So they used to tell the story about a guy who claimed he could make cars out of wood, and he started a company in Oregon that brought trees into one door of his giant building with new cars coming out of another door, and he wouldn’t let anyone inside to see how it was done. He was given a award for innovation and widely acclaimed, until one day someone got inside and saw he was shipping the trees out the back to Japan and bringing in new Korean cars. He was then arrested and jailed, etc. etc. Point is, for the macro economy it didn’t make any difference what was going on behind those closed doors, and that for purposes of understanding one can think of foreign trade as a company that takes in all that you export are and delivers back whatever is imported. This model also promotes the understanding of how, in real terms, exports are the costs of imports, and optimizing real terms of trade is about getting the most cars for the fewest trees, which is likewise what productivity is all about for the domestic economy. What about the jobs lost due to increased productivity? Well, history shows it used to take 99% of the workforce to grow the food we need to eat to live, and today in the US it takes maybe 1% of the workforce to grow enough food to eat with a lot left over to export. Yet unemployment isn’t necessarily any higher today than it was back then.

Topics:

WARREN MOSLER considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

So they used to tell the story about a guy who claimed he could make cars out of wood, and he started a company in Oregon that brought trees into one door of his giant building with new cars coming out of another door, and he wouldn’t let anyone inside to see how it was done. He was given a award for innovation and widely acclaimed, until one day someone got inside and saw he was shipping the trees out the back to Japan and bringing in new Korean cars. He was then arrested and jailed, etc. etc.

Point is, for the macro economy it didn’t make any difference what was going on behind those closed doors, and that for purposes of understanding one can think of foreign trade as a company that takes in all that you export are and delivers back whatever is imported.

This model also promotes the understanding of how, in real terms, exports are the costs of imports, and optimizing real terms of trade is about getting the most cars for the fewest trees, which is likewise what productivity is all about for the domestic economy.

What about the jobs lost due to increased productivity? Well, history shows it used to take 99% of the workforce to grow the food we need to eat to live, and today in the US it takes maybe 1% of the workforce to grow enough food to eat with a lot left over to export. Yet unemployment isn’t necessarily any higher today than it was back then. Why? Because there’s always a lot more we think needs to get done than their are people to do it, and unemployment comes from a lack of funding, and not a lack of things to day. Today the service sector dominates, and more so every day, with no lack of services we’d like to have done as far as the eye can see. And unemployment, as currently defined, is necessarily the evidence that for a given level of govt. expenditure the economy is that much over taxed, as a simple point of logic. Not that policy makers understand that, of course…

Now let’s add a border tax to the model, for the purpose of creating jobs, not withstanding how that premise is categorically ridiculous, as per the prior discussion. But, to quote Don Rumsfeld, ‘We’ve got to fight with the army we’ve got.’ Anyway, a border tax would put a tax on importing the cars to attempt to keep us from buying them so we would have more jobs building cars domestically, and reduce the tax on exporting the trees so we would have more jobs cutting down and shipping out trees.

Let’s assume that’s what happened and look at those consequences. First, we would be shipping out more trees and getting fewer cars. This makes the nation as a whole worse of due to those reduced real terms of trade. The next step is to identify the winners and losers, recognizing the losses to our standard of living are higher than the gains. Best case we put more people to work growing more trees so we have just as many trees for ourselves, and we’d put more people to work building cars so we’d have just is many cars as before. So what we accomplished is that we are working more to be left with the same amount for ourselves.

That’s called a drop in productivity, and a decline in our standard of living, as work is an input and a real cost of production. Work itself is not an economic benefit. The economic benefits of work is the output produced. And the whole point of producing output is consumption of some type, either for immediate use or for future use. That is, makes no economic sense to work and produce output for the purpose of immediately throwing it away.

So with the above ‘best case’ assumptions, the border tax does work to create jobs, and unemployment is a political problem, which is why the border tax has that element of political appeal. Not that it matters, but my first choice for job creation would be a fiscal adjustment, either a tax cut or spending increase, large enough to promote sufficient spending to increase sales, output, and employment to produce that additional output. That way we have that much more domestic output to consume plus all the imported cars we were buying before the border tax, and we don’t have to give away the extra trees due to the border tax proposal.

And how does it look from the government’s point of view?

First, the government expects extra revenue from the tax on the imported cars, net of the revenue lost from tax benefits for exporters. This means less spending power for consumers paying the tax, presumably offset by new tax cuts, making it all revenue neutral, which through some presumed channels is theorized to have its own positive consequences.

So in this ‘best case’ scenario Americans work more and get less, while consumer taxes go up while other taxes go down. Hardly seems worth a second look?

But that is only the economic best case scenario. All kinds of other things can happen, with the same model used for purposes of analysis.

More later…

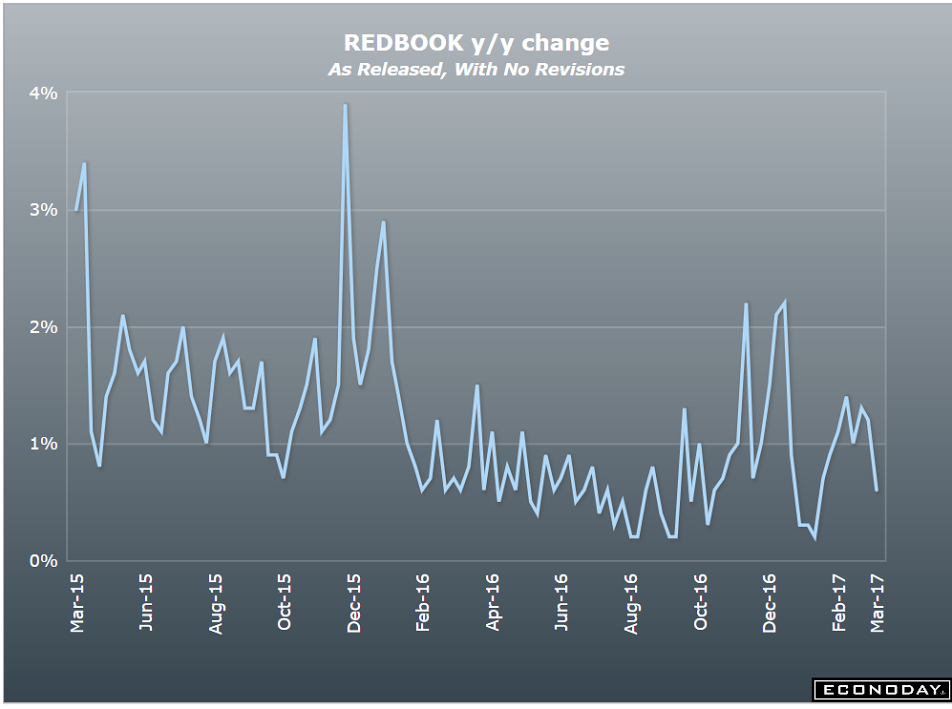

This used to run between 3% and 4% before the collapse In oil capex:

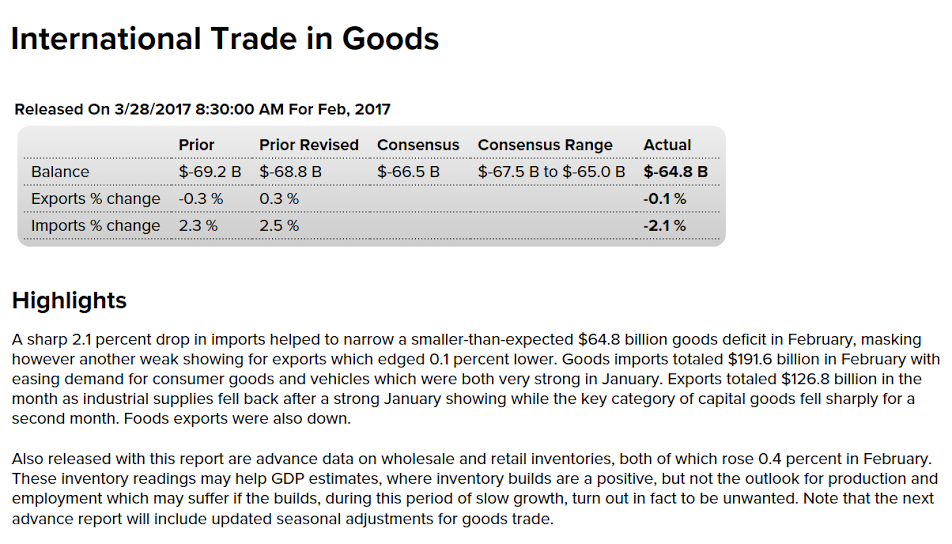

A bit ‘better’ than expected, to use mainstream values, and note the details in the narrative are not so ‘good’:

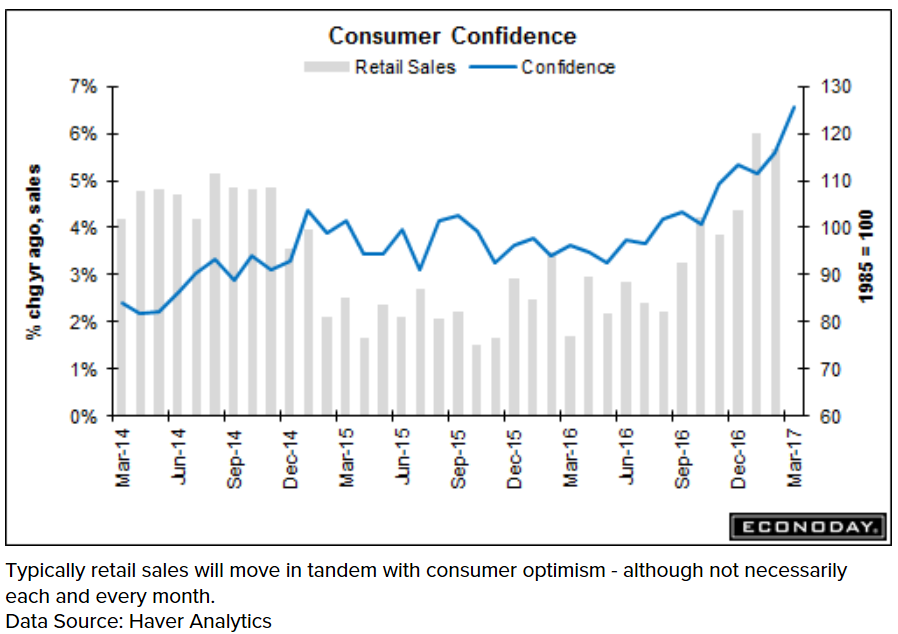

Seriously trumped up consumer expectations continue: