The U.S. economy has been growing faster than military spending, so defense spending as a share of GDP has been decreasing. While the $dollars spent are increasing, the percentage of GDP Defense Spending takes up has been decreasing since 1952. Perhaps a better question is do we really need to spend this much on Defense? Perhaps wiser and defined expenditures may be in order? U.S. Defense Spending in Historical and International Context Econofact The Issue: The United States Department of Defense has requested nearly 0 billion for fiscal year 2025. This represents about 3% of national income and almost half of all federal discretionary budget outlays. What is this money spent on? While there had been talk in the past of a peace

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Defense, politics, Share of GDP, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

The U.S. economy has been growing faster than military spending, so defense spending as a share of GDP has been decreasing. While the $dollars spent are increasing, the percentage of GDP Defense Spending takes up has been decreasing since 1952. Perhaps a better question is do we really need to spend this much on Defense?

Perhaps wiser and defined expenditures may be in order?

U.S. Defense Spending in Historical and International Context

The Issue:

The United States Department of Defense has requested nearly $850 billion for fiscal year 2025. This represents about 3% of national income and almost half of all federal discretionary budget outlays. What is this money spent on? While there had been talk in the past of a peace dividend with the fall of the Soviet Union, have recent events like the Russian invasion of Ukraine and heightened tensions with China led to higher defense spending? How does United States military spending compare to that of other countries? In particular, how valid are the complaints that the United States bears the burden of defending its allies? Could the burgeoning national debt, and the push towards a more inward-looking foreign policy alter spending priorities?

The Facts:

– Current U.S. military spending is higher than at any point of the Cold War in inflation-adjusted terms, but relatively low as a percent of national income.

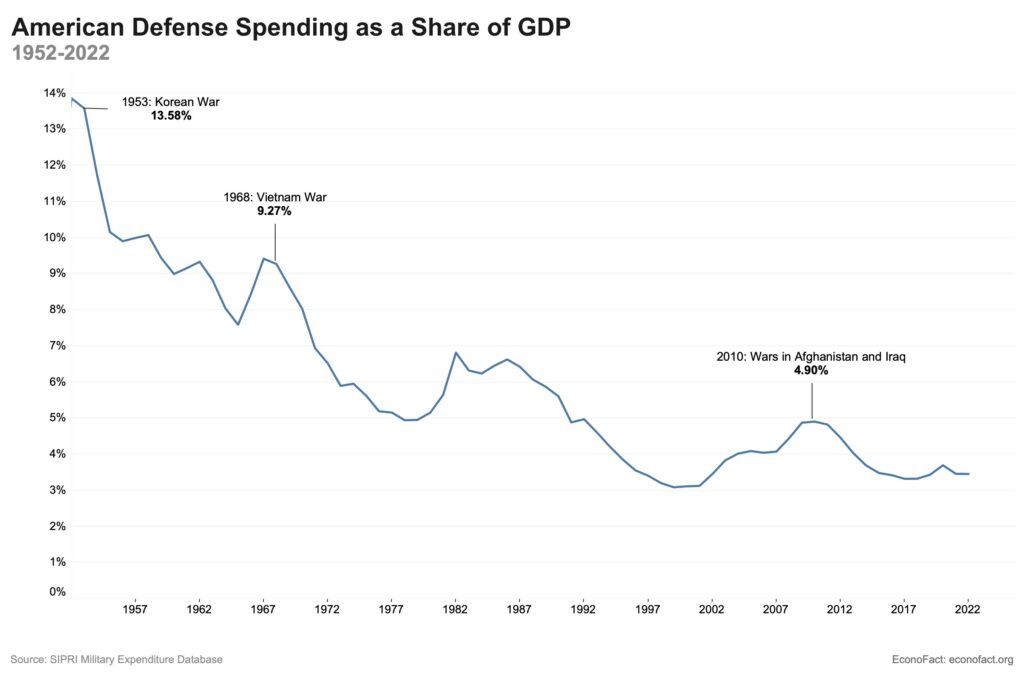

The graph above shows defense spending as a share of GDP. Military spending relative to GDP is arguably a more appropriate gauge of a country’s defense burden than the inflation-adjusted dollar amount, since a bigger economy can support greater spending. The $850 billion earmarked for defense spending in 2025 represents about 3% of GDP. This is a relatively low percentage as compared to the experience of the past three-quarters of a century. The United States economy tends to grow faster than military spending, so defense spending as a share of GDP has been decreasing. In the 1950s, and through the Vietnam era, defense spending was typically 8 to 10% of GDP, about three times higher than current spending relative to the size of the economy. After the Vietnam drawdown, defense spending dropped to around 4.5% of GDP which is almost 50 percent bigger than the current share of national income spent on defense. Defense spending increased to about 6% of GDP during the Reagan Administration while the “peace dividend” brought spending down to roughly 3% of GDP during the Clinton Presidency. The wars in Iraq and Afghanistan during the Bush and Obama administrations saw defense spending rise to about 4% of GDP.

– Personnel costs account for nearly half of all defense spending, while most of the other half goes towards procurement, research, development, and testing.

Budgeted salaries and benefits for the 1.3 million active-duty, and 800,000 reserve uniformed personnel for FY 2025 totals about $182 billion. This reflects the cost of all-volunteer armed forces (as opposed to the cheaper alternative of conscription). In addition, a significant share of the roughly $340 billion operations and maintenance budget will go towards paying the 750,000 full-time civilian employees of the Department of Defense, as well as contractors. Roughly $170 billion is earmarked for procurement, and about $143 billion for research, development, testing, and evaluation.

– While the cost of maintaining an expansive overseas presence often comes under scrutiny, basing the same number of units at home instead would sometimes be more expensive.

The U.S. operates about 750 overseas military facilities, mostly in Europe and East Asia, at a cost of $55 billion in 2021. But basing these units at home instead would sometimes be more expensive. The extra cost arising from transporting troops and materiel to foreign bases and building schools for children of military personnel stationed overseas are sometimes much less than the main expenses representing salaries and the cost of military equipment, and these expenses are very similar regardless of whether they are supporting a domestic or a foreign base. Moreover, host governments often contribute to basing costs. For example, between 2016 and 2019, Japan and South Korea — countries which host 45% of all overseas active-duty U.S. troops — provided $12.6 billion and $5.8 billion of the roughly $34 billion it cost to station troops there.

– The United States accounts for nearly 40% of global military spending. It devotes a larger share of its GDP to defense than most other countries.

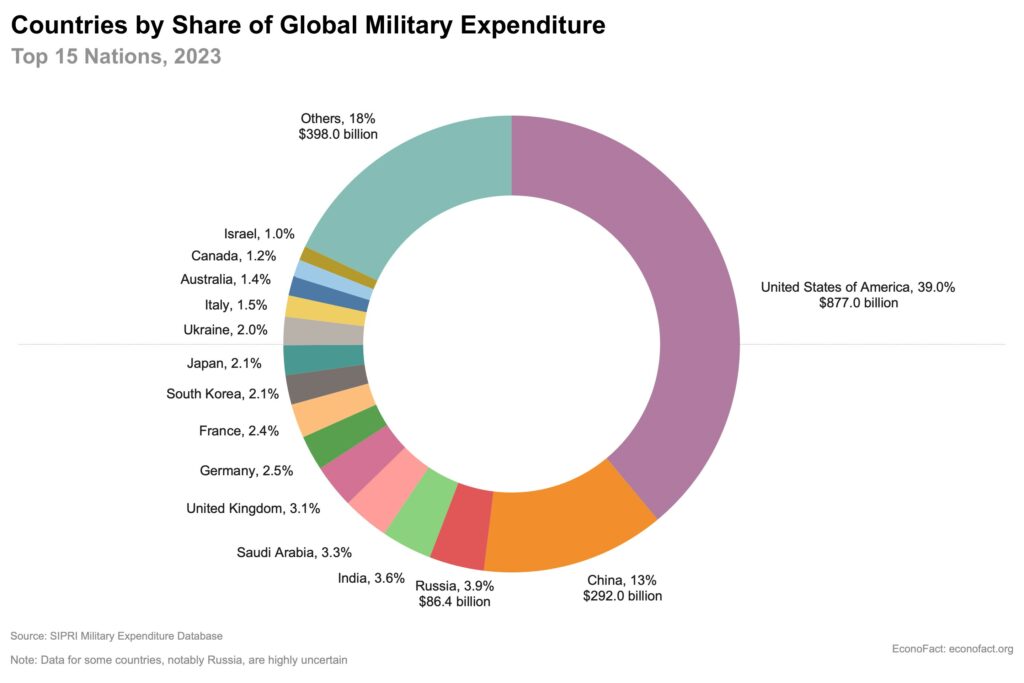

The graph above shows that U.S. military spending was greater than the next ten biggest spenders in 2023. There are some problems in the comparability of these numbers, however, since personnel costs are lower when there is military conscription as opposed to an all-volunteer force, and in lower-income countries. Additionally, the United States purchases weapons from private companies like Lockheed Martin, Raytheon and General Dynamics, rather than having a government arsenal. While defense spending as a share of GDP in 2019 was higher in the United States than in any major industrial country — with only Israel, Jordan, Pakistan, Iraq and Iran devoting more of their national income to defense — similar issues make cross-country comparisons tricky. (Reliable data for North Korea isn’t available, though defense spending is widely believed to be over 10% of its national income. More recently, Russia has ramped up its military spending to an estimated 6% of GDP. China, too, is thought to have increased its military spending in recent years. Its expenditure is still likely a smaller fraction of its GDP than the United States).

What this Means:

Defense spending is a large enough part of the federal budget to have relevant economic implications, and it can be especially important for locales where bases are situated. Defense spending also has a record of fostering research and development of new technologies. But the core reason for these expenditures is, naturally, national defense. While there is debate about the appropriate size of the military budget, I estimate that sustaining this country’s defense strategy would require a one percent real growth rate in the defense budget, although there is unavoidable uncertainty associated with this figure. This is less than the 3 to 5 percent annual real growth in defense spending endorsed by many strategists, but is greater than the likely growth under the Biden-McCarthy agreement of spring 2023 and, as such, is slightly above where the defense budget appears to be headed in the short term.