I have known of Lloyd for over a decade and have read his commentary a number of times when he was writing at Treehugger. A parting of the ways came about for Lloyd and other Treehugger writers. Lloyd has his own substack and is presenting his views on recycling, conservation of resources, etc. It is a good read. Lloyd discusses the shift of responsibility for product, packaging, use, and delivery from industry to consumers. Has recycling failed? No, it has been successful beyond the convenience-industrial complex’s wildest dreams, Carbon Upfront, Lloyd Alter August 2023 The purpose of recycling was to make the world safe for single-use packaging. It worked. A recently published study, Recycling bias and reduction neglect, has generated

Topics:

Angry Bear considers the following as important: Carbon Upfront, climate change, Education, Lloyd Alter, politics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

I have known of Lloyd for over a decade and have read his commentary a number of times when he was writing at Treehugger. A parting of the ways came about for Lloyd and other Treehugger writers. Lloyd has his own substack and is presenting his views on recycling, conservation of resources, etc. It is a good read.

Lloyd discusses the shift of responsibility for product, packaging, use, and delivery from industry to consumers.

Has recycling failed? No, it has been successful beyond the convenience-industrial complex’s wildest dreams, Carbon Upfront, Lloyd Alter August 2023

The purpose of recycling was to make the world safe for single-use packaging. It worked.

A recently published study, Recycling bias and reduction neglect, has generated headlines such as Scientists say recycling has backfired spectacularly. This is getting it exactly wrong; the fact that our kids are playing with Rocky’s recycling truck and the world is awash in empty water bottles and Timmy’s or Starbucks’ coffee cups is proof that the concept of recycling has been a spectacular success for the people who invented it: the single-use packaging and petrochemical industries, the cabal that I have called the convenience-industrial complex.

The study’s authors wrote a more user-friendly Conversation article which starts with a discussion of what to do with a disposable coffee cup, which most people would put in the recycling bin. In reality, it is not recyclable. They note;

“In fact, the most sustainable option isn’t available at the trash bin. It happens earlier, before you’re handed a disposable cup in the first place.”

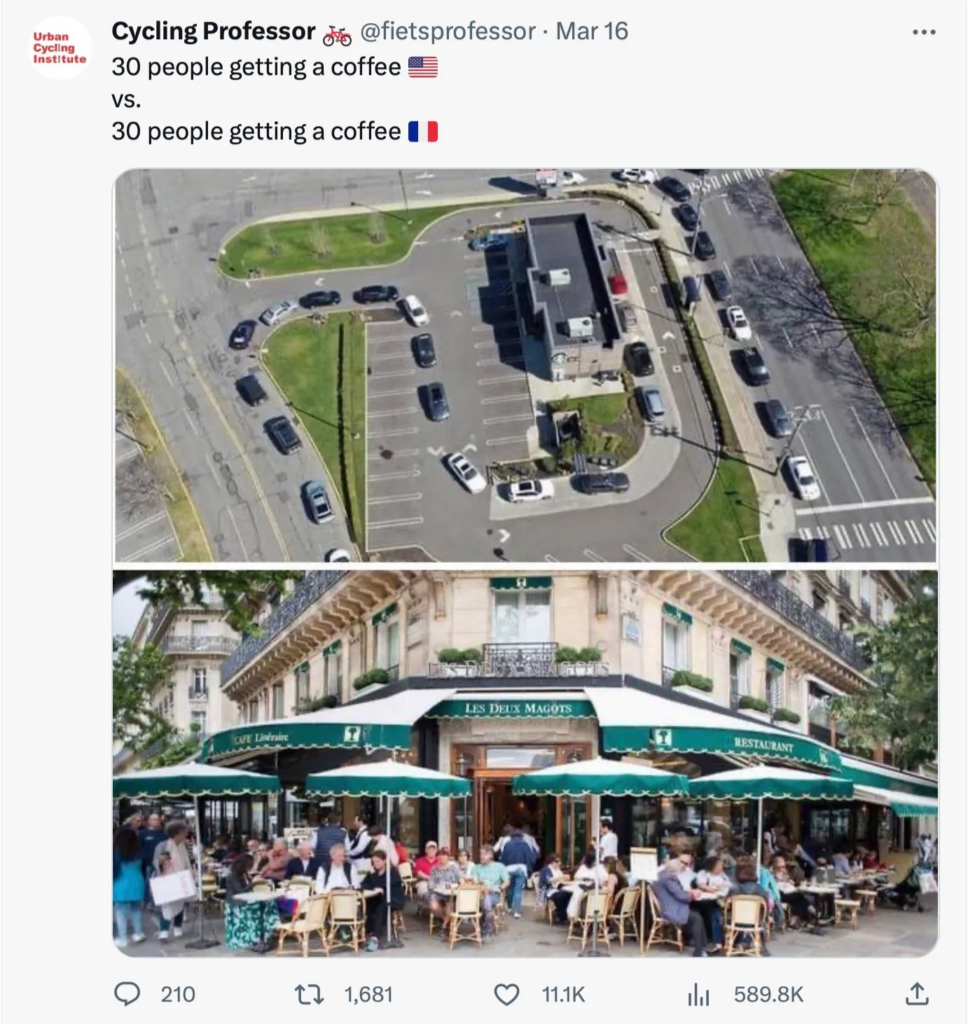

I have devoted a section of my upcoming book, The Story of Upfront Carbon, to the disposable coffee cup, where I note that the story is much bigger than the cup itself.

“The cup, the cupholder in the SUV that’s big enough to be a mobile dining room, the need to always be sipping something, that’s the system, the culture of convenience. That’s why we have to change the culture, not the cup.”

The idea of recycling is a critical part of this culture of convenience that has changed the world. I wrote about it for years on Treehugger and lectured about it for my Sustainable Design class at Toronto Metropolitan University. I explained how recycling was created by the bottling and packaging industry and their customers as a part of their successful campaign to shift responsibility for their product from the producer to us, the consumer.

This post is a sort of consolidation of my past writing and my lecture/slideshow:

75 years ago, if you wanted a cup of coffee or a bite to eat, you went to a restaurant or diner, sat down and got served your coffee in a porcelain mug and ate off a china plate. There were no litter bins on the street because there wasn’t much litter. It was pretty much a closed, circular system where the restaurant owner sold you food or coffee and kind of rented you the vessel from which you ate or drank.

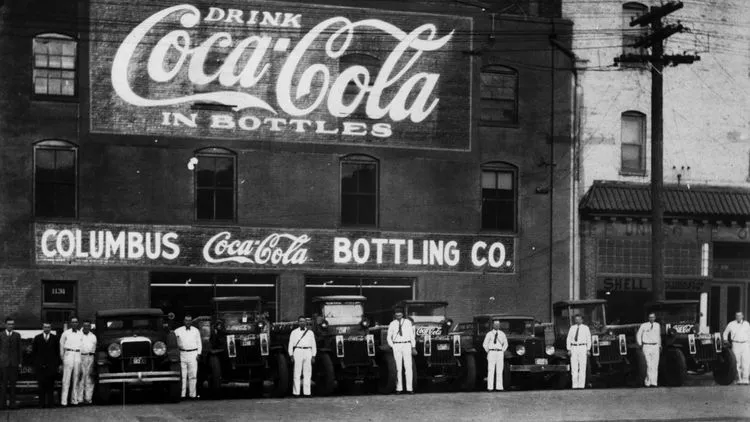

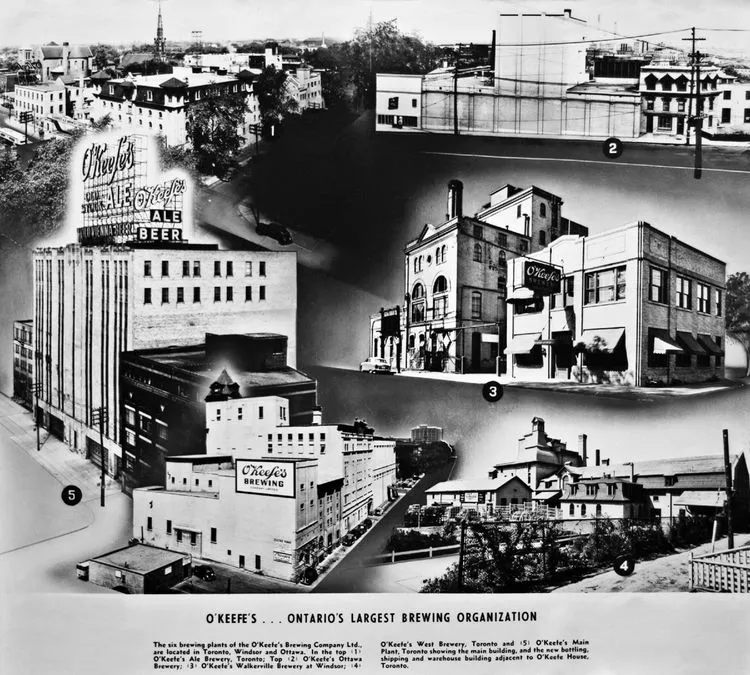

Soft drinks like Coke and hard drinks like beer were made and distributed locally because bottles were expensive and heavy so they were collected, washed and refilled, while transporting them two ways was slow and expensive. It was circular, with the producer taking responsibility for the product and its packaging, but circles operate most efficiently when they are smaller. So there were bottlers and breweries and dairies in every small city and town.

Take the example of O’Keefe Breweries, which had five breweries just in the Province of Ontario, serving a population of 6 million in 1960. It doesn’t even exist anymore. What happened?

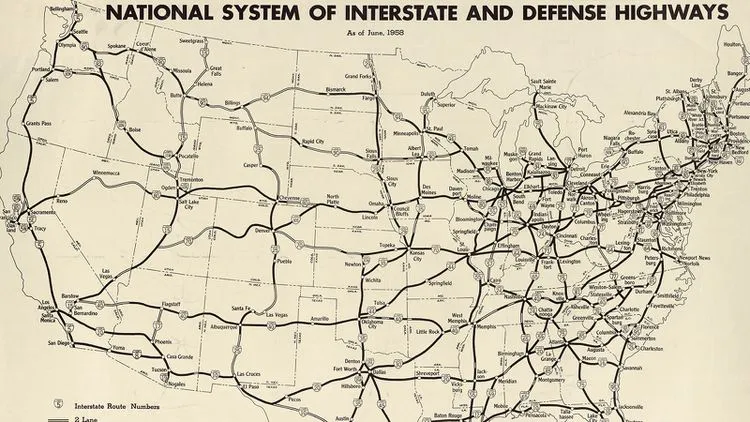

A triple whammy of highways, refrigerated trailers, and the great suburban expansion of the postwar years. And the hamburger.

The new highways and the new suburbs and the new mobility meant new ways of eating; there is no need to spend lots of money on places for people to sit down to eat, or to have wait staff to serve them, when they can sit in their cars. It was vastly more cost-effective to have disposable packaging and not have to worry about it after. So McDonalds and other drive-in and drive-through chains proliferated around the country. As Andrew Smith notes in his book Hamburger: A global history,

“This assembly-line system provided customers with fast, reliable and inexpensive food; in return, the McDonald brothers expected their customers to queue, pick up their own food, eat quickly, clean up their own rubbish and leave without delay, thereby making room for others.”

It was so convenient, fast and cheap. As Emelyn Rude writes in Time:

“By the 1960s, private automobiles had taken over American roads and fast-food joints catering almost exclusively in food to-go became the fastest growing facet of the restaurant industry.”

Now we were all eating out of paper, using foam or paper cups, straws, forks, everything was disposable. But while there may have been waste bins at the McDonalds’ parking lot, there weren’t any on the roads or in the cities; this was all a new phenomenon.

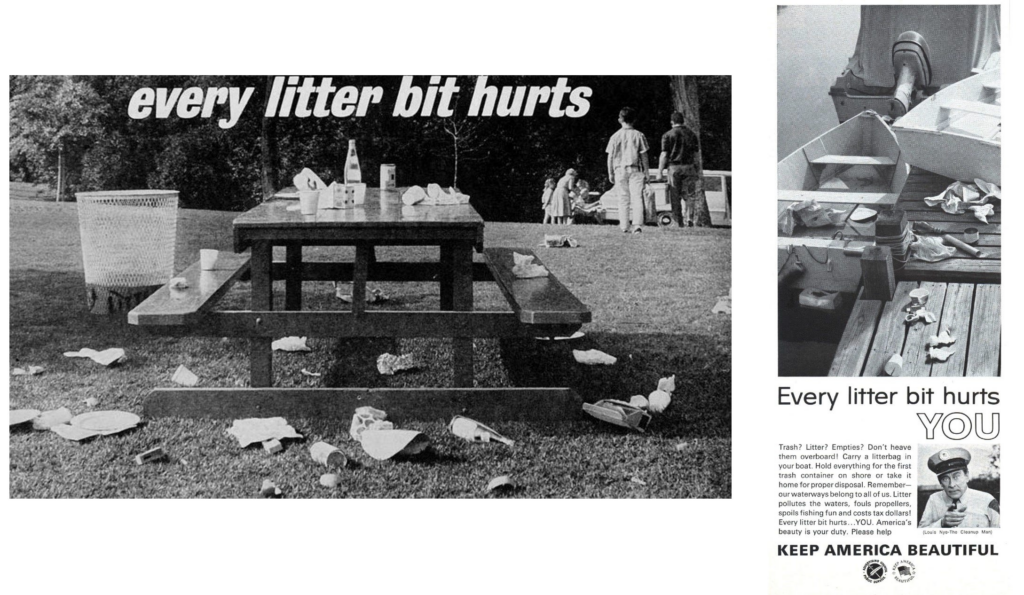

The problem was that people didn’t know what to do; they just threw their garbage out of their car windows or just dropped where they were. There was no culture of throwing things out, because when there were china plates and returnable bottles, there was no waste to speak of. We had to be trained.

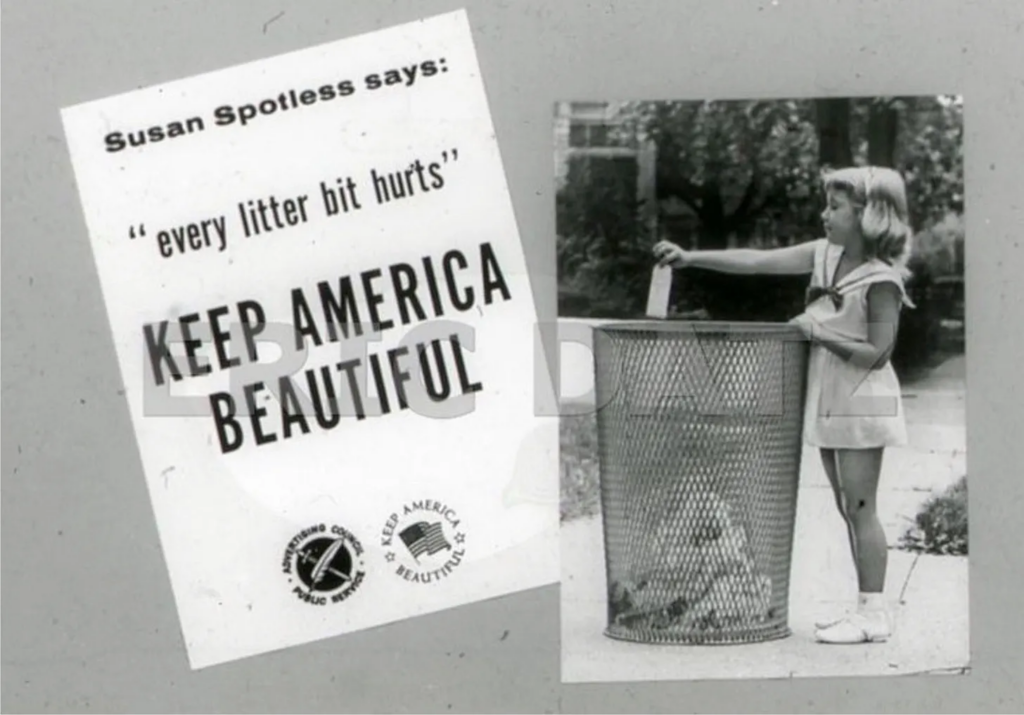

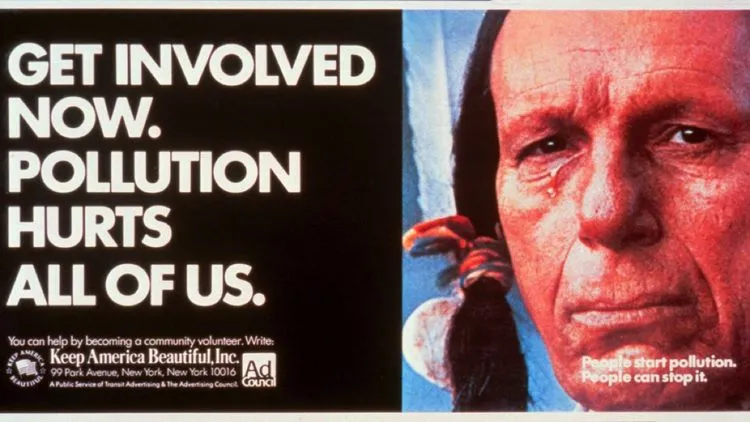

So the Keep America Beautiful (KAB) organization, founding members Philip Morris, Anheuser-Busch, PepsiCo, and Coca-Cola, was formed to teach Americans how to pick up after themselves with campaigns like “Don’t be a litterbug ’cause every litter bit hurts” in the sixties. Heather Rogers wrote in her wonderful essay, Message in a Bottle:

KAB downplayed industry’s role in despoiling the earth, while relentlessly hammering home the message of each person’s responsibility for the destruction of nature, one wrapper at a time. . . . KAB was a pioneer in sowing confusion about the environmental impact of mass production and consumption.

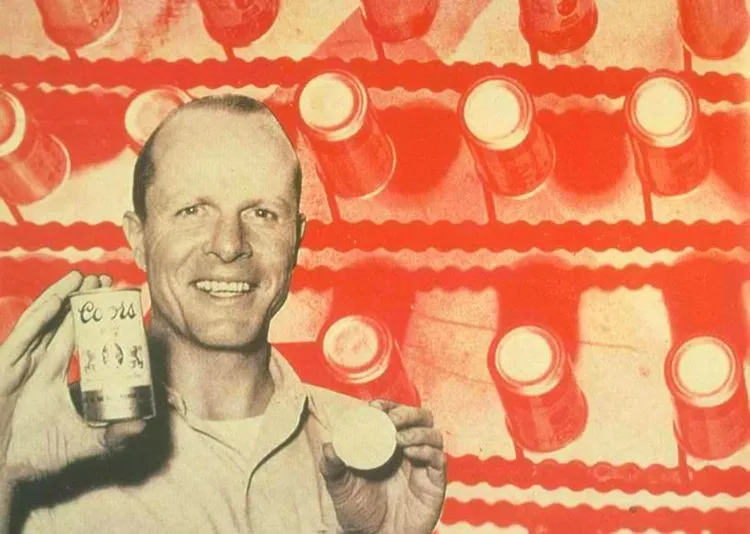

After Bill Coors perfected the two-part aluminum can and Coke and Pepsi started using disposable bottles and cans, the beer industry consolidated so that a single brewery in Golden, Colorado, could service almost the entire country and thousands of small breweries disappeared. Coca-Cola got rid of all the local bottlers and centralized production.

But this all only worked if responsibility for the bottles and cans shifted from the producer, who owned the packaging previously, to us, the consumer, who now bought them with their contents.

The trouble was, once we were all trained to pick up our garbage and put it in the wastebasket, it had to get picked up and landfilled by the municipalities. Heather Rogers writes:

With landfill space shrinking, new incinerators ruled out, water dumping long ago outlawed, and the public becoming more environmentally aware by the hour, the solutions to the garbage disposal problem were narrowing. Looking forward, manufacturers must have perceived their range of options as truly horrifying: bans on certain materials and industrial processes; production controls; minimum standards for product durability.

Local and State governments proposed bottle bills and deposits on everything, which would have sent the bottlers and the entire convenience industry back to the dark ages. So they had to invent recycling, where they promised it would be picked up and processed into new packaging.

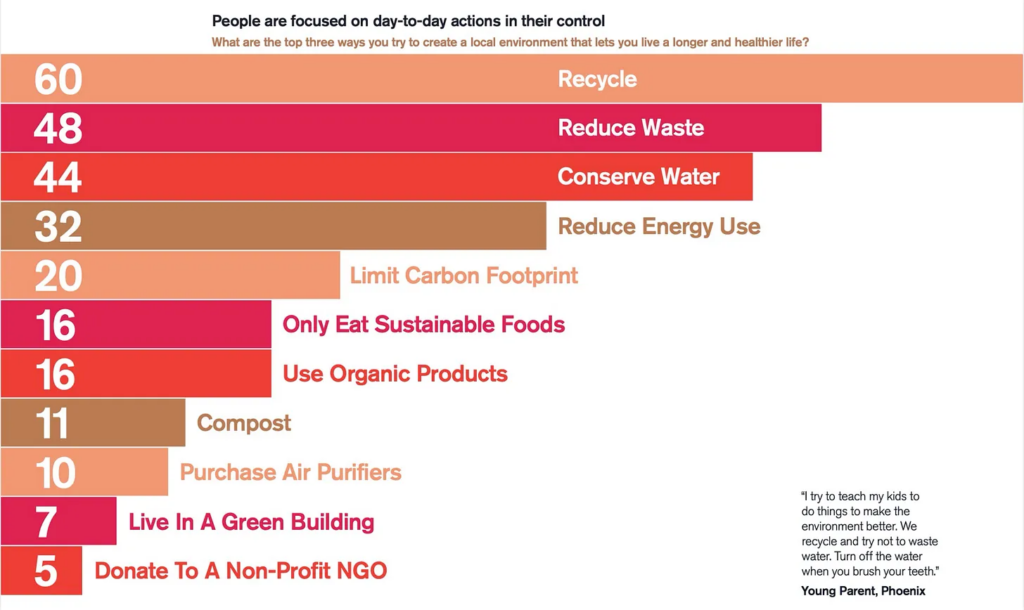

They did much more than just train us to pick up their garbage and separate it into piles; they taught us to love it. We are trained from our first Playmobil set that recycling is among the most virtuous things that we can do in our lives.

Studies have shown that for many people, it is the ONLY “green” thing that they do. And it is an extraordinary scam. We have come to accept that we should carefully separate our waste and store it, then pay serious taxes for men in special trucks to come and take it away and separate it further, and then try and recover the cost by selling the stuff, which turned out to be just about impossible.

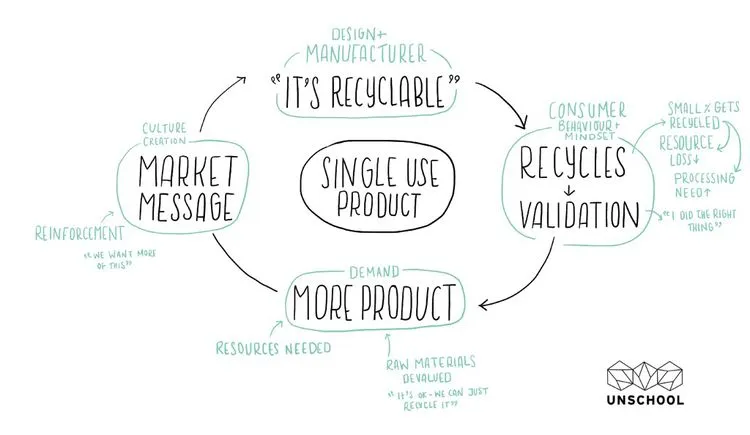

Leyla Acaroglu argues in Design for Disposability that recycling actually encourages consumption. We feel less guilty about throwing things away, and it gives us validation that we did the right thing. That becomes a license to buy more product, which leads to more production. She writes:

We are set to see a perpetuation of the addictive cycle that has led us to the mess we are in — that being the all-pervasive disposability practices that designers replicate, governments try to manage and clean up, and everyday citizens like you and me have to accept all of it as normal.

This is what has created the massive mess that we are in today. Within 50 years we have moved from everyday reusable products to single-use disposable items that are a blight on our wallets and the environment. Countries spend billions of dollars every year to build and manage landfills that just compress and bury this stuff. While people complain about dirty cities and giant ocean plastic waste islands, producers continue to deflect all responsibility for the end of life management of their products, and designers are complacent in the perpetuation of stuff designed for disposability.

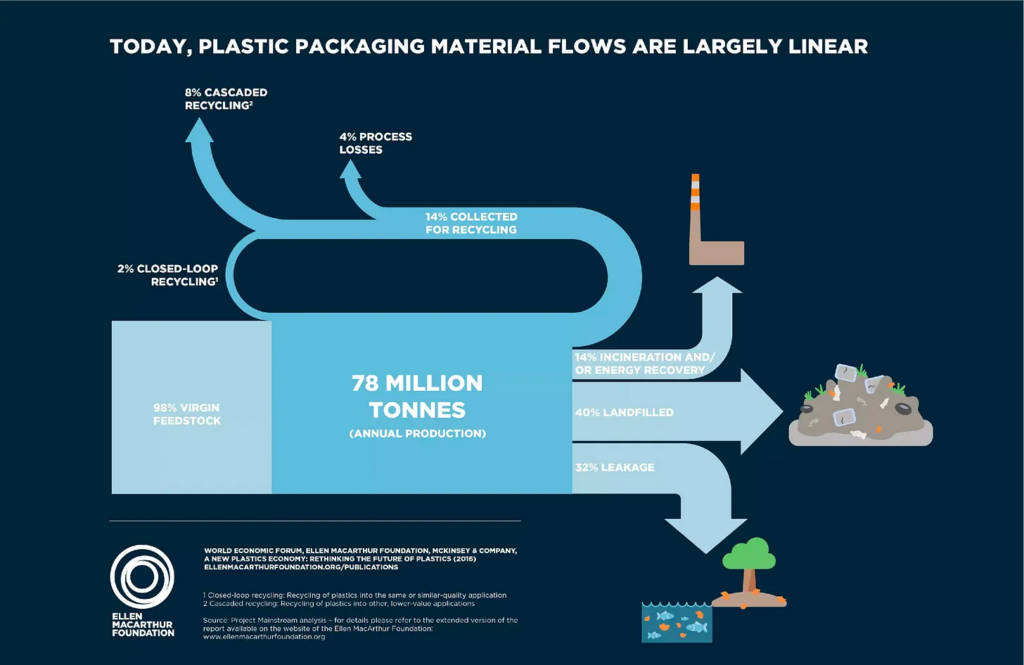

And it was all a scam and a lie; hardly anything was ever recycled. With plastics, only 14% was collected, 8% was downcycled into lumber and benches, and only 2% was actually truly recycled.

Today we have a giant system of big cups and big cupholders in big cars driving down big roads to big suburbs. The entire picture is driven by fossil fuel consumption, from the making of the single-use plastic to the filling of the gas tank in the mobile dining room. It couldn’t have been more petro-centric if the entire country had been designed by ExxonMobil.

This is why the concept of recycling has been such a spectacular success. The industry convinced us that single-use packaging would be dealt with, so that we could happily consume without concern. We continue to design for disposability on the assumption that Rocky’s recycling truck will pick it up and make it magically disappear. The petrochemical companies are making more plastic than ever, and restaurants are closing their dining areas and going to drive-thru only.

Our study authors call for change, concluding:

As waste-related pollution accumulates worldwide, corporations continue to shame and blame consumers rather than reducing the amount of disposable products they create. In our view, recycling is not a get-out-of-jail-free card for overproducing and consuming goods, and it is time that the U.S. stopped treating it as such.

Indeed. The concept of recycling was great for the industry, but not so good for the rest of us. They industry trained us well, but it’s past time to change this culture of convenience, to sit down and enjoy the coffee.