Except for the beginning, mostly a copy and paste here. Housing is an issue in the U.S. There are not many appropriately priced house being built or used ones on the market. The same holds true for apartments. We have a lot of young families trying to figure out where to live. Then once they decide, they can not find the necessary housing much less the pricing they can afford. Now, I said it twice. Do you get the picture? The author has described the situation rather well. What makes this more troublesome is the large generation who are going out the door to oblivion in the next couple of decades has been buying up the market. Mid 2021 to mid 2022, Baby Boomers bought up 39% of the housing market, High demand, housing shortage, and the price

Topics:

run75441 considers the following as important: Baby Boomers, Hot Topics, Housing Market 2021 - 2022, James Rodriguez, Millenials, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Except for the beginning, mostly a copy and paste here. Housing is an issue in the U.S. There are not many appropriately priced house being built or used ones on the market. The same holds true for apartments. We have a lot of young families trying to figure out where to live. Then once they decide, they can not find the necessary housing much less the pricing they can afford. Now, I said it twice. Do you get the picture?

The author has described the situation rather well.

What makes this more troublesome is the large generation who are going out the door to oblivion in the next couple of decades has been buying up the market. Mid 2021 to mid 2022, Baby Boomers bought up 39% of the housing market, High demand, housing shortage, and the price goes up and others are priced out of the market,

Boomer homebuying bonanza, INSIDER, James Rodriguez

Millennials have never had it easy in the housing market. A mountain of student debt, widespread housing shortage and stiff competition from their deep-pocketed elders kept them on the sidelines longer than previous generations. Despite these challenges, the sheer size of the generation, combined with the fact that many of its members have now reached prime homebuying age, means more millennials are literally getting their foot in the door with each passing year.

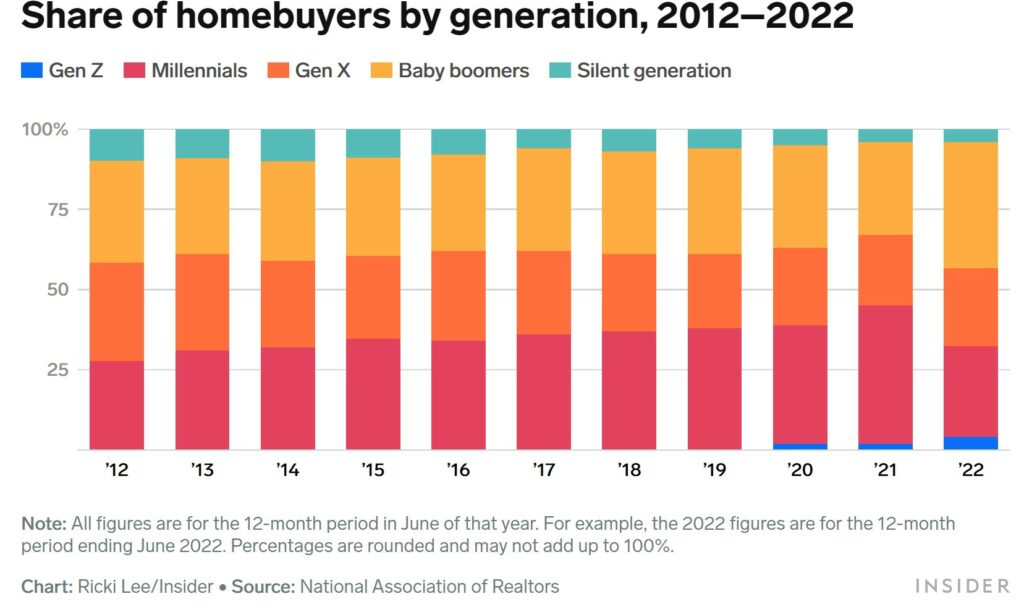

But after a decade in which the “avocado toast” generation sat atop the housing-market heap, baby boomers have suddenly and unexpectedly seized the upper hand. Between July 2021 and June 2022, boomers were the largest share of homebuyers for the first time since 2012, according to new data from the National Association of Realtors. Boomers purchased 39% of all homes that sold during that span, up from 29% the year before. Millennials, on the other hand, saw their share of the market shrink to just 28%, down from 43% the year prior.

Despite the numbers game favoring millennials, a slew of other factors conspired to allow boomers to stick it to their successors. The main thing, though, was cash. Boomers are more advanced in their careers and in many cases have already spent decades amassing home equity, making them much more likely than other generations to fork over all cash for their next property. And when bidding wars become the norm, it pays to offer a lump sum.

While the sudden reversal is a sign of the financial strength of boomers, it also underscores the bleak prospects for millennials and the growing divides within the generation. For better or worse, homeownership is the most popular form of wealth building for most American households. When millennials are forced to delay their home purchases and continue renting, they miss out on years they could have spent stacking up equity. Millennial homebuyers are also more likely than older cohorts to use financial help from friends or family, further tilting an already uneven playing field toward the “haves” who are able to tap resources from previous generations.

The housing market is not a generation-versus-generation cage match. But at a time when there aren’t enough homes to go around and homeowners rely on rising property values to build wealth, it can feel like the prosperity of one generation has to come at the expense of another. And in this battle between youth and wisdom, it appears gray-haired house hunters are taking one last chance to trump their less-seasoned successors.

Cash is king

Millennials have been an economic Eeyore for years. The Great Recession threw a wrench in their early careers, and the slow start meant that, compared to previous generations, they had a worse chance of making more than their parents. In the years that followed, builders didn’t produce enough homes to meet the looming wave of demand from younger buyers. Between 2010 and 2019, homebuilders started roughly 21,000 single-family homes per 1 million people each year, barely half as much as they were building in each of the three decades prior.

But by 2019, millennials were getting on better footing: The long recovery from the recession meant the labor market was in a strong place, savings were picking up, and they overtook baby boomers as the largest living generation, with a population of 72.1 million people. Though millennials were delaying traditional life milestones and finding themselves with less wealth than previous generations, they were buying more homes than ever.

That was all flipped on its head during the pandemic. The long-gestating undersupply of housing, near record-low mortgage rates, and a suddenly footloose workforce sent home prices soaring — and the competition to find a new place to call home became fierce. A generation that should have been reaching its homebuying sweet spot instead fell further behind.

Jessica Lautz, the deputy chief economist and vice president of research for the National Association of Realtors, told me . .

“There are more millennials than anyone else. So the fact that they are now trailing behind the baby boomer population just speaks to the difficulty of the housing market today.”

Boomers, meanwhile, came of age during years of healthy housing construction. In the 1960s and 1970s, homebuilders averaged roughly 50,000 housing starts per 1 million people each year, well more than double the rate during the 2010s, according to the National Association of Home Builders. This building boom helped drive homeownership — more than half of boomers owned a home by the age of 30, compared with 48% of Gen Xers and 42% of millennials.

Boomers have also sustained their homebuying activity longer than their predecessors, who were more likely to settle into one home. The share of recent buyers who were 60 years and older grew 47% from 2009 to 2019, which means millennials “face more competition from their parents’ and grandparents’ generations than their predecessors did,” a Zillow study found.

When the pandemic rolled around, boomers were able to leverage their economic advantages to jump back into the market like never before. Cash purchases have been on the upswing since the beginning of 2021 — this past October, roughly a third of homebuyers paid with all cash, the highest share since 2014, according to Redfin. The pivot to cash gave boomers a leg up, since they had plenty of home equity to tap.

Over the past decade, the average homeowner accrued roughly $210,000 in equity, according to the NAR. And as the typical down payment for a home more than doubled during the pandemic — peaking at $66,000 in May 2022, according to Redfin — the ability to use cash savings or the profits from a home sale benefited more senior buyers. During the NAR’s latest survey period, 51% of older boomers, aged 68 to 76, paid with all cash, compared to just 6% of buyers 32 years and younger. That dynamic, Lautz told me, has played a significant role in the rise of older buyers. She said;

“If they’re not paying all cash, they can put down such a large down payment that they’re able to compete in a very successful way.”

A new era

While millennials are primarily buying homes in an attempt to get on or move up the housing-wealth ladder, boomers’ recent moves were primarily motivated by the desire to slow down. The cohort, who range in age from 58 to 76, told the NAR that their moves were triggered by an urge for a smaller property or to be closer to friends and family after retirement. Boomers typically moved the farthest distance of any generation — a median of 90 miles for young boomers, and 60 miles for older member. Lautz said.

“They’re finally at a point in their life where they can purchase their retirement property.”

Given the fact that many of these moves were made with the intent of settling down, it’s hard to tell if boomers will maintain their dominance or if this is a blip from an unusually dysfunctional year. When I asked Lautz to weigh in on the comeback’s sustainability, she hesitated to make a prediction. Lautz . . .

“Is this a lasting trend, or did boomers make their trade last year and now they’re set in their retirement properties? It’s hard to say right now.”

A lot has changed in the housing market since the NAR’s survey period. The competition for homes has slowed considerably, thanks largely to mortgage rates that have risen from historically low averages of less than 3% during the pandemic to about 6.4% as of late March. Less competition is especially good for millennials, as the past few months have shown: More first-time buyers appeared to be winning out on homes, Lautz said. But these kinds of buyers are also much more likely to take on loans, and therefore disproportionately affected by higher borrowing rates. Once again, boomers are more insulated from the whims of the market than their younger counterparts. Lautz.

“While first-time homebuyers suddenly saw their affordability hurt by the rise in interest rates, people who are paying all cash didn’t. They’re not going to have the same challenges.”

Even if nationwide home prices continue to slide, they’ll likely remain dramatically higher than they were before the pandemic. And baby boomers have already shown a desire to stay out of nursing homes longer than their predecessors, meaning they’ll probably play an active role in the housing market for years to come. In a housing market of “haves” and “have nots,” equity-rich homeowners have the edge over hopeful first-time buyers. That’s not changing anytime soon.

Millennials know that they have time on their side, since boomers will eventually age out of the market entirely. But playing the waiting game may not be the best strategy — there are already signs Gen Z is coming up right behind.