Delightful story on how US pharmaceutical companies shift profits overseas. And US citizens are paying the highest prices globally for lifesaving meds which other countries our paying roughly one third. Pharma is also shifting their profits overseas and minimizing US taxes or tax avoidance. One way to avoid taxes is to move intellectual property to the country of choice or the no-tax jurisdictions in the Caribbean and Europe. Parking intellectual property such as the patents in low tax countries gives them a legal monopoly to avoid US taxes. Add in overseas manufacturing, and almost all profits earned on US sales were shifted to the low-tax jurisdictions. Trick That Helps Big Pharma Companies Avoid Paying Billons in US Taxes, business

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: Healthcare, Pharmaceuticals, politics, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Delightful story on how US pharmaceutical companies shift profits overseas. And US citizens are paying the highest prices globally for lifesaving meds which other countries our paying roughly one third. Pharma is also shifting their profits overseas and minimizing US taxes or tax avoidance.

One way to avoid taxes is to move intellectual property to the country of choice or the no-tax jurisdictions in the Caribbean and Europe. Parking intellectual property such as the patents in low tax countries gives them a legal monopoly to avoid US taxes. Add in overseas manufacturing, and almost all profits earned on US sales were shifted to the low-tax jurisdictions.

Trick That Helps Big Pharma Companies Avoid Paying Billons in US Taxes, business insider.com, Brad Setser and Tess Turner

Americans are not only paying through the nose for their prescriptions but also receiving none of the benefits from having a robust “American” pharmaceutical industry. Tyler Le @ Insider

There’s a mystery lurking in America’s national medicine cabinet.

Americans pay the highest prices in the world for lifesaving medicines. This is roughly triple what people in the world’s other big economies pay for the same name-brand, on-patent drugs. The cost of producing a medicine generally doesn’t vary much. So it stands to reason the US’s big pharmaceutical companies should earn far more in the US than they earn elsewhere. Simple math.

But take a look at the corporate disclosures of America’s largest pharmaceutical companies, and a puzzling hole opens.

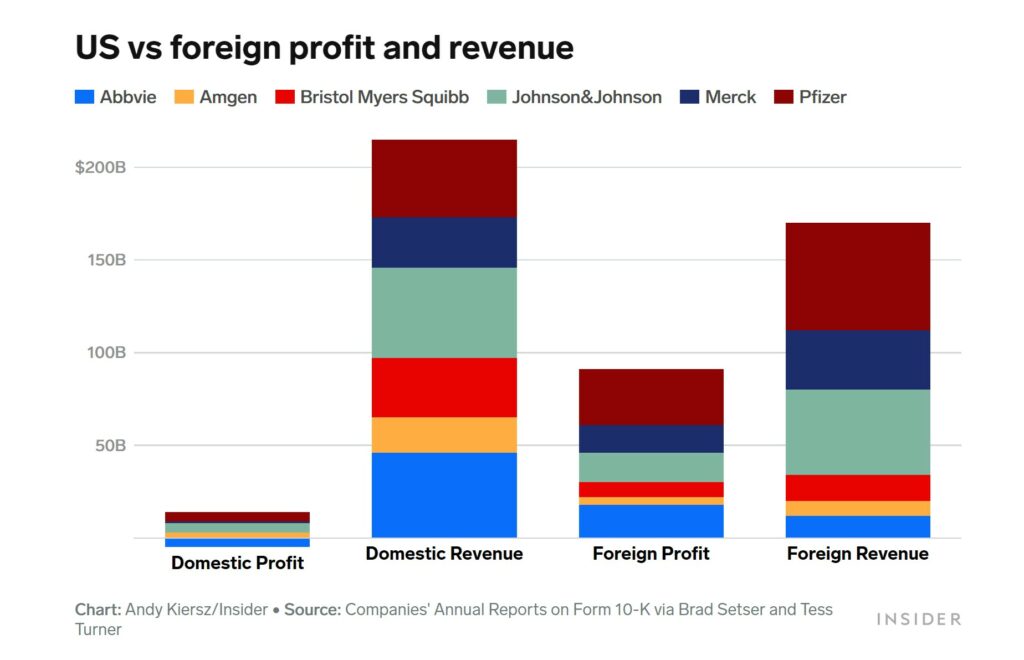

The six major US pharmaceutical firms provide fairly detailed data reported making $215 billion worth of sales in the US for 2022. Given America’s systematically higher prices, their sales abroad were logically more modest and totaling $170 billion. Despite this discrepancy, the companies reported earning little in profits. In some cases, they report absolutely nothing in the US. Of their $100 billion combined profit, the companies said $90 billion was made abroad. While $10 billion came from their US operations. This comes out to a profit margin of 5% in the US and a margin of over 50% abroad. What’s going on?

(Sorry, I can not do interactive charts (yet), You can find the same chart(s) at the Insider.)

Tax avoidance grants them the ability to do such.. When questioned, pharmaceutical companies respond they pay all the tax they legally owe. A Merck representative, for example, said that Merck,

“complies with all tax rules on a worldwide basis.”

The explanations are little more than a smoke screen. Most of America’s major pharmaceutical companies have simply perfected the art of legally shifting the profit on their US sales out of the country to low-tax jurisdictions.

Planned Tax avoidance. When questioned, pharmaceutical companies inevitably respond that they pay all the tax that they legally owe. A Merck representative, for example, said that Merck “complies with all tax rules on a worldwide basis.” But these explanations are a smoke screen. Most of America’s major pharmaceutical companies have simply perfected the art of legally shifting the profit on their US sales out of the country to low-tax jurisdictions.

It is allowed by the tax law and it still is outrageous. Americans are paying through the nose for their prescriptions and , they are not receiving the benefits from having a robust “American” pharmaceutical industry. The tax revenues from US sales are being paid abroad, rather than being reinvested in new research at the National Institutes of Health. Pharmaceutical-manufacturing jobs are being created abroad, rather than at home.

While the battle to lower drug prices is likely to drag on for years, there are clear ways for the US to prevent this sort of profit shifting. Doing such will not only make the tax system fairer but also allow Americans to recapture some of the value they’re creating for these giant companies.

Pay no attention to the profits behind the curtain

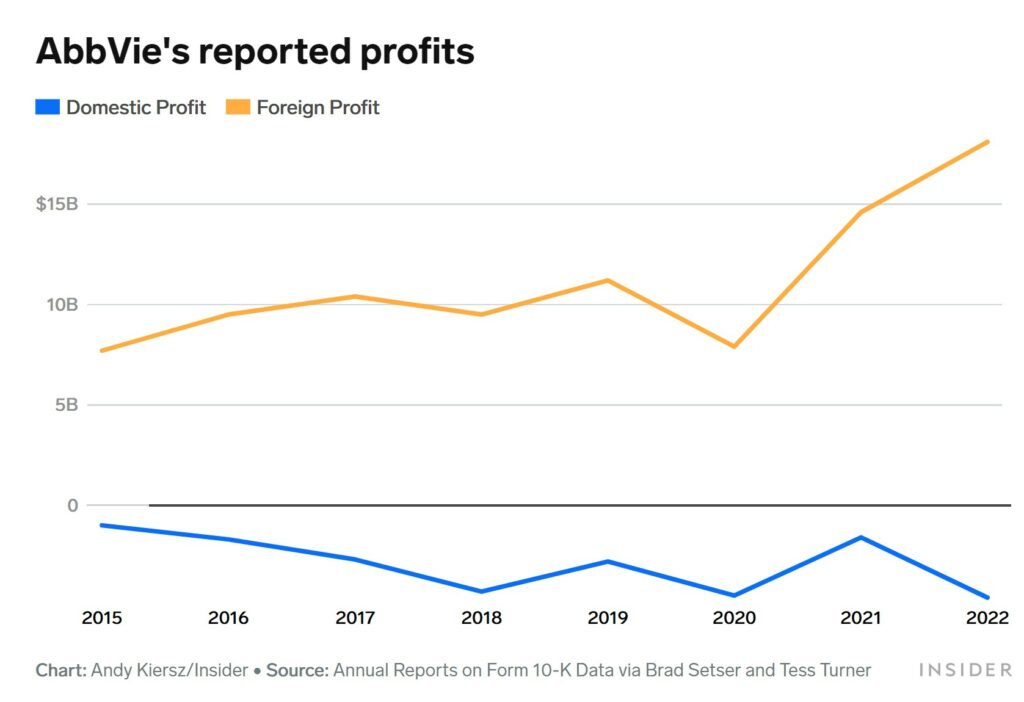

To get a sense of how much money these pharmaceutical companies are moving around, it’s useful to look at a case study. Take AbbVie, the producer of the blockbuster immunosuppressive drug Humira. Humira is used to treat a variety of conditions, including arthritis and Crohn’s disease.

An investigation by Democratic Sen. Ron Wyden of Oregon found the company booked 99% of its profit abroad in 2020, despite generating only three-quarters of its sales overseas. More recently, AbbVie claimed it is actually losing money in America: The company reported a $5 billion loss on its US operations in 2022, while generating a $18 billion profit outside the US. Rather remarkably, AbbVie reported only $12 billion in non-US sales, meaning its reported profit outside the US exceeded its revenue.

Humira has earned $208 billion globally since it was first approved in 2002 to ease the symptoms of rheumatoid arthritis. It has since been authorized to treat more autoimmune conditions, including Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis. Patients administer it themselves, typically every week or two, injecting it with a pen or syringe. In 2021, sales of Humira accounted for more than a third of AbbVie’s total revenue. How a Drug Company Made $114 Billion by Gaming the U.S. Patent System – The New York Times

AbbVie is an especially poignant example, but it’s hardly alone.

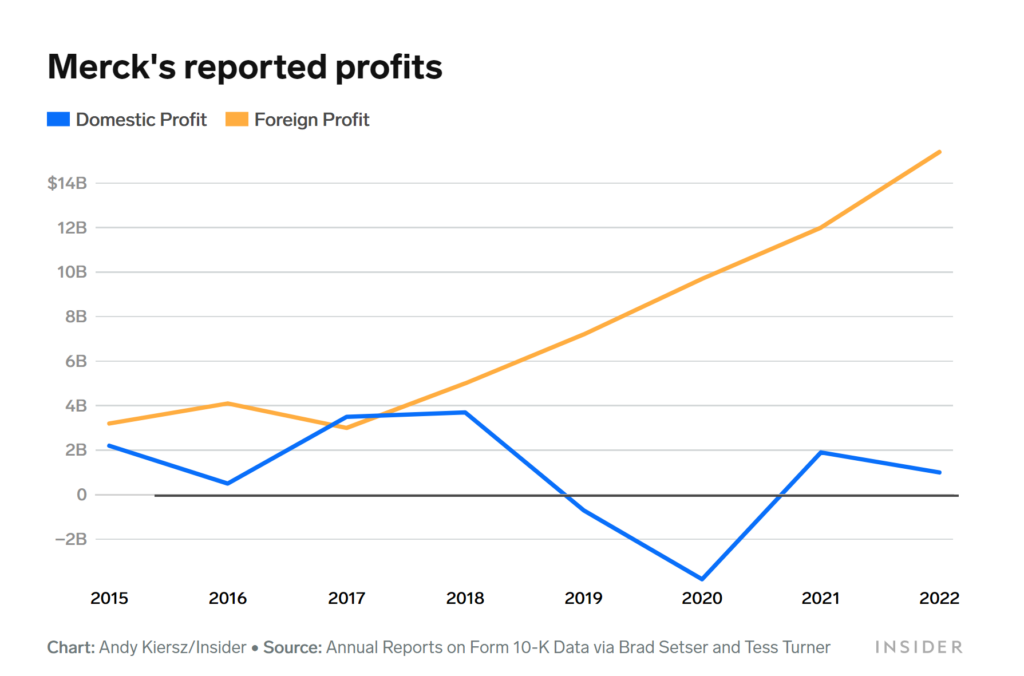

Merck, the maker of the blockbuster (and expensive) drug Keytruda, reported earning only $1 billion in profit on its $27 billion in US sales in 2022, while reporting that it earned $15 billion abroad on its $32 billion in sales overseas.

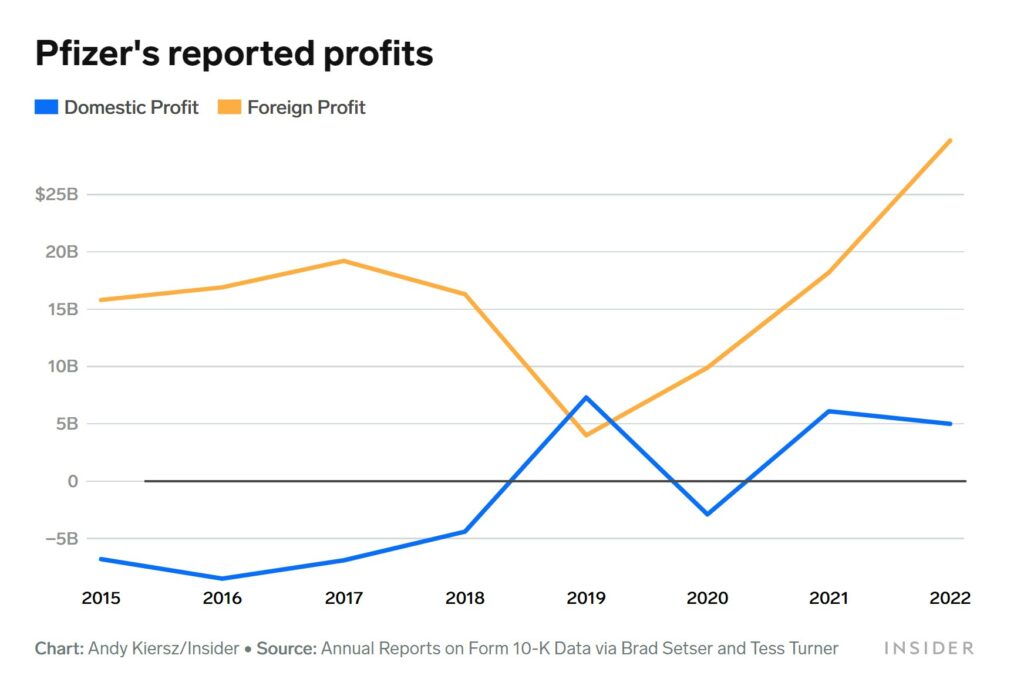

Pfizer produced the first mRNA coronavirus vaccine, now reports and unlike in the past, it is making a bit of money in the US. Even then, the discrepancy is quite large: $5 billion in the US in 2022 and $30 billion abroad. Before the surge in revenues and profits associated with its successful vaccine, Pfizer somehow always seemed to lose money in the US.

At this point, profit shifting is the industry norm:

Of the eight biggest US pharmaceutical companies, only Gilead reports earning the majority of its income in the US. The other seven companies appear to have paid the US government just over $2 billion on their $108 billion global profit in 2022 (this sum includes Eli Lilly, which reports the distribution of its tax payments but not the distribution of its earnings).

Governments outside the US actually collected more tax revenue from these seven “American” pharmaceutical companies than the US government: $11.5 billion.

Large legal loopholes

The offshore migration of these pharmaceutical companies’ profits may seem egregious, but the tax gymnastics are generally legal. In fact, the US corporate-tax code effectively incentivizes American pharmaceutical companies to play this game.

On paper, America’s corporate-tax rate is 21%, but the country’s largest and most profitable pharmaceutical companies don’t pay anything close to that. The effective tax rate for most of the big pharmaceutical companies profits they keep in the US is much closer to 10%. Since most of their profits are shifted overseas, the eight largest US pharma companies end up paying only about 3% of their global profit to the US Treasury. Most average American households have a far-higher tax burden.

A Companies’ ability to keep their US tax bill low is made possible by the US’s treatment of money made overseas. Through 2017, US companies were allowed to indefinitely defer US tax payments of profits earned offshore. Unsurprisingly, many companies also found ways to move profits to no-tax jurisdictions in the Caribbean and Europe. The most common way to do this was by parking their intellectual property such as the patents that give them a legal monopoly to sell a drug they’ve developed in no or low-tax jurisdictions. Add in overseas manufacturing, and almost all profits earned on US sales were shifted to the low-tax jurisdictions.

AbbVie, for example, located the right to profit from Humira in its Bermuda subsidiary and manufactured the drug in Puerto Rico, which is considered outside the US for tax purposes since the island is a territory rather than a state. All the profit for the drug was technically attributed to the division in no-tax Bermuda. This occurs even though the profits were being legally booked as profits in the Caribbean or Irish subsidiary of a US firm. In many cases, these companies kept the funds in a US bank account or invested in US bonds. The firms could even take out a loan in the US using the overseas cash as collateral, so clearly the money wasn’t “trapped” offshore.

The overall result was a mess and there is no doubt the corporate-tax code needs to be reformed.

But instead of solving the problem, the 2017 Trump corporate-tax reform made it worse. The law imposed a special 10.5% tax rate on profits made outside the US. This would seem to solve the issue. Money parked in other countries would still be subject to collection from the Treasury. However, the new rules allow companies to blend all of their foreign profits together in one big pot. A company with some profits in a high-tax country such as Germany could use its mandatory payments there to offset some of the earnings attributable to no-tax jurisdictions such as Bermuda.

It could not do the same with its US profit. With a bit of accounting, companies could avoid paying the minimum tax on their offshore income. The overall result was an “America last” tax code: US pharmaceutical firms got a big tax cut, while the incentive to move production of new drugs to low-tax jurisdictions such as Ireland remains.

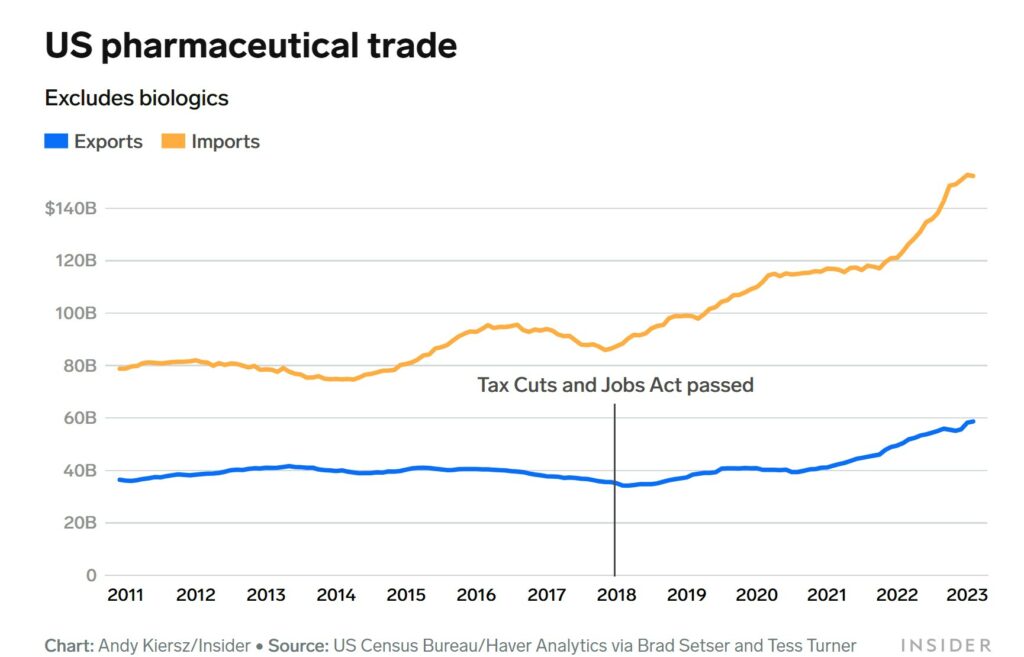

US trade data corroborates this story. The US has a large trade deficit in pharmaceutical products with other countries. The bulk of the imports are coming from low-tax jurisdictions such as Ireland, Singapore, Switzerland, and Belgium. Even the companies themselves report to their shareholders they pay low effective rates because of tax-haven countries. Merck’s latest annual 10-K report explained the differentials in tax rates were due to “operations in jurisdictions with different tax rates than the US. In particular, Ireland and Switzerland, as well as Singapore and Puerto Rico were named in the report..” None of this is particularly hidden.

What’s more, the super low rate enjoyed by American pharmaceutical companies is not necessary for these firms to be internationally competitive. Denmark’s Novo Nordisk reports paying tax at about the Danish corporate rate (22%), and it pays tax mostly in Denmark, even though its biggest market is the US. Even Switzerland’s Novartis pays the majority of its tax in Switzerland.

To add insult to injury, in many cases, these profits come from drugs developed through research made possible by National Institutes of Health funding and US tax credits for research and development. Despite this support, the US gets neither the biopharmaceutical-manufacturing jobs nor the tax revenues from these medicines. Pharmaceuticals brought to market by US companies it gets stuck with only the tab. If it sounds like a raw deal, that’s because it is.

A spoonful of medicine to make the taxes go down

America’s pharmaceutical companies have made great contributions to medicine. But there’s no reason to think they wouldn’t make the same contribution to human health if they actually paid US taxes on the profits from their US sales. Economic theory and global practice show any increase in their income taxes would be absorbed by the shareholders of the big pharmaceutical companies and not those buying their drugs. The pharmaceutical companies already charge the absolute maximum possible on their patent-protected medicines. They certainly aren’t doing so to cover the cost of their nonexistent US tax bill.

Common-sense reforms can help end this practice. One idea is to subject all overseas profits to a 15% minimum tax, assessed on a country-by-country basis to avoid accounting tricks. Another is to place limits on pharmaceutical firms’ ability to claim tax credits for research on the development of drugs when the intellectual property is then shifted outside the US. This would also eliminate the incentive to offshore pharmaceutical production and US jobs.

The net result would be more biopharmaceutical investment in the US, more tax revenues for the US Treasury, and a more resilient and more innovative US economy.