2018 Midterm election economic forecast: a struggling expansion that may amplify a wave We are now one year out from the 2018 midterm elections. Generally speaking, only the more involved voters show up for midterms, which seem to turn mainly on how much voters who “strongly” disapprove of actions in Washington outnumber those who “strongly” approve. Last week I noted that this metric correlated very well with the Virginia results, which featured elevated turnout by strongly approving GOPers, but an even bigger surge by strongly disapproving Democrats. While the economy does not play so important a role as it does in presidential elections, certainly the economy is relevant to “strong” approval vs. disapproval. So let’s take a look at what the economy

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: politics, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

2018 Midterm election economic forecast: a struggling expansion that may amplify a wave

We are now one year out from the 2018 midterm elections. Generally speaking, only the more involved voters show up for midterms, which seem to turn mainly on how much voters who “strongly” disapprove of actions in Washington outnumber those who “strongly” approve. Last week I noted that this metric correlated very well with the Virginia results, which featured elevated turnout by strongly approving GOPers, but an even bigger surge by strongly disapproving Democrats.

While the economy does not play so important a role as it does in presidential elections, certainly the economy is relevant to “strong” approval vs. disapproval.

So let’s take a look at what the economy is likely to look like one year from now when midterm voters cast their ballots. To cut to the chase, if you are a democrat and you were counting on a recession to drive angry voters to the polls, that’s unlikely to happen. But on the other hand, the expansion is likely to be very lackluster, enough so that, if there is going to be a wave anyway, it may be amplified.

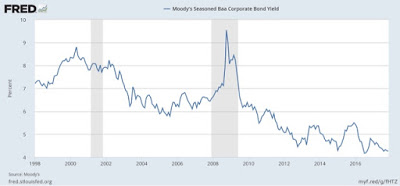

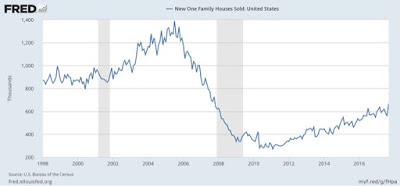

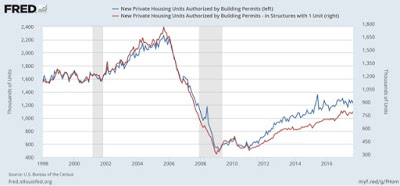

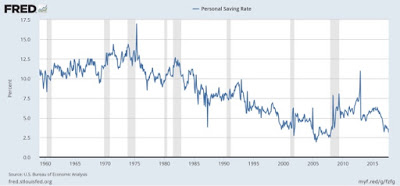

There are generally three sectors of long leading indicators: financial, producer, and consumer. The housing market is uniquely important, and straddles to some extent all three.

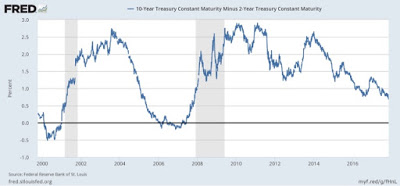

[I still suspect that the yield curve is the indicator most likely to not accurately signal in our deflationary era.]

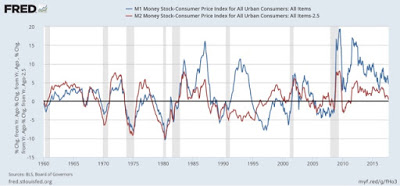

Real M1 is also very positive (blue in the graph below), but it is offset by a neutral real M2 (red):

Housing permits, both for all houses, and for the less volatile single family houses, have not made new highs since last winter:

and real residential fixed investment as a share of GDP has also declined in the last two quarters:

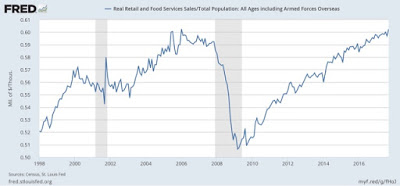

But on the plus side, real retail sales per capita, which has peaked about 12 months before the last several recessions, has continued to improve:

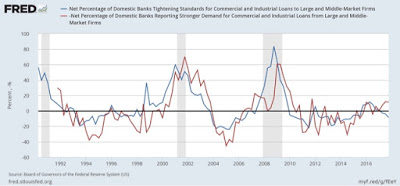

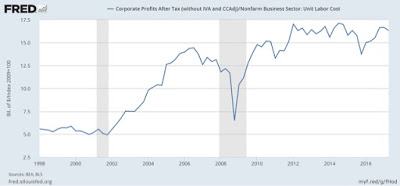

The bullet-point summary of all these indicators is that we have a stretched but still spending consumer, muddling along producers, and wide open financial spigots. Overall these are a weak, but not yet negative, set of metrics.

Barring an outside shock, one year from now when midterm voters cast their ballots, we should expect an economy that is still growing, but more weakly than last week when voters in Virginia and New Jersey swept away GOP candidates. In short, if there is going to be a big wave anyway, the condition of the economy is likely to increase somewhat the intensity of that wave.

From Bonddad —

I agree with NDD’s analysis, although approach it from a slightly different angle. I wrote about it last week in my US Economic Week in Review