The USPS is an entity on to itself and is called out in the U.S. Constitution. For years it has functioned quite while even with Congress (Senator Collins) placing requirements upon it to fully fund parts of no commercial business in the US is required to do. The USPS is not a commercial business. It is an entity serving the population of the United States with the delivery of mail anywhere in the US regardless of cost. Somewhere along the way, Congress and outsiders seem to believe it is to be profitable as measured by other standards which have failed in the past. So here we are, with one person driving its needs based upon his business knowledge which do not and should not have application. Read on, retired Prof. Steve Hutkins continues his

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: Hot Topics, Journalism, OCT 2023, politics, Save The Post Offfice Blog, Steve Hutkins, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

Robert Skidelsky writes Lord Skidelsky to ask His Majesty’s Government what is their policy with regard to the Ukraine war following the new policy of the government of the United States of America.

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Ken Melvin writes A Developed Taste

The USPS is an entity on to itself and is called out in the U.S. Constitution. For years it has functioned quite while even with Congress (Senator Collins) placing requirements upon it to fully fund parts of no commercial business in the US is required to do. The USPS is not a commercial business. It is an entity serving the population of the United States with the delivery of mail anywhere in the US regardless of cost.

Somewhere along the way, Congress and outsiders seem to believe it is to be profitable as measured by other standards which have failed in the past. So here we are, with one person driving its needs based upon his business knowledge which do not and should not have application.

Read on, retired Prof. Steve Hutkins continues his talk on the state of the United States Postal Service.

USPS issues final environmental impact statement on new delivery fleet, lawsuits to resume shortly, Save the Post Office, Steve Hutkins, October 17, 2023

Late last month the Postal Service released the final version of the Supplemental Environmental Impact Statement (SEIS) concerning its purchase of a new fleet of delivery vehicles. The Postal Service would like the Final SEIS to be the last word, but its lack of responsiveness to criticisms of the Draft means that the lawsuits over the purchase plan will soon resume.

This Final SEIS is almost identical to the Draft SEIS that was released back in June. The Postal Service has essentially rejected nearly all the comments and criticisms made in response to the Draft by the EPA, the Attorneys General of fifteen states, the UAW, and several environmental groups.

About the only significant difference between the Draft and Final SEIS is that the final version contains the letters submitted in response to the Draft, with a table summarizing these comments and those made at the public hearing, along with the Postal Service’s answers. For nearly every comment, the Postal Service simply defends its previous analysis and decisions. The comments had virtually no impact on the Final SEIS.

A review of the two documents shows only a handful of minor changes. One involves insertion of a new passage explaining why postal delivery vehicles are different from other EVs and can’t be fairly compared. A second involves revised calculations monetizing the damages associated with greenhouse gas emissions, a change apparently made due to recommendations made by the EPA. A partial list of the differences between the Draft and Final SEIS is here.

The FEIS for the original plan from December 2021 is here. The Draft SEIS is here, and the Final SEIS is here. For easy access, the written comments submitted on the Final SEIS are here, the transcript of the public hearing on July 26, 2023, is here, and the Postal Service’s summary of the comments and its responses is here.

The lawsuits

The original purchase plan, which included only 10 percent EVs, was challenged in federal court in two cases. The plaintiffs alleged that the Postal Service violated NEPA by awarding a contract prior to initiating the environmental review, and it failed to analyze reasonable alternatives and take a “hard look” at environmental impacts.

The plaintiffs in CleanAirNow v. DeJoy include Sierra Club, Earthjustice, the Center for Biological Diversity, and the Attorneys General of fifteen states and the District of Columbia. NRDC v. DeJoy includes the UAW as plaintiff.

After the cases were filed in April 2022, the Postal Service upped the number of EVs to 62 percent of the first purchase and proceeded to do a Supplemental EIS on the new plan. Both legal cases were stayed while the Postal Service prepared the SEIS.

While acknowledging the increased percentage of EVs, the commenters on the Draft SEIS, which include those who filed the lawsuits, argue that the Postal Service again failed to consider a wide range of alternatives, including 90 to 100 percent EVs, and they again criticize the Postal Service for making a deal to buy vehicles without waiting for the completion of the environmental review.

In its comments, the UAW says that the Postal Service, rather than considering alternatives and examining the broader socioeconomic and environmental impacts resulting from its procurement decisions, “enshrined its decision with what amounts to a sham process designed to support USPS optically in pending litigation without seriously considering a full array of alternatives and impacts in the manner required by NEPA.” .

Now that the final SEIS has been issued, there’s a 30-day waiting period, and then the Postal Service will announce its final decision in a Record of Decision (ROD) at the end of October.

Once the ROD is published, the plaintiffs will probably ask for the stay to be lifted so the suits can resume. As they state in the Joint Status Report for CleanAirNow v DeJoy, the plaintiffs “will likely seek an expedited briefing schedule to allow the court to address the alleged NEPA violations before a significant number of gas-powered off-the-shelf vehicles are delivered.”

In addition to the lawsuits, the Postal Service’s fleet decision will soon come up against California’s Advanced Clean Fleets Rule, which requires fleet owners to transition their fleets to zero-emission vehicles. Other states and localities have emission laws and policies as well, and commenters argued that the Final SEIS should account for inconsistencies between these regulations and the procurement plan.

The Postal Service replied, “If any forthcoming federal or State vehicle regulations are determined to be applicable to the Postal Service’s fleet, the Postal Service will strive to comply to the extent possible given its statutory mandate to be self-supporting and to deliver to over 165 million addresses at least six days per week.”

“Striving to comply” may not be good enough, and more lawsuits may be ahead. If the Postal Service ends up being required to comply with California’s Advanced Clean Fleets Rule, it may need to devote a larger proportion of the new EVs to California than it might otherwise want to do, based on its own logistical and financial considerations. Other states may find that unfair, which will further complicate the deployment.

A wider range of alternatives

The FEIS issued back in December 2021 examined the impacts of a purchase of 160,000 new vehicles, 10 percent of which would be electric. After considerable pushback and $3 billion from Congress and the Biden administration in the Inflation Reduction Act, the USPS increased the percentage of EVs and did a supplemental EIS on the new plan.

The SEIS considers a purchase of 106,000 new vehicles. The Postal Service says it reduced the scope of the initial purchase due to its “revised procurement strategy that pursues a multiple-step acquisition process.” This new strategy will be more responsive to the Postal Service’s evolving operational strategy, technology improvements, and changing market conditions for EVs over the ten years it will take to replace the fleet.

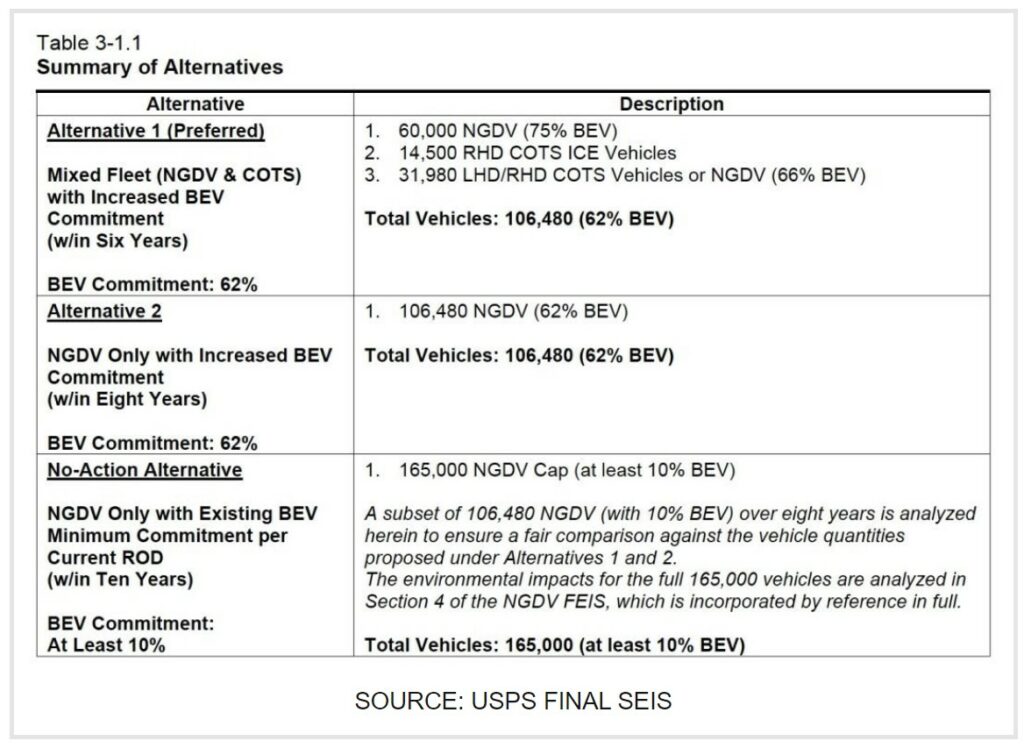

The Final SEIS considers three alternatives (the same as in the draft SEIS):

- The first alternative, which turns out to be the Preferred Alternative, involves buying 106,480 vehicles with 62 percent of them electric (65,000 EVs), with a mix of custom-built Next-Generation Delivery Vehichles (NGDVs) and off-the-shelf vehicles, purchased over six years.

- The second alternative involves 106,480 vehicles, all custom-built NGDVs, with 62 percent electric, purchased over eight years.

- The third alternative is the “No-Action” Alternative, which consists of buying only 10 percent EVs, as originally planned.

The comments on the SEIS repeatedly argued that the two alternatives to the no-action alternative were too similar and represented a failure to evaluate a reasonable range of alternatives, so a more robust analysis of alternatives should be conducted. The Postal Service replied that the two alternatives were actually very different.

More specifically, the commenters argued that the final SEIS should consider an alternative that commits to 90 or 100 percent electric vehicles.

The Postal Service did not change the alternatives at all when it prepared the Final SEIS, and it rejected the 90-100 percent recommendation for several reasons: EVs have a limited range that makes them unsuitable for many routes; the up-front cost of purchasing more EVs is prohibitive; gas-powered vehicles can be obtained at a faster pace than EVs, and there’s no need to wait for the installation of charging infrastructure.

The commenters went through each of these objections in detail, but the Postal Service was unwavering in its commitment to buy only 62 percent EVs. It did hold out the possibility that future purchases would be 100 percent electric, but refused to make a firm commitment and said it will revisit the issue when there’s more data, more experience with EVs, new technologies, and so on.

The 70-mile max

The Postal Service says it cannot deploy EVs on routes that exceed 70 miles in order to avoid the risk of running out of power mid-route. It’s not quite clear, though, how many routes this applies to.

In the SEIS, the Postal Service says fewer than 10 percent of the routes where the new vehicles will be deployed fall outside this 70-mile EV-compatible range. Earlier, in the Final EIS on the first 10-percent-EV plan, the Postal Service said approximately 5 percent of the routes are longer than 70 miles. The USPS Office of the Inspector General found only 2 percent of all the nation’s 233,000 routes were 70 miles or longer.

The commenters presented data showing that many EVs can easily go more than 70 miles, and they argued that even if 10 percent of the routes were more than 70 miles, it should be feasible for at least 90 percent of the fleet purchase to consist of electric vehicles.

The Postal Service responded by saying that the range capacity of its delivery vehicles shouldn’t be compared to that of other EVs because it has to consider a variety of delivery characteristics, including climate, topography, and stop frequency, as well as length. The Postal Service said that while it “appreciates” the analyses of other agencies, it “must make vehicle investment decisions based on its financial position and operational needs, including our determinations as to appropriate route lengths.”

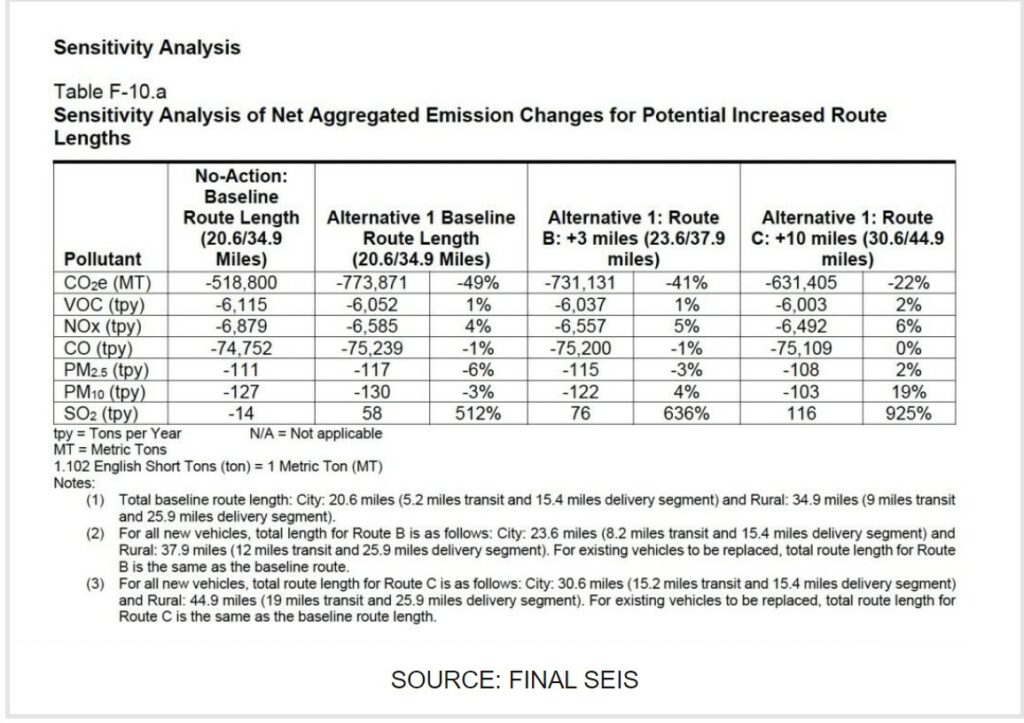

Sensitivity analysis on longer routes

Included in the SEIS is a “sensitivity analysis to identify the potential effects of increased route length on air emissions” that may result when carrier operations are consolidated to larger, centralized facilities called Sorting & Delivery Centers (S&DCs). The analysis considers two scenarios, one in which average transit distance increases by 3 miles, a second in which transit increases by 10 miles.++

The SEIS does not explain why the analysis uses these numbers, and they’re hard to understand given that the average transit for routes relocated to S&DCs will increase by about 20 miles round-trip, not 3 or 10. (Transit distance is between the delivery unit and the first and last stops on the route. There’s more about the increased distance in this post, this post, and on our S&DC dashboard.)

One possible explanation for the +3 and +10 scenarios is that the Postal Service is considering the average increase for all 106,000 routes covered by the procurement when a specific portion of these routes would go to S&DCs.

Figured that way, if 16,000 routes were deployed to S&DCs and their length increased by 20 miles, the average increase for all 106,000 routes would be 3 miles. If 53,000 routes (about half of the total) were relocated to S&DCs, the overall average would increase by 10 miles.

Perhaps this explanation for the +3 and +10 miles is incorrect, but the sensitivity analysis makes clear the obvious: Longer routes will cause more emissions and significantly reduce the benefits of electrifying the fleet.

But the Postal Service spins it otherwise and says that even with longer routes, “estimated annual aggregate emissions would still decrease relative to existing conditions for all pollutants except SO2.” While the Preferred Alternative would have a 49 percent greater CO2e reduction compared to the No-Action Alternative under the current route length scenario, it would still have a 22 percent greater CO2e reduction if the route length increased by 10 miles per day.

This sensitivity analysis barely begins to consider the full range of impacts of longer routes.

The average city route is 20.6 miles, the average rural route, 34.9 miles. For the 106,000 routes covered by the SEIS (which is 75 to 80 percent city routes), the routes average about 24 miles. For all 106,000 routes, that adds up to 760 million miles annually.

Increasing the average length by 10 miles increases the annual total by about 320 million miles — a 40 percent increase in total miles. If the S&DC plan were ultimately to encompass 100,000 routes, as advertised, the annual total would increase by 600 million miles.

These additional miles will result in more fuel and energy consumption, shorter battery life, more wear and tear on the vehicles, and more maintenance, as well as additional pollution caused by longer commutes for letter carriers going to the S&DCs in their own vehicles, most of which are not electric.

The Postal Service says that “delivery facility network optimization is not considered part of the Proposed Action analyzed in this SEIS” because the “purchase of vehicles will not itself cause any meaningful change in average route length.”

Since the plans to consolidate carriers “are still under development and are independent of the vehicle replacement program,” says the Postal Service, “this SEIS does not address the environmental impacts from this delivery facility network optimization, which the Postal Service will consider in a separate NEPA assessment if deemed appropriate.”

Given that the S&DC plan is already being implemented across the country, it appears that the Postal Service has determined a NEPA assessment is not necessary, even though the impacts of S&DCs will probably be more significant than the impacts of the new fleet.

Candidate Sites

One of the main questions about the new vehicles is where they will be deployed. Nationwide, there are 19,000 post offices with delivery units that house letter carriers and over 230,000 routes. Which facilities and which routes will see new vehicles, and how will the neighborhoods around these facilities be impacted?

To address this issue, the Postal Service focused on 414 “candidate sites” where many new vehicles would be deployed. About 84 percent of these facilities are immediately adjacent to “environmental justice communities,” so the SEIS examines how they would be impacted with respect to factors like noise (which could increase due to back-up alarms on the vehicles) and air quality (which would improve thanks to the EVs).

The SEIS identifies these “major deployment sites” only by number, which, as the commenters on the Draft SEIS complained, makes it impossible to do an independent analysis. The Postal Service refused to share the actual locations because, as explained in a footnote to the SEIS, the sites are “subject to change,” the list has not been finalized, and the locations “have not been announced publicly or within the Postal Service itself.”

The Postal Service says only that the candidate sites are larger existing facilities that would average about 100 vehicles each, and that “new vehicles would generally replace existing vehicles at the Candidate Sites; no meaningful changes are anticipated in the number of vehicles stationed at each candidate site as compared to existing conditions.”

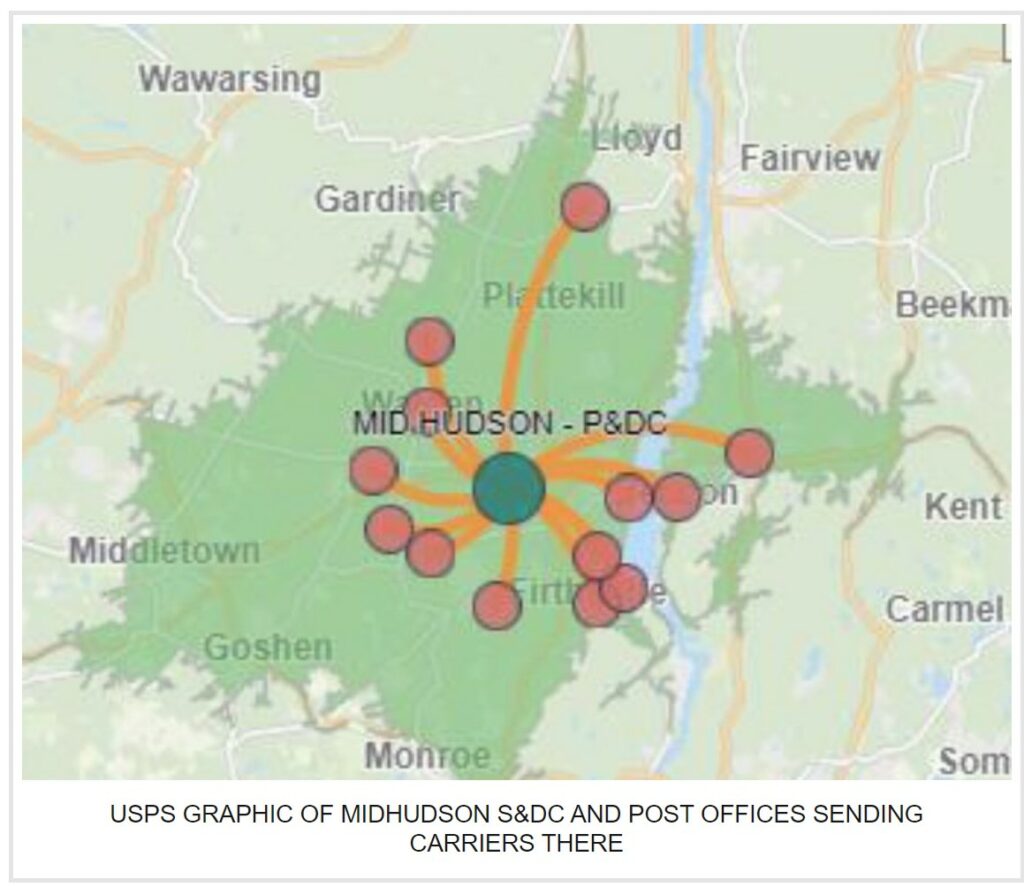

This apparently means that the candidate sites are all large postal facilities that currently average about 100 routes, and they are not the new Sorting & Delivery Centers (S&DCs) where the number of vehicles stationed will increase significantly when carrier routes are consolidated from post offices.

Since the Postal Service won’t share the list of Candidate Sites, one can only speculate. Here’s a list of potential Candidate Sites. View the list on Google Docs here.

This list consists of about 500 of the most likely deployment sites for new vehicles based on the number of carrier routes they currently host (in other words, the delivery units with the most routes). It does not contain any of the 64 facilities that have been identified as S&DCs, but it does include about 20 large processing facilities that could become S&DCs where the route count would increase. It also includes 70 leased facilities where the Postal Service may not want to install chargers to avoid issues with lessors and leases. It’s also likely that a few facilities on the list of potential sites could end becoming “spoke” post offices that send their carriers to an S&DC hub, like College Station, Texas, which sent 70 routes to the S&DC in Bryan.

In any case, if the leased facilities and P&DCs are filtered out, the list has about 415 facilities and probably represents a fair approximation of the list in the SEIS.

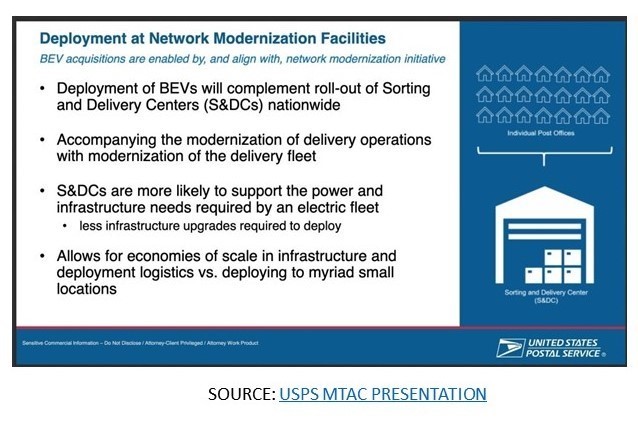

The SEIS says that the candidate sites would predominantly host EVs because of the benefits of concentrating charging infrastructure. If the 414 sites average a hundred vehicles each, they could end up hosting as many as 40,000 of the 65,000 EVs in the purchase. Those that don’t go to a candidate site would be deployed to S&DCs, which the Postal Service has been promoting as “electric vehicle hubs.”

In fact, the Postal Service has given the impression on several occasions that the first of the EVs and charging stations would be going to S&DCs, not facilities that already have a large number of carriers, as discussed in this previous post.

According to a presentation at a MTAC meeting, for example, the Postal Service explained that the deployment of EVs “will complement the roll-out of S&DCs,” which are more likely to support the power and infrastructure needs of the electric fleet without having to do upgrades.

When the Postal Service announced in February 2023 that it would be spending $260 million on 14,000 charging stations, it said the chargers would be installed at 75 locations in 2024, including Sorting and Delivery Centers. That’s just about how many S&DCs will have launched by early 2024 (as discussed here).

Wherever the EVs and charging stations are deployed, it’s clear that a large portion of the new vehicles will be going to the S&DCs. But the environmental impact of S&DCs is not even considered in the SEIS. The only consideration given to the consolidation plan involves the sensitivity analysis of the effects of longer routes on pollutant emissions.

It’s also clear that EVs and charging stations will all be deployed at the largest postal facilities — not neighborhood branches and not small town post offices. They won’t look anything like the cute images of post offices in the GAO report, which show just a couple of charging stations.

And as for making the chargers available to the public when they’re not being used by postal vehicles, the Postal Service says, “providing public charging is not aligned with our legislated mission, would provide significant operating issues (e.g., ensuring availability of parking for customers and managing charger usage and repairs), could jeopardize user safety, and increase our cost potentially without any statutory authority to generate revenue from the effort.”

The costs

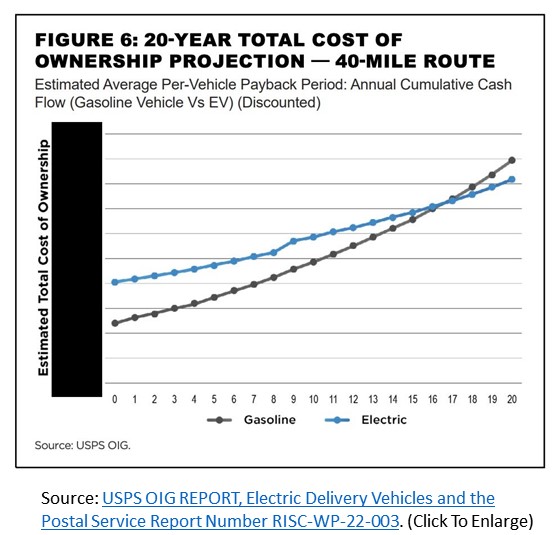

The original EIS in 2021 used a Total Cost of Ownership (TCO) model to help determine how many EVs and how many gas-powered vehicles to buy. The TCO includes not only the original purchase price but also the costs down the road, like fuel, battery life, and maintenance.

In the SEIS, however, the Postal Service shifted to up-front acquisition costs as a determining factor, thus ignoring the lower fuel and maintenance costs of EVs and the risks posed by oil price shocks over time. They pointed to an OIG report showing that for longer routes, the TCO for EVs would eventually be lower than for gasoline vehicles. Commenters also argued that using up-front costs skewed the analysis toward gas vehicles.

In response, the Postal Service explained that it shifted approaches because it doesn’t have the resources to purchase vehicles irrespective of acquisition costs and because “precise scheduling of each element of the transition to electric vehicles (e.g., acquisition and installation of chargers and training of employees must take place before BEVs arrive) is critical to ensure the Postal Service can achieve our Universal Service Mission.” Using up-front costs was therefore determined to be “more reasonable, prudent and transparent.”

The Postal Service also rejected the notion that using up-front costs “skews” the choice toward gas vehicles and claimed that if it used the TCO approach, it would be able to buy far fewer EVs. According to the Postal Service’s analysis, “higher gasoline prices did not result in EVs having a lower TCO than gas vehicles for most routes over the 20 year horizon we anticipate using these new vehicles.”

Using non-union labor

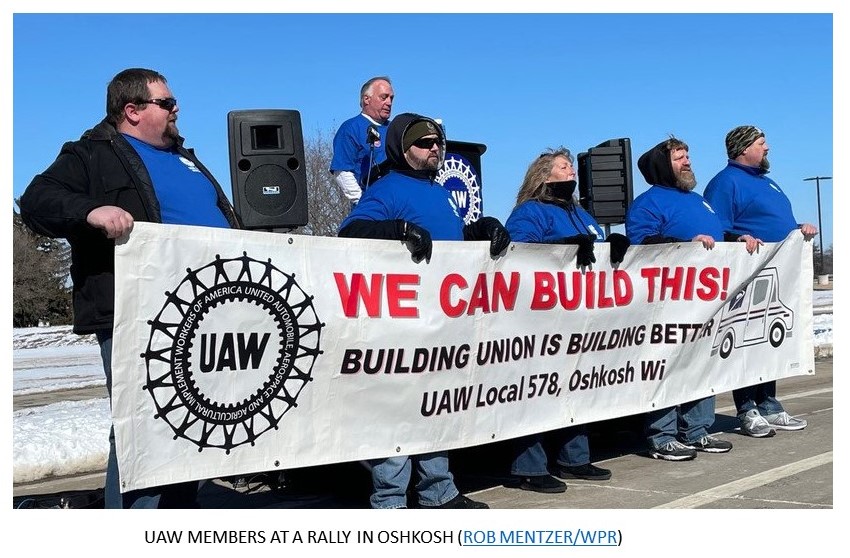

The United Auto Workers criticized the purchase plan because Oshkosh Defense has decided to manufacture the vehicles in a new facility in South Carolina using non-union labor rather than in Wisconsin with union workers.

In its comments on the Draft SEIS and its lawsuit against the Postal Service, the UAW argues that the Postal Service has a social responsibility and legal obligation under NEPA to consider all the impacts of the production of the vehicles, including the effects on workers, employment, and local economies.

“By using a non-unionized facility to build USPS’s NGDV fleet,” argues the UAW, “the agency will create a new product line essentially from scratch without many of the important safety and environmental measures that UAW would require in a collective bargaining agreement.”

According to the UAW, the Postal Service’s “approach to NEPA has been result-oriented from the start, designed to reach a predetermined outcome — as made clear in the agency’s already executed procurement order. However, the NEPA process cannot be used to rationalize or justify a decision already made by the agency.” The process should instead be treated as a serious effort to address all relevant concerns raised by the public.

The UAW also argues that the Postal Service should act in accord with the Biden Administration’s goals to promote the use of union labor, such as Executive Order 14025 on Worker Organizing and Empowerment (April 26, 2021).

In its responses to the comments on the Draft SEIS, the Postal Service says simply, “the supplier determines whether or not it will use union labor to perform under its contract… The Postal Service has no comment on the internal management or labor relations practices of its suppliers.”

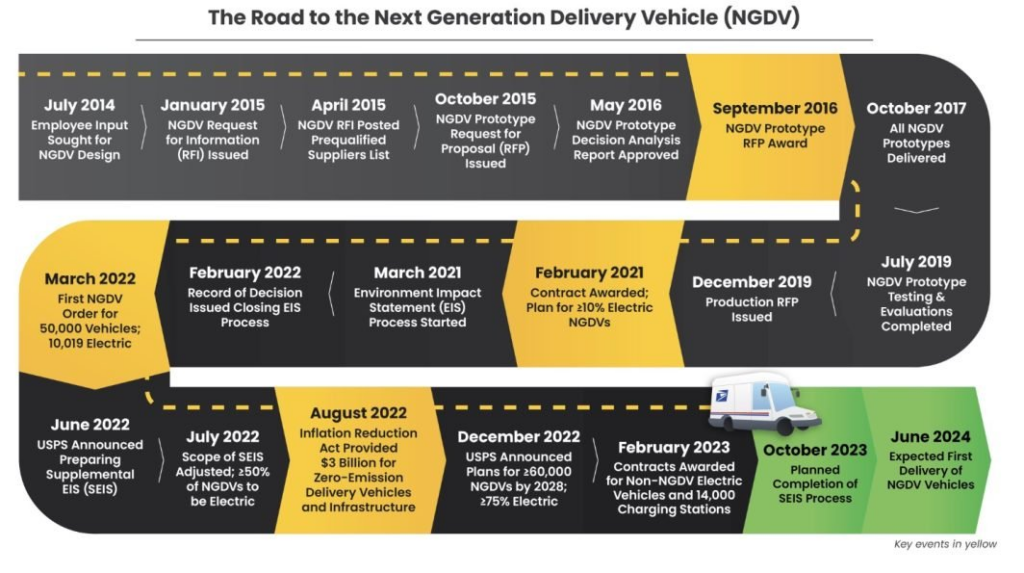

The long and winding road to a new fleet

The Postal Service began the process of procuring a new fleet back in 2014. It awarded the contract to Oshkosh Defense in February 2021, then began the EIS process the following month. Two a half years later, the Postal Service issued the Final version of the Supplemental EIS. The agency says the first next-gen delivery vehicles should arrive in June 2024.

But that’s not for certain. Given that the Final SEIS is nearly identical to the Draft version, the EPA and the plaintiffs in the lawsuits are likely to continue their effort to increase the number of EVs, and the UAW will continue the fight against using non-union labor. Whether that will slow down the delivery of the new vehicles remains to be seen.

When the Postal Service promotes the S&DC plan, it emphasizes the connections to the EV plan, but when it comes to analyzing their environmental impacts, the Postal Service wants to treat the plans as totally separate. Segmenting the plans like this may not be sustainable. As the S&DC plan comes into clearer view, the impacts of longer routes and centralizing carrier operations will raise more questions about the vehicle procurement.

— Steve Hutkins