AB: This brief article gets right down to the basics in where costs are added and impacting the prices to the consumer. It is simple and straight to the point of how PBMs impact the prices to the consumer. Very little or nothing was contributed by myself to this article by the authors Inmaculada Hernandez; Nico Gabriel; Anna Kaltenboeck. The table and figure are products of JAMA. Why is it on Angry Bear? Because of its simplistic approach to identifying the costs impacting pharma prices to the customer. It is a good read and educational of one way prices are impacted. A deeper dive soon. Reimbursement to Pharmacies for Generic Drugs by Medicare Part D Sponsors, JAMA Network, Inmaculada Hernandez; Nico Gabriel; Anna Kaltenboeck. The Issue . .

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: Healthcare, JAMA Network, PBMs, Pharamaceuticals

This could be interesting, too:

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes RFK Jr. blames the victims

Joel Eissenberg writes The branding of Medicaid

Bill Haskell writes Why Healthcare Costs So Much . . .

AB: This brief article gets right down to the basics in where costs are added and impacting the prices to the consumer. It is simple and straight to the point of how PBMs impact the prices to the consumer. Very little or nothing was contributed by myself to this article by the authors Inmaculada Hernandez; Nico Gabriel; Anna Kaltenboeck. The table and figure are products of JAMA.

Why is it on Angry Bear? Because of its simplistic approach to identifying the costs impacting pharma prices to the customer. It is a good read and educational of one way prices are impacted. A deeper dive soon.

Reimbursement to Pharmacies for Generic Drugs by Medicare Part D Sponsors, JAMA Network, Inmaculada Hernandez; Nico Gabriel; Anna Kaltenboeck.

The Issue . . .

Pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) manage prescription drug benefits on behalf of health insurers; PBMs negotiate reimbursements for drugs, which should cover drug acquisition cost and pharmacy’s cost to dispense. Studies in Medicaid suggest that some PBMs pay pharmacies unjustified excessive amounts for generics, as high as 10 times acquisition costs.1 By inflating the amount paid to pharmacies, PBMs make patients pay more because patient cost sharing is based on point-of-sale reimbursement. The PBMs recover significant portions of point-of-sale reimbursement through claw backs, which PBMs use opaquely. Inflation of point-of-sale reimbursement may also enable PBMs that own chain pharmacies to shift profits to the pharmacy.1 Under-standing whether these reimbursement practices take place in Medicare is important to inform ongoing policy efforts.

Generic over-reimbursement is one of the target areas identified by the Senate Finance Committee for PBM reform.2

The study evaluates whether organizations offering Medicare Part D plans (Part D sponsors) overpay pharmacies for generic drugs. Part D sponsors use PBMs to manage their prescription drug benefits. In some instances, PBMs act as Part D sponsors, directly offering Part D plans.

Methodology

We identified the top 50 generic drugs by Part D spending in 2021, using the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services dashboard (eTable in Supplement 1). For each drug, we selected the formulation with the highest use based on Medicare claims. From quarter 1, 2021, formulary files, we obtained the median amount a Part D plan reimbursed an in-area pharmacy for each generic drug at point of sale.3 This amount does not distinguish reimbursement to pharmacies based on inclusion in preferred networks. We estimated the ratio between this amount and drug acquisition cost using quarter 1, 2021, National Average Drug Acquisition Costs. The resulting reimbursement to cost ratio represents reimbursement from Part D plans to pharmacies relative to the pharmacy’s cost to acquire the drug. We excluded Medicare Advantage prescription drug plans and estimated the mean reimbursement to cost ratio across all stand-alone prescription drug plans.

To understand how reimbursement patterns differed by organization offering each Part D plan, we summarized results at Part D sponsor level. For each Part D sponsor, we reported the mean reimbursement to cost ratio and number of drugs reimbursed at over 10 times acquisition cost. This threshold has been previously used to identify generic drugs with unjustified excessive reimbursement.4 For the subset of drugs reimbursed at over 10 times cost by at least 1 Part D sponsor, we reported acquisition costs and reimbursement rates. Analyses were performed in SAS version 9.4 for the top 6 Part D sponsors, which account for 90% of Part D enrollment.5

Results

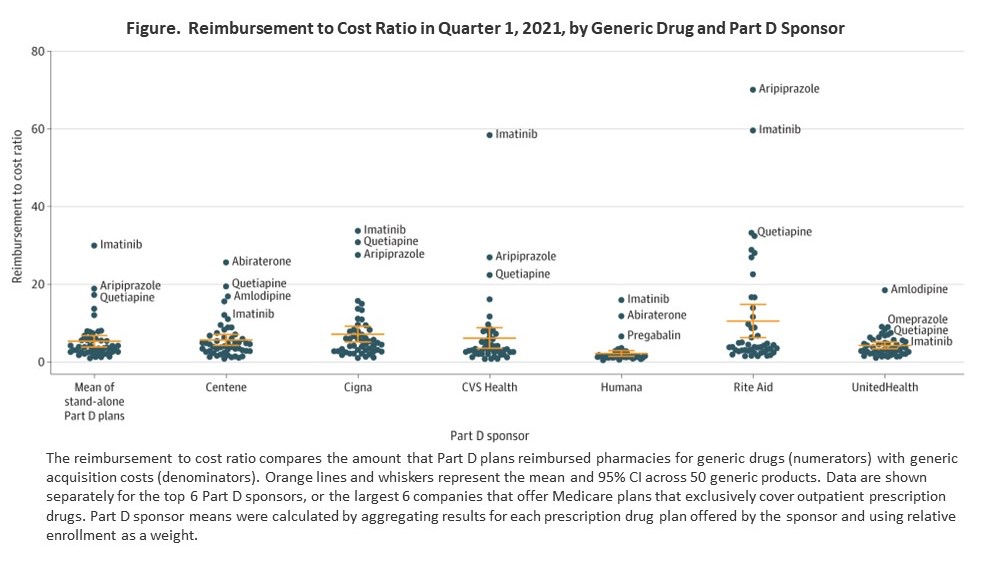

Part D plans reimbursed generics at a mean of 5.4 times acquisition costs (95% CI, 3.9-6.8). Reimbursement rates were highest for Rite Aid (reimbursement to cost ratio, 10.6; 95% CI, 6.3-14.9; mean reimbursement, $8.6/unit), followed by Cigna (7.2; 95% CI, 5.2-9.2; $4.9/unit), CVS Health (6.2; 95% CI, 3.6-8.8; $6.8/unit), Centene (5.7; 95% CI, 4.3-7.1; $3.5/unit), UnitedHealth (4.3; 95% CI, 3.4-5.1; $1.5/unit), and Humana (2.2; 95% CI, 1.5-3.0; $2.4/unit) (Figure). Rite Aid reimbursed 12 drugs at over 10 times cost, followed by Cigna (9 drugs), Centene (6 drugs), CVS Health (5 drugs), Humana (2 drugs), and UnitedHealth (1 drug).

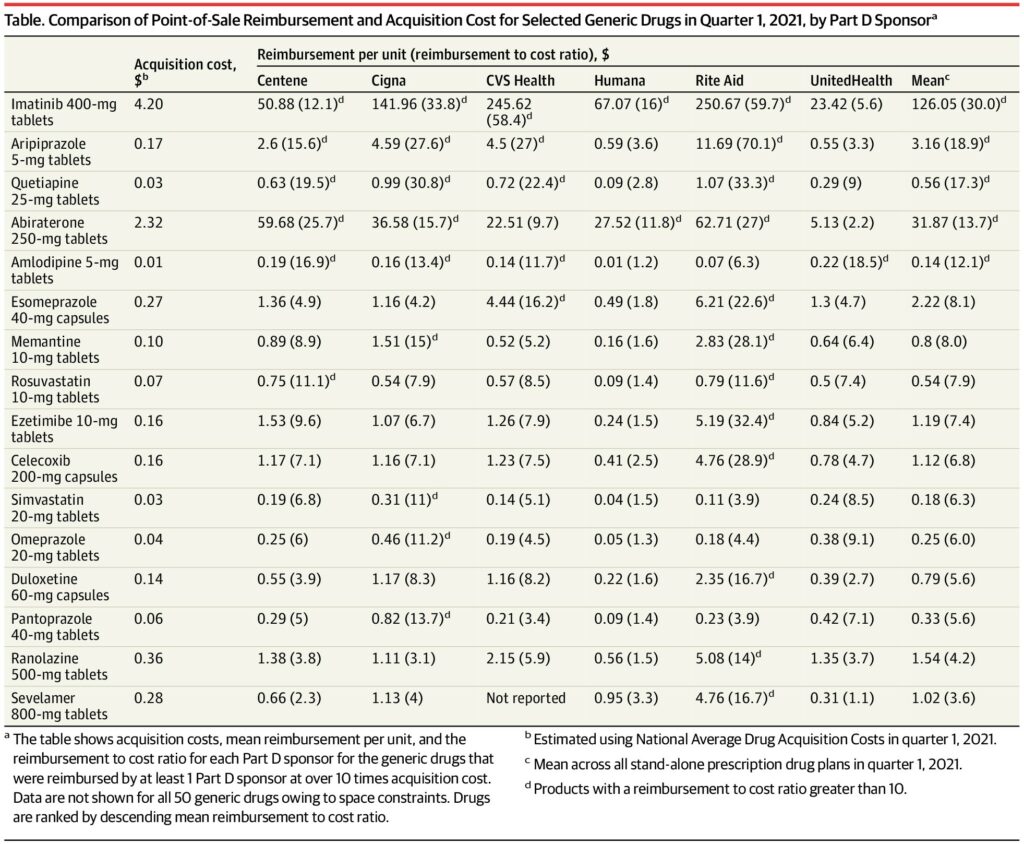

Imatinib 400 mg and aripiprazole 5 mg had the largest reimbursement to cost ratios (Table ). Imatinib 400 mg had an acquisition cost of $4.20 per tablet but was reimbursed at a mean of $126.05 per tablet. Aripiprazole 5 mg had an acquisition cost of $0.17 per tablet but was reimbursed at a mean of $3.16 per tablet.

Discussion

Part D sponsors provided excessive point-of-sale reimbursements to pharmacies for certain generic drugs compared with acquisition costs. Study limitations include unavailability of data on postsale adjustments that claw money from pharmacies back to Part D sponsors, which may offset point-of-sale reimbursements6; uncertainty around the optimal reimbursement to cost ratio; and lack of investigation of how reimbursement per unit may differ with quantity dispensed. Nevertheless, findings are concerning because generics represent over 90% of dispensed prescriptions, and excessive reimbursements result in increased patient out-of-pocket costs. Further investigation of the consequences associated with generic drug reimbursement practices by Part D sponsors is warranted.

Footnotes

1. Sunshine in the black box of pharmacy benefits management: Florida Medicaid pharmacy claims analysis. January 27, 2020. Accessed March 3, 2023. https://ncpa.co/pdf/florida-3aa-medicaid-pharmacy-analysis.pdf

2. Senate Finance Committee. A bipartisan framework for reducing prescription drug costs by modernizing the supply chain and ensuring meaningful relief at the pharmacy counter. April 20, 2023. Accessed June 15, 2023. https://www.finance.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/042023%20SFC%20Framework%20for%20Rx%20Supply%20Chain%20Modernization.pdf

3. Prescription drug plan formulary, pharmacy network, and pricing information files for order. Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/Research-Statistics-Data-and-Systems/Files-for-Order/NonIdentifiableDataFiles/PrescriptionDrugPlanFormularyPharmacyNetworkandPricingInformationFiles

4. Maine Health Data Organization. Prescription drug transparency report. December 14, 2022. Accessed March 20, 2023. https://mhdo.maine.gov/_pdf/MHDO%20Rx%20Transparency%20Report_221213.pdf

5.Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Medicare Advantage/Part D contract and enrollment data. Accessed March 21, 2023. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/mcradvpartdenroldata

6. Medicare Payment Advisory Commission. Report to the Congress: Medicare and the health care delivery system. June 2023. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://www.medpac.gov/wp-content/uploads/2023/06/Jun23_MedPAC_Report_To_Congress_SEC.pdf