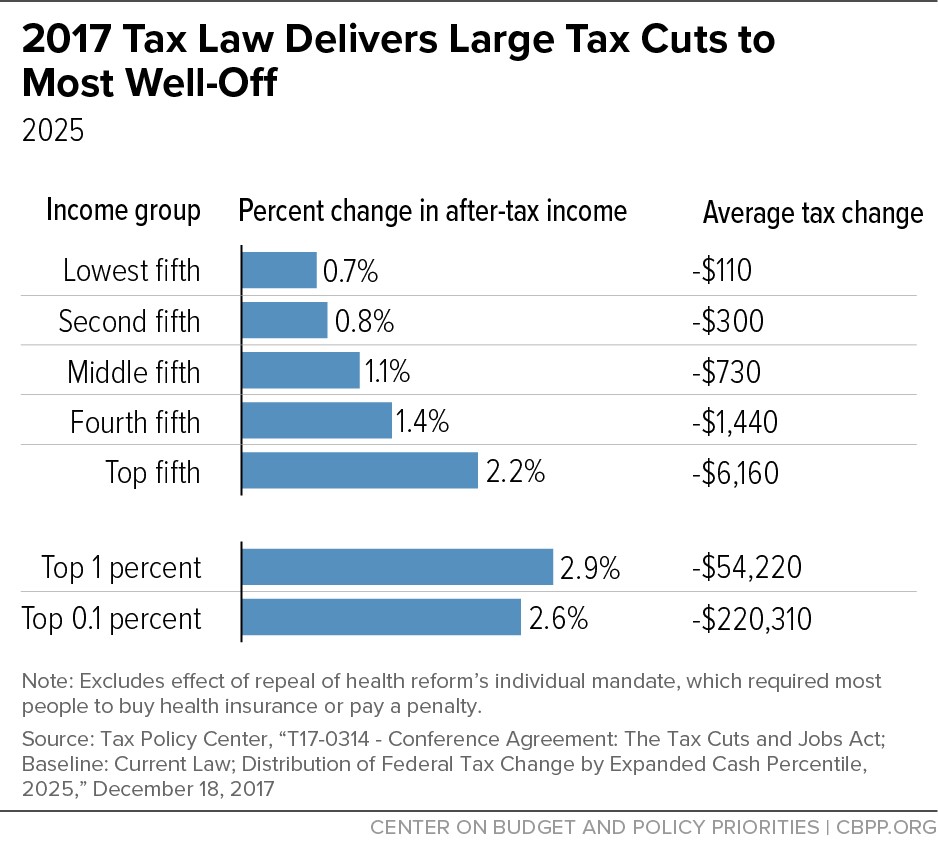

Like the Bush tax cuts, the tax cuts enacted in 2017 under President Trump benefited high-income households far more than households with low and moderate incomes. The 2017 tax law will boost the after-tax incomes of households in the top 1 percent by 2.9 percent in 2025, roughly three times the 0.9 percent gain for households in the bottom 60 percent, TPC estimates.[13] The tax cuts that year will average $54,220 for the top 1 percent — and $220,310 for the top one-tenth of 1 percent. (See Figure 1.) The 2017 tax law also widens racial disparities in after-tax income.[14]

The law’s tilt to the top reflects several costly provisions that primarily benefit the most well-off:

- Large, permanent corporate tax cuts. The centerpiece of the 2017 tax law was a deep, permanent cut in the corporate tax rate — from 35 percent to 21 percent — and a shift toward a territorial tax system, which exempts certain foreign income of multinational corporations from U.S. tax. At a cost of $1.3 trillion over ten years,[15] the deep cut in the corporate tax rate was the most expensive provision of the 2017 tax law, largely benefiting the most well-off. TPC estimates that over a third of the benefits from corporate rate cuts flows to the top 1 percent of households.[16] Proponents of these regressive corporate rate cuts argued that the benefits would trickle down in the form of broadly shared economic growth.[17] But a careful new study from researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, the Federal Reserve Board, and the Joint Committee on Taxation (JCT) finds that none of the earnings gains from the 2017 corporate rate cuts accrued to the bottom 90 percent of the income distribution, and this group received just a small fraction of the overall economic gains.[18]

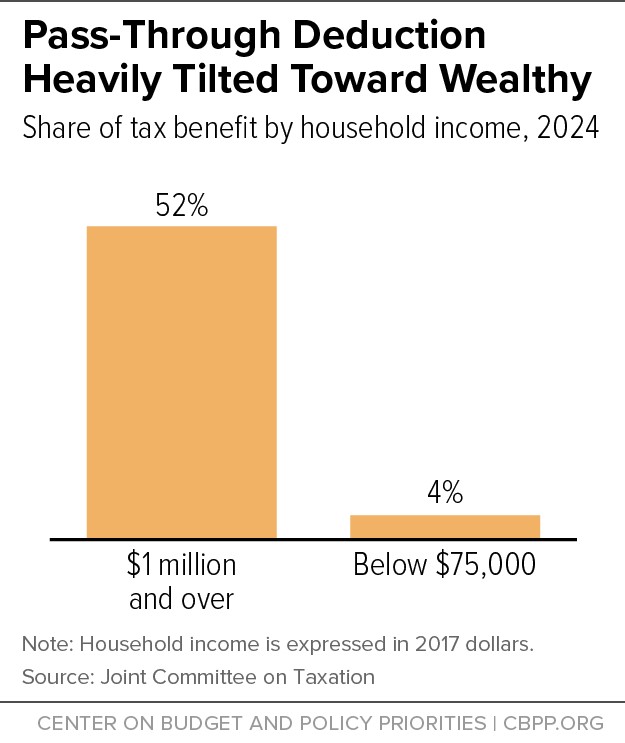

- 20 percent deduction for pass-through income. The law adopted a new 20 percent deduction for certain income that owners of pass-through businesses (partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships) report on their individual tax returns, which previously was generally taxed at the same rates as wage and salary income. The deduction costs around $50 billion a year through 2025[19] and its benefits are highly tilted toward the wealthy; over half of its benefits will go to households with more than $1 million in income in 2024, according to JCT.[20] (See Figure 2.)

- Cutting individual income tax rates for those at the top. The law cut the top individual income tax rate from 39.6 percent to 37 percent for married couples with over $600,000 in taxable income. By itself, this provided a couple with $2 million in taxable income a $36,400 tax cut. The law also weakened the alternative minimum tax (AMT), which is designed to ensure that higher-income people who take large amounts of deductions and other tax breaks pay at least a minimum level of tax. The law raised both the AMT’s exemption threshold and its phaseout, delivering another tax cut to affluent households.

- Wealthy households benefit the most from the deduction because they receive most pass-through income,[21] they get a much larger share of their income from pass-throughs than the middle class does,[22] and they receive the largest tax break per dollar of income deducted (because they are in the top income tax brackets). The deduction also creates new opportunities for high-income taxpayers to game the provision to maximize deductions.[23] Complex and valuable tax benefits like the pass-through deduction encourage taxpayers to push the boundary between lawful tax avoidance — itself engaged in by people with access to well-paid tax advisors — and unlawful evasion, and plummeting pass-through audit rates give them more leeway to do so.[24]

- Doubling the estate tax exemption. The law doubled the amount that the wealthiest households can pass on tax free to their heirs, from $11 million per couple to $22 million, (indexed for inflation). The few estates large enough to remain taxable — fewer than 1 in 1,000 estates nationwide — will receive a tax cut of $4.4 million per couple.[27]

Extending the Trump Tax Cuts Would Double Down on the Law’s Flaws

Most of the 2017 law’s corporate tax provisions are permanent, but nearly all of its other changes — including changes to the individual income tax and the estate tax — are set to expire after 2025. Extending all of these provisions would be an expensive policy mistake, costing around $300 billion per year.[28]

These expiring provisions include some provisions affecting families with low and moderate incomes, but often in offsetting ways. For example, the law lowered statutory tax rates at all income levels, nearly doubled of the size of the standard deduction from $13,000 to $24,000 for a married couple in 2018, and doubled the size of the Child Tax Credit for many families.[29] Yet other provisions raised taxes on families, such as the elimination of personal exemptions and the new, permanent inflation adjustment for key tax parameters.[30] The end result of these offsetting changes is only modest tax cuts overall for most families, which pale in comparison to the law’s large net tax cuts for the wealthy.

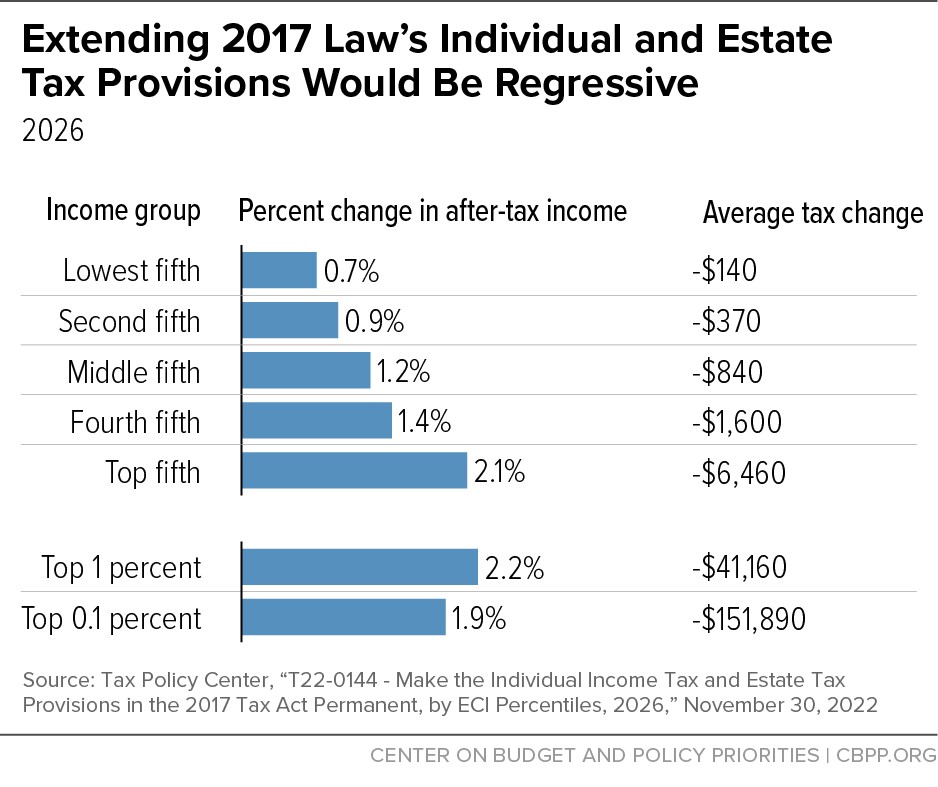

The expiring provisions primarily benefiting affluent households — the cut in the top tax rate, the pass-through deduction, the weakened AMT, and estate tax cuts — account for a majority of the total cost of extending the law’s expiring provisions.[31] Extending the individual income tax and estate tax provisions would boost after-tax incomes for the top 1 percent more than twice as much as for the bottom 60 percent as a percentage of their incomes.[32] (See Figure 3.) In dollar terms, this is a $41,000 annual tax cut for households in the top 1 percent but only about $500 for those in the bottom 60 percent of households, on average.[33] These benefits would be on top of the very large benefits wealthy households receive from the law’s permanent corporate tax cuts.

CBO estimated in 2018 that the 2017 law would cost $1.9 trillion over ten years (not including the cost of interest payments on the debt from resulting larger deficits).[34] Making the individual tax cuts permanent would add another roughly $2.6 trillion in cost from 2024 to 2033, or $300 billion a year beginning in 2027.[35] Making other parts of the law permanent, such as the “expensing” tax break for business investments, which some policymakers have called for, would add hundreds of billions more to this cost.[36]

Footnotes can be found at the bottom of the page at cbpp.org.