The Road to SerfRanddom I have always enjoyed chapter 10 of Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom — “Why the worst get on top.” Always referring to the last quarter century or so since I first read it. Hayek’s argument struck me immediately as watertight but I was puzzled that he seemed to exempt his own preferred collective from his argument. Maybe he just wanted to slip it past the unwary? Individuals may be individuals but individualists are a collective. Harold Rosenberg coined a fine phrase for such collectives: “the herd of independent minds.” Whether we call it capitalism or free enterprise, the individualist’s Utopia meets Hayek’s definition of collectivism: “The ‘social goal,’ or ‘common purpose,’ for which society is to be organized is

Topics:

Sandwichman considers the following as important: Ayn Rand, Friedrich Hayek, politics, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

The Road to SerfRanddom

I have always enjoyed chapter 10 of Friedrich Hayek’s Road to Serfdom — “Why the worst get on top.” Always referring to the last quarter century or so since I first read it. Hayek’s argument struck me immediately as watertight but I was puzzled that he seemed to exempt his own preferred collective from his argument. Maybe he just wanted to slip it past the unwary?

Individuals may be individuals but individualists are a collective. Harold Rosenberg coined a fine phrase for such collectives: “the herd of independent minds.” Whether we call it capitalism or free enterprise, the individualist’s Utopia meets Hayek’s definition of collectivism: “The ‘social goal,’ or ‘common purpose,’ for which society is to be organized is usually vaguely described as the ‘common good,’ the ‘general welfare,’ or the ‘general interest.'”

We can be less vague in describing the social goal of capitalist society: the accumulation of capital. Does that goal not seem collectivist enough? O.K., then let’s be vaguer and call it economic growth. That way, the people on top can claim to be pursuing the general welfare by promoting the accumulation of capital. Capitalism is collectivist.

Why does organizing society for a common social goal favour the worst? In the first place, success is not guaranteed. When democratic leaders run into obstacles in achieving the plan, they face a choice of giving up or of assuming extraordinary powers. When a dictator faces that choice, the choice is between “disregard of ordinary morals or failure.” That is why “the unscrupulous and uninhibited are likely to be more successful in a society tending toward totalitarianism.” Sound familiar?

How do these unscrupulous and uninhibited people manage to rise to the top? Hayek gave three reasons why a “numerous and strong group with fairly homogenous views,” large enough to impose its views on society, “is not likely to be formed from the best but rather by the worst elements of any society”:

- “the lowest common denominator [of moral and intellectual standards] unites the largest number of people.”

- “those whose whose vague and imperfectly formed ideas are easily swayed and whose passions and emotions are readily aroused… will swell the ranks…”

- “it is easier for people to agree on a negative program — on the hatred of an enemy or envy of those better off [or of those worse off!] — than on any positive task.”

Sound familiar?

What brings me to Hayek is Immanuel Kant, “the most evil man in mankind’s history.” Hayek’s epistemology was neo-Kantian. One might think that the extreme contradiction between Ayn Rand and Fred Hayek, the two libertarian icons, would lead to some kind of open rupture. But no. Even evangelical anti-abortionists have no problem embracing sound bites from the pro-abortion, atheist Rand when it helps them attack the critical race theory enemy. They just let icons be icons.

Do you think First Liberty Institute would mind that their anti-Kant rant echoes a 1960 Ayn Rand lecture titled “Faith and Force: The Destroyers of the Modern World?” I asked them. I’ll let you know if they reply. Here’s the view of a religious group from the other side of the spectrum:

There’s always the danger that watching all the Ayn Rand interviews and reading the lectures and newsletter articles from the 1960s will turn me into an objectivist. But not really. I am amused and mildly charmed by her chutzpah but I cannot be seduced by her borscht-circuit philosophy. Rand inverted Leninism to construct a myth where everyman is free to be Lenin, independent of the Party or the State (but not of the cult and its omniscient creator, Ayn Rand).

In practice, the objectivist is no different from what Rosenberg called “the heroes of Marxist science.” One can paraphrase Rosenberg’s description, simply substituting the word “Objectivist” for “Communist”: “The Objectivist belongs to an elite of the knowing. Thus he is an intellectual. But since all truth has been automatically bestowed upon him by his adherence to Objectivism, he is an intellectual who need not think.”

The backstory on Ayn Rand is that she got the meat of her “philosophy” from New York Herald Tribune columnist, Isabel Paterson, whom she met in 1940 during the Wendell Willkie campaign. Rand was enthralled by Paterson’s erudition. For the next eight years, I.M.P., as she signed her columns, became her mentor. Rand was not well-read; Paterson was a bookworm. Rand sat at Pat’s feet and imbibed the individualist creed.

Paterson was a remarkable woman. She set a flight altitude world record for women less than a decade after the Wright brothers flew at Kitty Hawk. After two years of formal schooling, she became a nationally-syndicated reviewer of books. She wrote several novels and a philosophical/political/economic manifesto on individualism. With a few elaborations and vulgarizations, Paterson’s manifesto, The God of the Machine, was canonized as Rand’s philosophy.

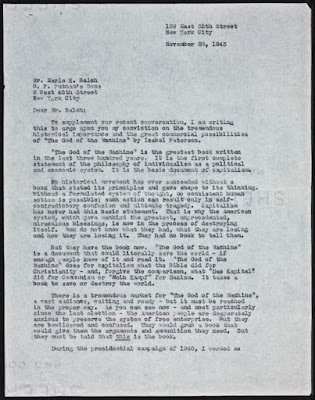

In November 1943, Rand wrote a four-page letter to Paterson’s publisher, G.P. Putnam, urging publicity for the book on the grounds that it was, “a document that could literally save the world–if enough people knew of it and read it.”

“The God of the Machine,” Rand wrote, “is the greatest book written in the last three hundred years. It is the first complete statement of the philosophy of individualism as a political and economic system. It is the basic document of capitalism.” This was high praise indeed, considering Rand’s novel, The Fountainhead, had been published earlier that year.

Kidding aside, was the book really that great? Would it do for capitalism, “what the Bible did for Christianity—and, forgive the comparison, what Das Kapital did for Communism or Mein Kampf for Nazism”? Admittedly, Paterson was a forceful, compelling writer with an impressive breadth of knowledge. Less impressive is the shallowness of her comprehension of the argument of her main ideological adversary, Karl Marx.

Paterson’s argument against Marx was mostly ad hominem: “Marx was a fool with a large vocabulary of long words.” “A parasitical pedant, shiftless and dishonest.” He had “an unacknowledged need to adopt the non-sensical ‘dialectic’ of Hegel.”

“Marx’s theory of class war is utter nonsense by its own definition…” Again, “Marx was a fool…” He had a “superficial mind…”

Beyond the onslaught of disdain are only repeated claims about Marx’s theory being deterministic and mechanistic: …the most grinding despotism ever known resulted at once from the “experiment” of Marxist communism, which could posit nothing but a mechanistic process for its validation.

…they assume that a productive society, which depends primarily on exact communication, can be organized after they have destroyed that means. In this they revert below savagery, and even below the animal level. They have got down to the premise of mere mechanism. Cogs in a machine need no language.

What was Paterson’s rational and individualistic alternative to this deterministic, mechanistic dishonest foolish sub-human non-sense? Society is a machine!

No, seriously. Society is literally a machine:

Personal liberty is the pre-condition of the release of energy. Private property is the inductor which initiates the flow. Real money is the transmission line; and the payment of debts comprises half the circuit. An empire is merely a long circuit energy-system. The possibility of a short circuit, ensuing leakage and breakdown or explosion, occurs in the hook-up of political organization to the productive processes. This is not a figure of speech or analogy, but a specific physical description of what happens.

In spite of Paterson’s insistence that her metaphor is not a figure of speech, it is the central metaphor of her book, as indicated by the book’s title. Any discrepancy in the “hook-up” between the political system and the production process can result in a “short circuit, ensuing leakage and breakdown or explosion.” The examples Paterson gives of such mismatched hook-ups are between European society and the industrial revolution and Native Americans and the introduction of firearms to their hunting economy.

In her weekly column, “Turns With a Bookworm” of July 16, 1939, Paterson laid out the premise of her future book in the form of a report on a conversation with the Irish poet and literary critic, Mary Colum, which concluded with Colum asking Paterson, “Well, why don’t you write that?”

And so she did. Remarkably, Paterson’s grasp of Marx in the resulting book didn’t exceed the reach of an off-hand comment made by Colum one summer evening in 1939.

Somehow the suggestion Paterson once had a job proofreading Capital — “Good grief, didn’t we have to proofread Capital once; and a dreary job it was” — sounds far fetched, or at least apocryphal. Charles Kerr published a revised edition of volume 1 in 1905, volume 2 in 1907 and volume 3 in 1909. Paterson left home for Calgary in her teens and held various jobs for several years. From 1905 to 1910, starting when she was 19, Paterson was employed by a Calgary, Alberta law firm.

About half-way through “The dynamic economy of the future,” the final chapter of her book, Paterson calls attention to “[t]he one problem which may be said to have arisen from the dynamic economy”: the labor problem — “when industry slows down, the workingmen are most visibly affected.”

Paterson offered a partial solution:

There is absolutely no solution for this except individual land ownership by the great majority, and the use of real money. It is not necessary that everyone should own a farm; but enough people must own their homes and have a reserve for “hard times.”

In two sentences, “the great majority” dwindles down to a vague “enough people.” Paterson doesn’t elaborate on how this condition of home ownership and a financial reserve is to be met. Presumably, it can only be achieved by hard work and thrift. Since those “most visibly affected” are most also likely to not have such a reserve, it is hard to see in what way this is meant as a “solution” to the labor problem any more than “stop eating avocado toast” is a solution to the high price of housing.

“It is not necessary that everyone should own a farm…” is a remarkably insensitive statement to make in the aftermath of the great depression when farmers were on the front lines of dispossession. In the wake of the World War I wartime boom, small farms limped through the 1920s faced with low prices, over-supplied markets and rising debt. When “hard times” suddenly went viral after the stock market crash of 1929, many farmers had no reserve because they had already suffered through a decade of “hard times.”

Admittedly, Marx didn’t offer a practical solution to the labor problem, either. What he did, though, is present an analysis of how the accumulation of capital necessarily generates hard times both through cyclical depressions and chronic unemployment.

Although Paterson had a great deal to say about how stupid and dishonest Marx was, she didn’t offer a single sentence about why he was wrong about, for example, “the disposable industrial reserve army of the unemployed” or “the law of the tendency of the rate of profit to decline.” She did, however, offer this chestnut: “The collectivist, with the theory of “technological unemployment,” assumes a fixed number of jobs, another arbitrary quantity.” The lump of labor fallacy!

Backing up to her previous paragraph, this is how Paterson presented the alleged fallacy:

Anyhow, the collectivists were forced to admit that production had refuted Malthus, increasing prodigiously, year by year. Then they had to say that the trouble was “overproduction”; the workingman would work himself out of a job pretty soon! This theory has evoked the phrase “technological unemployment,” which is said to be caused by mechanical improvements in the means of production. That is, if a machine is invented by which one man can do the work previously done by ten men, it must put nine men permanently out of employment. It sounds plausible, but is it true?

Not only is it not true, it is not Marx’s argument, which presumably is what is meant by “the collectivists’ theory.” Marx’s argument is that capital must constantly employ more labor power because labor power is what produces surplus labor. If capital gets rid of nine workers in one factory, it has to hire ten or eleven somewhere else in the economy to up the accumulation process.

Marx’s theory has nothing to do with a “fixed amount of work.” It has to do with disequilibria between supply and demand for commodities — including labor power — that is not adjusted automatically by investment, interest rates or some market deity’s “invisible hand.” Far from assuming a fixed amount of work, Marx argues that the accumulation of capital requires a perpetual increase in the amount of labor employed alongside an increase in unemployment.

Maybe Marx was wrong. If so, a hoary straw man argument demonstrates no such thing. How hoary? The bogus fallacy claim was 163 years old in 1943.It seems possible to me that Isabel Paterson was working out some complex personal issues when she wrote The God of the Machine. According to her biographer, Stephen Cox, she hated her father, whom she saw as a ne’er-do-well and loved her mother who seemed able to get things done even when there was little to work with. She had a poor opinion of many men she knew, who she viewed as weak and feckless.

She was able to “make it” in a patriarchal society pretty much on her own terms. Or perhaps not.

On a visit to Manitoulin Island in Ontario, where she was born, she mentioned that she had “ten thousand cousins” there that she didn’t want to have anything to do with. Ten thousand is an obvious exaggeration. Manitoulin Island has seven Indian Reserves. Paterson was born in the township of Tehkummah about 10 kilometers from what is now called the Unceded Territory of the Wiikwemkoong.

When Paterson was a year old, her family’s house burned down and her family moved to Michigan, then to Utah, and finally to Alberta, next door to the Blackfoot territory. Indigenous characters feature peripherally in several of her novels and are central to her mismatched “hook-up” theory of political organization and production. I didn’t know any of the foregoing when I first saw her photograph and wondered if she was part Indigenous. From the 1920s to the 1940s, assimilationist themes were rife among (acknowledged) Native American authors. What better way to assimilate than to simply become that to which one is assimilating?