In this series we explore marketing farm fresh goods in the litany of different ways as a direct consumer edibles farmer. Many types of farms exist within the framework of directly edible, from market gardens, to 100 acre California avocado fields, dairy barns, hen houses, and multiple large monocrop “people food” producers. Direct to Consumer is exactly what it implies. A farmer seeds, grows, reaps or milks, slaughters and packs food and then sells directly to consumers from the farm or through a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) share program by way of either box delivery to the patrons door steps, a predefined location pickup at a specific time and date, or at the farm gate directly. The closer to the farm is the more advantageous to the

Topics:

Michael Smith considers the following as important: agriculture, Featured Stories, Michael Smith, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

Angry Bear writes The paradox of economic competition

In this series we explore marketing farm fresh goods in the litany of different ways as a direct consumer edibles farmer. Many types of farms exist within the framework of directly edible, from market gardens, to 100 acre California avocado fields, dairy barns, hen houses, and multiple large monocrop “people food” producers.

Direct to Consumer is exactly what it implies. A farmer seeds, grows, reaps or milks, slaughters and packs food and then sells directly to consumers from the farm or through a Community Supported Agriculture (CSA) share program by way of either box delivery to the patrons door steps, a predefined location pickup at a specific time and date, or at the farm gate directly. The closer to the farm is the more advantageous to the farmer, yet the smaller the ability to grow a market. The further from the farm, the larger the market and potential income stream, but the more time and effort committed to logistics and marketing. The legalities of each type of product and marketing also are vastly different, effecting income differently by each product type. It is incumbent upon the farmer to learn and absorb the costs and requirements.

The more complex the level of consumer interaction becomes, the farming will become secondary to the marketing efforts. It is actually advised to start with a farmers market to establish the farm and have a local market that takes care of the entry level marketing for the farmer. Farmers markets have their own issues and will be discussed in part two of this series. Anyone who chooses to go direct to consumer must not only have proficiency in producing abundant croppage, must also be adept at marketing and offering things that the clients or subscribers will choose the farmer over the retail grocer. This dance is crucial and the balancing act very time consuming. Inefficiencies in one of the three pillars will leave the entire model to be hobbled in disarray. Too much time spent overcoming a pest issue while growing organically, will take away from marketing and social networking. Not allowing for derivatives and value add bonuses will leave the clients or subscribers looking back at the retail grocer who is likely to be not only cheaper, but also completes their purchase encompassing consumer goods such as sanitary products, soaps, packaged dry goods, home products and more importantly, quick meals. As the amount of time producing derivatives, packaging, washing and packing, delivering and marketing increases, the less amount of time a farmer will have doing actual farm work, making the closer to the farm market, albeit smaller, more palatable for some, generate less profits, and zero or negative net income. Doorstep and last mile delivery is time consuming but can warrant greater revenues. Those who venture into direct to consumer will struggle, greatly, either way.

From farm gate, highway-side pop up markets or direct to front door delivery services, here are the current three direct to consumer sales models that exist, with varying complexity, pit falls and costs. We will not focus on farmers markets in this part as the farmers markets are their own unique point of sale.

Farm Store

The farm store is the easiest way to market your products, to your neighbors. Simplistically, a farmer can setup a tent, or roll a trailer of fresh watermelon to the county road right outside their gate. As the passers by notice, they stop. The farmer can be present in the transaction or not. In the case of Jim’s dairy barn, Jim is not present and relies on the good faith system where you walk into his establishment, pull milk from his cooler, and a bank bag is on the counter with a bit of change and a sheet of paper for the consumer to let Jim know what you took from the cooler. The money is secondary. Actually the money aspect is tertiary. There are a couple of cameras in Jim’s farm store and are mostly focused on the cooler to make sure the doors are shut and the other is on the piano behind the cash bag counter. Mrs. R loves to listen to random people tinkle the ivories on the old Kimball that is still somewhat in tune. Outside, the heifers will come to the fence outside of the milking barn to say hello and ask for entrance. The calves and human kids alike have a majestic parlay of understanding in the bottle calf barn next door.

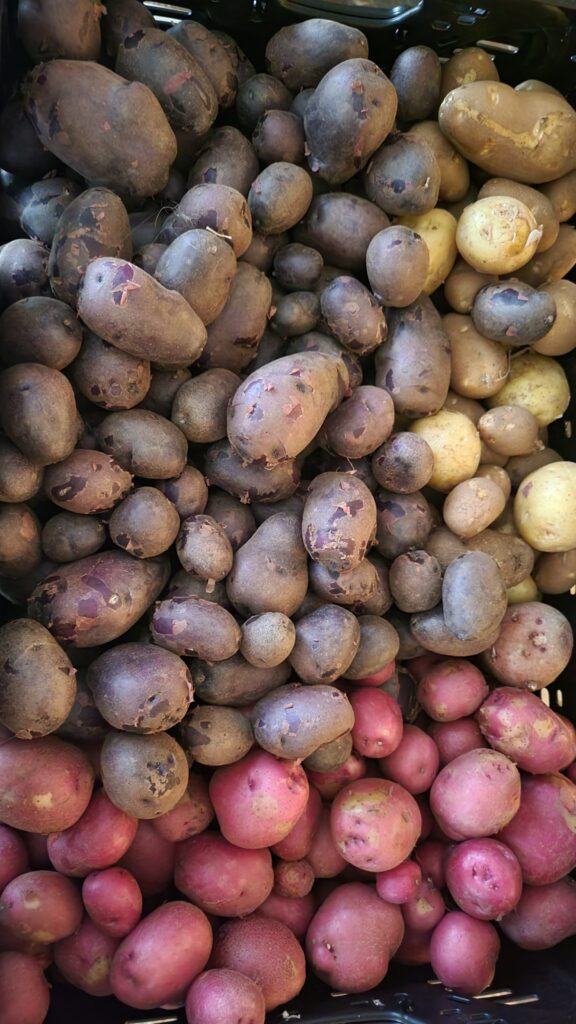

It is a magical place, miles down an empty road, past a defunct racing stable, even further from the sorghum fields and around the corner from the hayfields that Jim reaps for the dairy to sustain through winter. Further down the empty county road patrons realize the dairy barn is deep off the highway of a small town, in a small county over an hour from a major city. Mrs. R only gets to enjoy the locals playing the piano as a usually rare visit when the community has the time and funds to patronize the establishment. The milk is higher in price than what the DFA can supply to the retailers in town. Some crops the same. Watermelon and tomatoes on par with the big grocery stores, but not enough traffic to even move a third of a trailer load. Potatoes, even at the same cost or below, the traffic will not be enough to be close to break even, even with an ad buy from Facebook or Google.

Direct to farm gate is easy. But not profitable.

Roadside Trailer

For many years we have always seen along the highways people with trailers of watermelon selling on the Texas highways, or sweet corn out of the back of a truck in Nebraska.The major difference between the farm gate and the highway trailer is that the farmer has to not only move their produce to a major roadside, but also stay present.This is the main difference between direct from a farm store to active sales. There has to be a concerted effort to load up the whatever it is, and account for its need to be kept cold, frozen, or none of the above, and prepare for that for each crop, protein or product. This can be in the form of nothing for watermelons, ice baths for herbs, eggs, and dairy, or freezers on generators for meat. This increases the costs considerably.The farmer also must consider the licensing and other regulatory requirements that without proper consideration could lead to shutdown of the operation or even fines. The farmer could also potentially be trespassing. The complexities of level two marketing are offset by the marginally increased traffic, yet the time spent off the farm and the likelihood of passers by stopping is highly variable. A pop up market can be profitable, but the social media following has to exist first. Where people can find you is highly dependent on how many followers you have and also how much you are willing to pay to advertise. The algorithms are not built for free publicity once declared a “business”. Aside from social media, a simple market on a heavily traveled road can convey exponential sales that the gate would not have elicited.

Last Mile: To You

This is the most complicated and where I see young and beginning farmers chasing the elusive holy grail; the Blue Apron or Hello Fresh direct to consumer model.

Blue Apron and Hello Fresh are box delivery meal kits. Not farmer CSA boxes. They have the benefit of prepackaged weighted and measured ingredients with recipe cards with almost all ingredients included in the box for a variety of dishes. The costs are very high in relation to locally sourced groceries, but the consumer has to put in the time to develope a recipe and also portion the ingredients with “conventional” meal prep. Meal delivery kits are also subject to cheap produce supply chains from wholesale market goods in the same vein as retail grocers. They are also dependent upon the socialized governmental entity, the US Postal Service for prompt delivery to be in cold storage compliance and food safety regulations. FedEx or other delivery services could also be used, but at a much higher cost. Dissolve the outsourced taxpayer underwritten delivery service and the wholesale supply chains already deployed by wholesale operators and retailers and those meal prep services are nothing more than packaging packers. They take product that has already been packed by wholesalers and pack it again based on recipe cards. Sure they have fancy websites. But what they do also have that farmers do not is venture capitalists, stock markets, angel investors, and massive marketing and advertising firms. It’s also a fad targeting the niche market of urbanites of the middle class realm that work a standard 8-5 and have the time, equipment, and wherewithal to cook said meal kit. Fad, as in, the waning stock and valuation prices for some of these companies has taken a hit recently as inflation worse continue.

Farmers choosing to do last mile deliveries must become wizards of logistics and packaging. Investing in coolers, ice machines, packaging systems, canning, etc. is a large up front cost enterprise, while siphoning off time spent in the fields. Hiring someone to handle the front end logistics and packing could cost anywhere from $25-40,000 a year depending upon commitment. The farm must not only be profitable, but also be able to pay a salary for an additional resource. Even a married couple with two kids working alongside the parents will struggle to keep up with two acres of produce and pastured poultry sufficient to supply a direct to door program.The largest risk is that direct to door assumes the consumer will continue to subscribe to the model, and still be required to seek out goods like hygiene products from major retailers. During a recession, niche services such as box programs tend to wane quickly as households change their expenditures. The quote unquote cheaper option will always win out and the larger retailers have more tools at their disposal to position themselves to promote foot traffic by way of taking losses to generate derivative revenue.

Farms can rarely discount their poultry prices in order to generate enough revenue from meal sides and other products to stop gap the loss of the primary draw of the foot traffic into the retailers’ stores. This is big business versus the little guy or gal, after all. Choose your direct path wisely, friends.