A brief introduction by an Econofact News Letter exploring the impact of income on voting turnout. I did not include the explanation link information in this commentary as it would be too lengthy. However, the links are there if you wish to read further into this explanation. This is short enough to provoke a discussion as to why percentages of poorer voters do not turnout for elections. They have much to win in economic progress if the vote for the right candidate. If they do not vote, then they take whatever the other candidate offers. A bit of a rewrite also. See if this makes sense. I think it may . . . Election Day is less than two months away Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2022 Table 7. Reported Voting and

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: politics, US/Global Economics, voter turnout

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

A brief introduction by an Econofact News Letter exploring the impact of income on voting turnout. I did not include the explanation link information in this commentary as it would be too lengthy. However, the links are there if you wish to read further into this explanation. This is short enough to provoke a discussion as to why percentages of poorer voters do not turnout for elections. They have much to win in economic progress if the vote for the right candidate. If they do not vote, then they take whatever the other candidate offers. A bit of a rewrite also.

See if this makes sense. I think it may . . .

Election Day is less than two months away

Voting and Registration in the Election of November 2022

Table 7. Reported Voting and Registration of Family Members, by Age and Family Income: November 2022

Economic conditions have consequences for elections and elections have economic consequences. This Weekend Reading presents memos and podcasts (see below) investigating the economics of voting and elections. Included are how voting patterns differ by income, how local and regional economic conditions influence the outcome of elections, and some of the economic effects of the outcomes of Presidential elections.

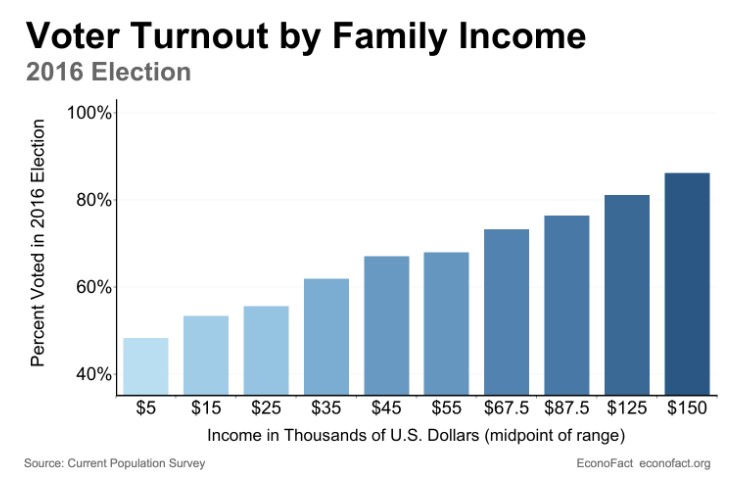

Voter turnout in the United States is vastly unequal across income groups.

Richer people are more likely to vote than poorer people. In the memo Voting and Income, Randall Akee (UCLA) documents the increase in voting participation across income deciles in 2016 (see chart). For example, there was a striking contrast between the 48 percent for people in the lowest decile as compared to the 86 percent rate for those in the highest decile.

A possible reason is that people who are better off are less consumed by day-to-day demands on their time than those who are poorer. Higher incomes may also be linked with a greater sense of civic duty or a greater belief in the benefits of voting. Randall’s research finds that low-income people who experience sudden windfalls in income are not more likely to vote. However, their children are significantly more likely to vote as adults, suggesting that higher incomes can increase civic engagement in the long term.

There is historical evidence that wealthier voters tend to support the Republican party.

But this presents a puzzle because richer states tend to vote for Democrats while poorer states tend to lean Republican. In the EconoFact Chats episode Voting, Income, and the Red-state, Blue-state Paradox, Andrew Gelman (Columbia) resolves the puzzle by noting that state differences are not big among poorer voters. However, the differences are bigger among those who are richer. Democrats prevail among those who are better off in richer states and Republicans prevail for this income group in poorer states. Andrew says, in a somewhat dated reference, “. . . it’s not the Prius versus the pickup-truck, it’s the Prius versus the Hummer.” More recently, Andrew says the income partisan relationship has eroded and broader economic conditions have become more important, with incumbents tending to do worse in a poor economy.

An example of the influence of economic conditions on elections

An example of the influence of economic conditions on elections is the impact of the loss of manufacturing jobs. Economic decline in former manufacturing communities did contribute to the victory of Donald Trump in 2016. Jeffry Frieden (Harvard), J. Lawrence Broz (UC San Diego), and Stephen Weymouth (Georgetown) explain the issue in the memo The Politics of Manufacturing Decline.

Communities in the Industrial Belt were the hardest hit by declining manufacturing employment, resulting in a downward economic spiral as towns lost much of their local tax base and were left with an aging, less educated workforce. Jeff, Lawrence, and Stephen found that the counties with high rates of manufacturing job losses saw bigger swings in votes for Trump in 2016 as compared to votes for Mitt Romney in 2012. These results suggest that anti-globalization rhetoric appeals strongly to people living in distressed industrial regions.

Presidential candidates usually promise to deliver economic prosperity

Presidential candidates usually promise to deliver economic prosperity. However, the views on how to achieve economic prosperity can diverge significantly. The Democratic and Republican nominees for the presidency have each proposed different strategies related to taxation, immigration, international trade, and subsidies. Will their proposed policies foster economic growth, low inflation, a vibrant labor market, and a healthy macroeconomy?

In the EconoFact Chats episode “The Macroeconomics of the Outcome of the Election,” Mark Zandi (Moody’s Analytics) discusses the likely macroeconomics of the outcome of the election through differences in proposed policies such as tariffs, taxation, and support for a clean-energy economy. He also notes that the joint outcomes of the Congressional election and the Presidential election have important implications for the economy.