Consumption leads jobs: a comprehensive update – by New Deal democrat Yesterday I encountered a post on Seeking Alpha from the chief economist for a major trading platform, who probably makes in a week the amount I pocket in an entire year from my writing, who wrote: “if one loses one’s job, one likely spends less. If one witnesses colleagues lose their jobs, one may cut back on spending. If extended family members lose their jobs, spending may be reduced.” Here’s their accompanying graph: Note the heading: “consumption is still growing because jobs are expanding” This is an argument I encountered many times during the Great Recession: as more an more jobs were lost, it was a sure thing that people would spend less and less.

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: Consumption leads Employment, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

Consumption leads jobs: a comprehensive update

– by New Deal democrat

Yesterday I encountered a post on Seeking Alpha from the chief economist for a major trading platform, who probably makes in a week the amount I pocket in an entire year from my writing, who wrote:

“if one loses one’s job, one likely spends less. If one witnesses colleagues lose their jobs, one may cut back on spending. If extended family members lose their jobs, spending may be reduced.”

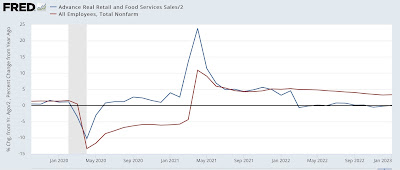

Here’s their accompanying graph:

Note the heading: “consumption is still growing because jobs are expanding” This is an argument I encountered many times during the Great Recession: as more an more jobs were lost, it was a sure thing that people would spend less and less.

Except for one thing: in the aggregate, it’s completely wrong.

Generally speaking, in recessions prices go down more (or go up less slowly) than wages. Interest rates paid for things like mortgages and car loans go down. As a result, even as jobs are still being shed, bargains simply become compelling for some people who are employed, and they go out and spend more. Similarly, even as jobs continue to get added to expanding economies, if prices and interest rates rise more than wages (as they typically do late in expansions), consumers in the aggregate start to cut back.

In short, it is the changes in consumption that lead to the change in employment, as sales growth or shortfalls lead employers to amplify or trim their hiring and firing.

Even shorter: consumption leads employment, not visa versa.

Since I haven’t run the graphs in support of this relationship in quite a while, let me re-post the evidence.

Here is a graph, going back 75 years through 2019, of the YoY% change in real retail sales (blue, /2 for scale) vs nonfarm payrolls (red), averaged quarterly:

While there’s not an exact 1:1 correspondence, the graphic evidence is simply compelling that the peaks and troughs in consumption YoY lead peak growth or losses in employment by one or more quarters. For 75 years.

Because the pandemic year of 2020 would make everything else before it look like squiggles, here’s the update since then:

The spending came first; then the job growth. Then consumer spending YoY went flat, and job growth has been decelerating.

Which leads me to a criticism of a second article I read yesterday, by Lance Roberts, formerly (if I recall correctly) of Time Magazine, a conservative commentator who is often my poster child for “someone is wrong on the internet.” Except most of his current argument – that the Fed is very unlikely to give us a “soft landing” – is correct. After noting that both sales growth and jobs growth have been decelerating, he wrote:

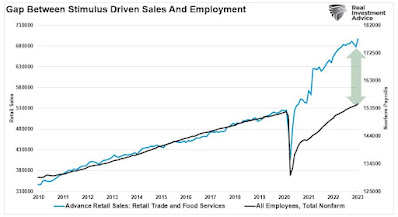

“While most of the jobs recovery was hiring back employees that were let go, the surge in stimulus-fueled retail sales will ultimately revert to employment growth. The reason is that people can ultimately only spend what they earn. As shown, the disconnect between retail sales and employment is unsustainable.”

I agree. Where I take issue is his graph in accompaniment to the point, shown below:

Note the differing left/right scales. The graph tends to imply a 1:1 relationship between retail sales growth and jobs growth. But that’s misleading, because as I’ve shown above real retail spending has tended to increase or decrease by twice the change in jobs. So let me show you the data since the modern retail sales series started in 1992 another way.

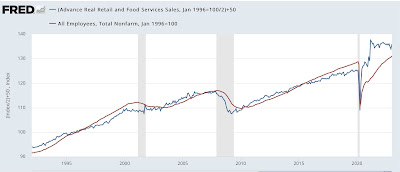

The below graph norms both real retail sales and nonfarm payrolls to 100 as of roughly mid-cycle for the 1990s. That’s because, as an outgrowth of the leading/lagging relationship, sales grow relatively more quickly than jobs earlier in expansions, and less quickly later. Then I do a little mathematical trick: dividing sales by 2 and adding 50 to result to arrive at advances and declines in real sales that equal changing at half the rate of jobs:

Note that the “shortfall” between job growth and retail sales growth appears considerably smaller than in Roberts’ graph. Here’s the close-up:

In the past 2.5 years, job growth has made up about 8/9’s of what it is needed for the relationship to return to trend. So, to be clear, I agree with Roberts’ assertion that “the surge in . . . retail sales will ultimately revert to jobs growth,” or more accurately, the two series will converge.

Exactly where and when that convergence will happen, we don’t know.

Foreboding Economic Signs Coming from consumption and employment data, Angry Bear, New Deal Democrat.