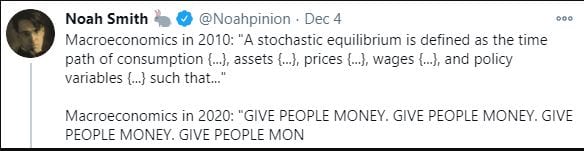

Noah Smith wrote a very interesting post on how macroeconomists are behaving very differently in 2020 than in 2008-9 : The new macro: “Give people money” . He notes two differences : first there is little discussing of theory or of the models used in most peer reviewed articles, second there is (as far as he can tell and he would know more than me) a virtual consensus that we need stimulus and that austerity would be a mistake. Or as a tweet I think this is a vast improvement and demonstrates the success of a wonderful scientific counter revolution. I think it better to read his excellent brief post before reading this long wandering self indulgent post (and maybe best to read his post and not read this post). I trust you have read Noah’s

Topics:

Robert Waldmann considers the following as important: US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

Angry Bear writes The paradox of economic competition

Angry Bear writes USMAC Exempts Certain Items Coming out of Mexico and Canada

Noah Smith wrote a very interesting post on how macroeconomists are behaving very differently in 2020 than in 2008-9 : The new macro: “Give people money” . He notes two differences : first there is little discussing of theory or of the models used in most peer reviewed articles, second there is (as far as he can tell and he would know more than me) a virtual consensus that we need stimulus and that austerity would be a mistake.

Or as a tweet

I think this is a vast improvement and demonstrates the success of a wonderful scientific counter revolution. I think it better to read his excellent brief post before reading this long wandering self indulgent post (and maybe best to read his post and not read this post).

I trust you have read Noah’s post?

He names names. Lucas, Cochrane, Blanchard, Yellen, and Rogoff (it appears to go without saying that Krugman, DeLong and Summers are DSGE skeptic stimulators and that Woodford is a stimulator who actually likes DSGE models (there is no accounting for taste)).

I think the first two names are key — Lucas, Cochrane and, more generally, the Minnesota Chicago fresh water school. As far as Noah knows, they have not had much to say. I think this is key also to the lack of discussion of theory by the economists who have written a lot

Brad Delong’s way to understand the whole DSGE macro episode is that it was all a response to the argument that Keynesian policy recommendations depended on the assumption that people were irrational. The whole decades long episode was an effort to reconcile the Keynesian equations (now considered stylized facts not theory) with Nash equilibrium. It is true (as he explicitly said) that leading New Keynesian Olivier Blanchard, thought of the effect of something important which was not in the model (like covid) using IS-LM-Phillips, translated the is night to DSGE then explained the result with IS-LM-Phillips. He never explained why he did not cut out the middleman and then he cut out the middle man.

Noah Smiths explanation of the existence of DSGE macro is that, during the great moderation, there was not much for macroeconomists to do so they passed the time with DSGE (he also wrote that there wasn’t much for particle physicists to do while waiting for the super colliding super conductor to be built so they passed the time with string theory).

I think both are partly right. Their shared point is that there was not point – no anomaly which could not be fit with old Keynesian models, no gain in forecasting performance or plausible reliability of policy evaluation. I think that when the Lucas supply function was long forgotten (or more exactly adopted as the New Keynesian sticky price based Phillips curve) and Real Business Cycle theory abandoned, it was hard to admit that the whole point of a huge research effort was to refute arguments which never made any sense to non economists and also to solve problems which are hard but not too hard.

In 2008 , academic macro continued – the financial crisis brought attention to many interesting issues which had been set aside. But even then, economists contribution to the policy debate did not rely on DSGE analysis. I think it is even more absent now, because even fewer people are arguing that the market outcome must be optimal (so there is no need to grant almost everyting for the sake of argument when showing that their conclusions do not follow from standard models) and because macroeconomists have been busy discussing real world problems for a decade, and aren’t determined to make things difficult by making strong assumptions which can only be reconciled with reality with great effort.

Smith notes that Lucas misunderstood the implication of standard macro models for the effects of temporary government spending increases on aggregate demand. The arguments for austerity were much more at variance with the implications of standard macro models than were the arguments for stimulus. I do not defend DSGE, but it wasn’t to blame for the shift to austerity. I’d say it worked about as well as it ever had (which is not well at all) once macroeconomists considered financial frictions (as Bernanke and Gertler had for decades) and the (roughly zero) lower bounds on nominal interest rates and wage inflation. I can think of two ways in which DSGE continued to lead people astray after 2008.

One is the expected inflation imp. GE stresses expectations including current expectations about the distant future. Economists were tempted to discuss managing inflation expectations assuming that they could be managed using the magic word “credible”. However, for almost all macroeconomists, this was not presented as a preferable alternative to fiscal stimulus but rather as something that could be done in spite of the attachment of fiscal authorities to austerity.

Another is the assumption that there is one and only one balanced growth path and the economy will return to it fairly soon. This is an assumption made for convenience. It is used to make numerical simulations feasible. It was based on a division of macro into growth theory and business cycle theory. Also it worked OK for the USA (and only the USA) which was the almost exclusive focus of macroeconomic analysis (also when models were then applied to other countries)). This is important, because it implied that interest rates couldn’t remain much lower than they had been 1980-2000 (and couldn’t be much higher 1980-2000 than they had been before). This assumed that there couldn’t be secular stagnation and that the public sector inter-temporal budget constraint must be binding. There was a consensus among macroeconomists about the long run exactly because the focus was on the cycle (and also because it is hard to test long run forecasts with short time series). I think the gradually developing perception that this is the new normal which is not at all like the old normal is important.

One question is why Covid 19 hasn’t lead to as much new theory as the great recession. I think the reason is that the effects are relatively easy to reconcile with the assumption of rationality (so no challemge) and especially because we are still assuming it won’t happen again. Similarly there wasn’t a lot of theoretical work devoted to explaining why economies behaved differently during World War II than they had before or have since.

I think this is another reason why there has been much broader support for stimulus. It is clear we are in an extraordinary situation which we hope will be ended fairly soon using vaccines and which we hope not to ever be in again. It is easier to believe that temporary spending will be temporary. It is easy to argue that deficits of a few trillion each year will add a few trillions to the debt and will not continue. Notably, there wasn’t that much opposition to deficit spending during the World Wars either.

OK now I am about to get rude(r). I think another key difference is that there is currently a Republican in the White House. It is clear that GOP attitudes towards deficits are totally different depending on the party of the President. I think it is also clear that there are economists (no (other) names but I am not thinking of ultra hacks like Kudlow , Moore, Hasset, Laffer, and Navarro) who follow their party.

But mainly Noah wrote a much better post and I hope you read it.