The Covid-19 epidemic is creating a painful dilemma for policymakers. On the one hand, we need to practice social distancing to keep people healthy and to prevent our hospitals from being overwhelmed. Unfortunately, this strategy is causing a severe economic contraction as people avoid contact with others. An ideal response to this dilemma would have three basic components. First, we would implement a hard, nation-wide lockdown to slow the spread of Covid-19. This would “flatten the curve” and save lives by preventing hospitals from being inundated with patients in the next few weeks. It would also buy time to put in place the testing, prevention, and surveillance measures we will need to start cautiously re-opening our economy. Putting these

Topics:

Eric Kramer considers the following as important: Featured Stories, Healthcare, Hot Topics, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

The Covid-19 epidemic is creating a painful dilemma for policymakers. On the one hand, we need to practice social distancing to keep people healthy and to prevent our hospitals from being overwhelmed. Unfortunately, this strategy is causing a severe economic contraction as people avoid contact with others.

An ideal response to this dilemma would have three basic components. First, we would implement a hard, nation-wide lockdown to slow the spread of Covid-19. This would “flatten the curve” and save lives by preventing hospitals from being inundated with patients in the next few weeks. It would also buy time to put in place the testing, prevention, and surveillance measures we will need to start cautiously re-opening our economy. Putting these measures in place should be the second element of our strategy. Finally, as Paul Romer and Alan Garber argue, we need a major effort to increase our capacity to test for Covid-19, and to produce masks, gloves, and other forms of personal protective equipment (PPE) by an order of magnitude or more. The ability to do mass testing and to provide masks and other PPE to most Americans will substantially reduce the risk that the epidemic drags on for many months and leads to an economic catastrophe. (For further discussions, see here, here, and here.)

In this essay I explain why it is important to massively increase our ability to produce Covid-19 tests and PPE. I also discuss how this can be done, considering the apparent reluctance of the Trump administration to lead this effort. I make four basic points.

First, the ability to test millions of people daily for Covid-19 and to produce PPE for millions of Americans will require a large up-front capital investment by manufacturers that may turn out to be unneeded, but this investment is socially justified to lessen the risk of a severe and protracted economic shutdown.

Second, without firm contractual commitments from the government, businesses will not invest at the scale required to ensure that we can avoid a disaster. Several factors will deter adequate investment by industry; the most important is probably the risk that the epidemic will abate and they will not be able to recover their investment costs. The government can overcome this problem by agreeing to pay companies for tests and PPE even if the epidemic abates, by subsidizing investment in the capacity to produce tests and PPE, etc. The critical point is that the government needs to make binding commitments NOW, it cannot wait to see if the epidemic can be brought under control using other means. Valuable time has already been lost.

Third, the powers that the President has under the Defense Production Act to directly control the use of resources are not particularly useful if our goal is to spur investment in the capacity to produce tests and PPE. We need to give firms incentives to invest in new capacity using contracts, competitions, and similar tools.

Fourth, an ambitious effort to expand production of tests and PPE will inevitably lead to genuine contracting failures and to situations that create the perception of failure. Trump is clearly anxious to avoid setting ambitious goals and taking actions that might later be used to criticize him. In response, Congressional Democrats want to force Trump to exercise his powers under the Defense Production Act.

This is a mistake. Trump would likely veto any bill that tried to force him to act, and, in any event, it is very difficult for Congress to force a reluctant President to act. Fortunately, there is no need for contracting efforts to be directed by the President. Rather than trying to force a reluctant Trump to exercise his contracting powers under the DPA, Congress should either delegate the power to an agency, or it should create incentives itself, directly. I will sketch out how this can be done. The same point applies to efforts to organize mass testing, the distribution of equipment, and other activities where direct commands are an effective means of achieving our goals: Congress should accept that Trump is unwilling (and arguably unable) to lead these efforts and try to work around him in ways that he can accept.

Mass testing and distribution of PPE mitigate the risk of economic disaster

Social distancing is leading to a rapid collapse of economic activity in the United States and around the world. The economic costs will very likely be manageable if the epidemic is short-lived and people can return to work soon. If the epidemic drags on and social distancing continues, however, the economic destruction could be deep and long-lasting.

How long will the economic “sudden stop” from the epidemic will continue? The honest answer is that we do not know. It is possible that we will bring the epidemic under control with strict social distancing, modestly increased testing, and other public health measures. China appears to have its epidemic under control, which is a hopeful sign. It is possible that we will get a reprieve from warmer weather, if the virus is seasonal. We may even find an effective treatment that will allow most people to resume normal activities.

On the other hand, there is a real possibility that the epidemic will ebb and flow for months. We may not be willing to take the kind of aggressive measures that China used to stop the spread of the coronavirus. Geographically uneven restrictions may allow the virus to move from place to place, reinfecting areas that have successfully contained the epidemic. And even if aggressive restrictions control the epidemic, it is not clear that we can prevent a recurrence of the disease when people emerge from their homes and go back to work. A recent survey found that experts predicted on average a 73% chance of a second wave of the epidemic in 2020. There is even a small possibility that the virus becomes more lethal, causing even greater economic disruption and loss of life.

To minimize the risk of a long-term economic shut-down, we need to act now to increase our capacity to produce Covid-19 tests and PPE in much higher volumes than is currently possible. If we develop the capacity to test millions of people for Covid-19 each day, we can identify and isolate almost everyone who is infected, and we can engage in widespread monitoring to identify emerging hot spots. This will allow people who are not at high risk to resume normal activities, including work and school. The epidemic will end, and the economy can start to function again. Similarly, if we develop the capacity to produce hundreds of millions of masks and other types of protective gear each day, it will be much safer for people to return to work even if the virus is not completely contained. We will not need all of the additional testing or personal protective gear we produce if the epidemic abates, but we will likely use some of it, and the ability to produce mass quantities is a crucial insurance policy against disaster.

It is important not to be misled by the flurry of activity by firms trying to produce more masks and test kits. This activity is important, but no policy currently in place or planned will produce the quantity of tests and PPE we need for mass testing and mass self-protection.

The market will not provide incentives for the required investment in productive capacity

The market will not provide adequate incentives for manufacturers to invest in additional production capacity or in new technologies. Government needs to act.

Companies will not make the investments needed to scale up production without an assurance from the government that they will be compensated for the costs they will incur. For example, to ramp up production of the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) machines that are used to process Covid-19 tests, manufacturers will need to hire new employees and retrain existing employees, sign binding contracts with key suppliers, find new production facilities, purchase capital goods, etc. Without a firm commitment from the government to subsidize investments in capacity or to pay for new PCR machines regardless of whether they turn out to be needed, companies may end up with large losses on unused capacity and unsold machines if the epidemic abates. The same thing may be true even for apparently simpler products like masks. It is one thing for companies to run extra shifts using existing equipment and workers, but if we want to be able to expand production to make masks widely available to the public, companies will need to make large investments in capacity. These investments in capacity will only be needed for a short time and may not be needed at all if the epidemic abates. (I note that N95 masks are not, in fact, simple to manufacture, at least if we want them to meet current standards. Perhaps these standards should be relaxed under current circumstances, although what type of regulation if any should be put in place is unclear.)

In addition to the risk of not recovering investments because the epidemic ends relatively quickly, companies may fear large losses if new treatments or competitive products emerge, or if their competitors also expand production leading to a price war. Some companies may also need government financing, especially small companies or researchers working on new technologies. For all these reasons, private investment without government involvement is likely to be far below what is prudent to mitigate the risk of economic disaster. I illustrate two of the problems noted above with a simple example at the end of this post.

An investment in testing and PPE capacity will help other countries control the pandemic, which is both good in itself and of indirect benefit to the United States, because our economy will continue to suffer as long as the world economy is in lockdown.

Direct allocation, incentives, and the Defense Production Act

The Defense Production Act gives the President two types of powers: powers to direct the use of existing resources and existing productive capacity, and powers to contract with private businesses.

Democrats and some Republicans are understandably frustrated that President Trump has refused to use his powers under the Defense Production Act to redirect existing supplies and current production of masks, ventilators, and other supplies:

Two bills from Senate Democrats would force Trump to use the full power of the DPA to order and distribute medical supplies if they were ultimately enacted.

. . .

Sen. Tammy Baldwin (D-WI)’s legislation would require Trump to prioritize an order of 300 million N95 face masks, 24 hours after it goes into effect. It would also call on FEMA to submit a report about the medical supply needs across the country, no more than one week after the bill has been passed, so there’s comprehensive data about exactly what’s needed.

The Medical Supply Chain Emergency Act from Sens. Chris Murphy (D-CT) and Brian Schatz (D-HI), would also compel the president to use the DPA in order to produce 500 million N95 face masks, 200,000 medical ventilators, and 20 million face shields.

Both bills would require Trump to use the DPA authority. If passed, they would have the legally binding authority to compel Trump to act, though the president would be able to both veto the bills and decline to enforce them, the latter of which could prompt a court challenge. Their additional provisions differ slightly, however.

Baldwin’s, for example, requires FEMA, and the Department of Health and Human Services, to produce a comprehensive review of the key shortages the country is facing when it comes to medical equipment. Murphy and Schatz’s bill, meanwhile, calls on the president to play a more active role in coordinating the distribution of supplies and equipment across states, to ensure that they don’t have to compete against each other for these materials as many are struggling to do now. Theirs would also call on the president to play a role in ensuring supply pricing is “fair and reasonable.”

“The current system, in which states and hospitals are competing against each other for scarce equipment, is both unnecessary and barbaric,” Murphy said in a statement. “It’s time to centralize the critical medical supply chain and distribution during this public health crisis.”

The legislation discussed in the article quoted above seems to be focused primarily on alleviating immediate shortages and preventing price gouging, not expanding production capacity for protective gear and testing capacity for the coronavirus by an order of magnitude or more.

The government has a useful role to play in coordinating the use of existing supplies and directing new production based on existing capacity to the most beneficial uses. There is no reason to think that competition between states or hospitals will end up delivering ventilators or masks to the hospitals that need them the most. Similarly, the government should coordinate surveillance testing, move medical personnel and equipment to areas of greatest need, etc.

When it comes to massively ramping up productive capacity and bringing new technologies on-line, however, the government will need to rely much more on incentives and competition, and much less on its powers to direct the immediate use of resources. There are two basic reasons to focus on incentives and competition. First, the government simply lacks the information about production possibilities at hundreds of different factories to manage this process directly. Even when it comes to scaling up the use of established technologies the government does not have the capacity to manage the large number of firms and complicated supply chains involved. By using incentives and subsidies of various types, the government can engage a wide range of established firms, entrepreneurs, and researchers to contribute to this effort.

Second, many of the companies we will need to participate in this effort are located overseas and cannot be commandeered by the government under the Defense Production Act or some similar scheme. They will need to be induced to participate using carrots, not sticks. When this emergency is over we can debate whether and how to repatriate critical supply chains. But you go to war with the army you have, and right now we rely on highly globalized supply chains.

Overcoming the politics of blame avoidance and the incompetence of Trump’s inner circle

The Trump administration has resisted using the Defense Production Act even to increase the production and improve the distribution of ventilators and personal protective gear, a simple intervention that arguably could save many lives. Some in the Administration may oppose the DPA on ideological grounds. However, my suspicion is that the main concern of the administration – and of Trump himself – is blame avoidance.

Trump’s focus on blame avoidance partly reflects his need for adulation and aversion to criticism, but it is arguably politically shrewd as well. If the epidemic wanes, Trump can declare himself a hero and no one will be interested in examining counterfactuals. (For example, the charge that “President Trump failed to take adequate precautions against the risk that the epidemic would resume in the fall” will not be very effective if the epidemic is under control by June and we have a rapid recovery in the fall.) On the other hand, if the epidemic lasts 6 months, he may get blamed even if his actions helped to mitigate the damage, and taking aggressive action may lead people to hold Trump accountable for whatever damage the epidemic does.

Finally, taking action will also expose Trump to blame for real and imagined contracting failures. A massive effort to scale up production will inevitably lead to both real contracting errors and to the appearance of contracting errors. Contracting errors are inevitable; even well-run private companies make contracting errors all the time. The need for speed and the incompetence of Trump’s inner circle will increase the risk of errors. And even if the government acts perfectly there is a real risk that it will end up paying for supplies that are not needed, or for productive capacity that is never used. In addition, to the extent that contracts impose significant risk on companies, prices paid may seem to be inflated because of the need to compensate owners for possible losses. This will create a perception of contracting errors and leave Trump open to (unjustified) criticism.

Given Trump’s evident reluctance to take forceful action to control the epidemic, how should Congress proceed?

If the Administration is opposed to using the DPA on ideological grounds, an approach based on competition and incentives rather than direct allocation of existing supplies and production might gain their cooperation. If Trump is simply trying to avoid responsibility and blame, however, this will not work. A different approach will be needed.

Congress can try to give Trump responsibility that he does not want, and hope that this creates pressure for him to act effectively or at least allows them to blame him for failing to stop the epidemic. This seems to be what Democrats in Congress are trying to do. However, this approach is unlikely to succeed because 1) Republicans are unlikely to support an approach that Trump opposes, 2) Trump may veto a law that attempts to make him responsible for controlling the epidemic, and 3) Trump can simply refuse to implement a law that he disagrees with.

Instead of trying to give Trump responsibility that he evidently wants to avoid, and that he is unlikely to use competently in any event, Congress should try one of two alternative approaches. First, instead of delegating authority to the President directly, as the Defense Production Act does, Congress can delegate responsibility for expanding testing and PPE availability to an executive branch agency, such as the CDC. This approach would give Trump some ability to deny responsibility if things appear to go wrong, while allowing him to claim credit for any successes. Congress could even put responsibility for contracting in the hands of the Federal Reserve. One advantage of this unorthodox choice is that it would insulate the contracting practice from Trump’s incompetent inner circle.

The second possibility is for Congress to create incentives directly, rather than relying on the President or executive branch actors to do this. I would not recommend this approach in general, but in the case of Trump it may be the best option. Let me sketch what this might look like.

Suppose that we want to sharply increase the number of coronavirus tests that can be performed daily. Congress could offer to pay a high price – say $100 per test – for the first billion tests made available. (A billion tests would be roughly 10 million tests a day for 3 months. This would almost surely be enough to stop the epidemic. I assume that $100 per test far exceeds the fully loaded cost per test under normal supply conditions, but that a high price is needed to get firms to create capacity that will only be used for a few months. If this assumption is wrong – I have seen different estimates of testing costs – just adjust the numbers.) The fact that the high price is available for the first billion tests will give companies an incentive to be quick to market. These payments could be subdivided by industry segment to reduce risk and encourage multiple approaches. For example, some of the money could be designated to pay for tests run on newly produced high-volume PCR machines, some could be designated for tests run on newly produced portable machines, some for non-PCR technologies, some for serological tests, some for mass testing combining multiple swabs (this might earn a higher price per test, not per patient). Prices could also vary with the sensitivity and specificity of tests. The payments could be available for (say) 10 months, or until all the tests are used, whichever comes first. At that point any needed tests would be paid for at the (much lower) market price that would then prevail, given the expansion in capacity.

I do not claim that this is the best approach, or even the best approach that does not require much cooperation from the executive branch. For example, this approach does not provide grants or subsidies to academic research labs and it will not work for cash-constrained entrepreneurs who need cost-plus contracts. But it would almost surely sharply increase the supply of tests and reduce the risk of a full year economic shut down that will do unimaginable economic destruction. A similar program could be set up for N95 masks and other forms of PPE.

Why markets do not create strong incentives for investment in Covid-19 testing and PPE production capacity

Suppose that there are two actors, an industry and the government. The industry might be mask and glove producers or makers of PCR testing equipment.

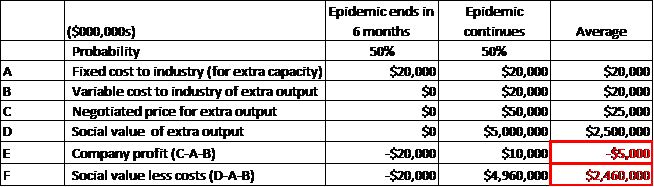

The industry can make an up-front fixed investment of $20 billion dollars to expand its productive capacity. If it makes this investment now, in 6 months it will be able to test 5 million people per day for Covid-19 or produce face masks and gloves for use by the entire population, for an additional, variable cost of $20 billion. The value of tests or masks to society is $0 if the epidemic has abated, and $5 trillion if the epidemic is ongoing. Let us assume that the probability of each of these outcomes is 50%.

Fast-forward six months. If the government has not made a binding commitment to the industry, the government will not pay for the extra tests or masks if the epidemic has ended. In this case, the industry loses its $20 billion investment in expanded capacity. If the epidemic is still ongoing, the government and the industry will negotiate a price for additional tests or masks. Suppose that the price ends up at $50 billion. This will cover the industry’s variable and fixed costs, and leave it with a profit of $10 billion. This sounds like a large return on an initial investment of $20 billion. In fact, the profit seems so large that it may lead to charges of war profiteering. (This illustrates the point I made above about perceptions of contracting failures.)

However, this does not take into account the 50% risk that the epidemic abates and the initial investment is lost. Once we take this risk into account, the expected profit of the industry is a loss of $5 billion. Anticipating this, the industry will not make the $20 billion investment to expand its capacity. This is true even though there are huge social benefits from having the industry invest in the expanded capacity.

To avoid this problem, the government needs to make binding commitments to firms today. For example, it could offer to pay firms for their investment in additional capacity, or it can agree to buy additional output even if the epidemic ends and the output is not needed. This is what the government should do, because the cost of an extended epidemic and economic shut-down is so high. Note, however, that the government needs to do this immediately, before it knows how long the epidemic will last, and there is a real possibility that the government will end up looking foolish after the fact, because it will pay billions for output or investments that end up not being needed.

Finally, industry may not be compensated for its capacity investment even if the epidemic is guaranteed to continue for several months, because bargaining with the government may result in a price that does not cover up front capital costs (bargaining is only guaranteed to cover variable costs). This is an example of what economists call “the hold-up problem”; the standard solution to hold-up problems is to contract in advance.