Morning . . . One other factor I believe you may have missed (too many factors). The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not pay for itself over the last 10 years. Just a small matter of it passing using Reconciliation which insists it pay for itself (being redundant here). The repeal of it impacts those in the upper 10% (or more) of the taxpayers and more so the 1 percenter who make up a million (taxpayers) or slightly more taxpayers having income far greater than the lowest ten percenter. Lest we forget, corporations, the management, and their stockholders have much to lose if the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is repealed. It is not just high rollers such as Jamie getting nervous. It is Corporations and all the stockholders domestic and abroad who

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: 2017 tax breaks, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

Morning . . .

One other factor I believe you may have missed (too many factors). The 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act did not pay for itself over the last 10 years. Just a small matter of it passing using Reconciliation which insists it pay for itself (being redundant here).

The repeal of it impacts those in the upper 10% (or more) of the taxpayers and more so the 1 percenter who make up a million (taxpayers) or slightly more taxpayers having income far greater than the lowest ten percenter. Lest we forget, corporations, the management, and their stockholders have much to lose if the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act is repealed.

It is not just high rollers such as Jamie getting nervous. It is Corporations and all the stockholders domestic and abroad who have much to lose. But then again, this tax break should never have happened. Party line vote with 12 Repubs in the House joining Dems plus one Repub Senator.

The corporate tax rate would revert back to 35% from 21% (CEPR or Brookings). Jamie would lose some of his bonus going forward.

I believe this is where the influence to sh*t-can Biden is coming from today.

In the run-up to the law’s passage, Trump and his leading economic advisers claimed that the benefits of the bill would trickle down, resulting in substantial gains for U.S. workers and their families and for the U.S. economy as a whole.2 Critics at the time argued that these claims were unlikely to come to pass.3 Now, more than six years later, there is little evidence that the law’s costly corporate tax cuts delivered promised growth or improved well-being for the vast majority of the nation’s workforce. Instead, the law provided the largest tax cuts to the wealthy and profitable corporations, exacerbated inequality, and eroded revenues that could otherwise have been used to address national priorities.

The upcoming debate in Congress over the future of the law’s temporary changes to personal and estate tax provisions provides lawmakers with the opportunity to revisit the law’s corporate changes. This issue brief reviews the evidence showing that the 2017 corporate law changes failed to deliver promised benefits and should be reformed.

An explanation by Jean Ross of CAP20

~~~~~~~

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Failed to Deliver Promised Benefits

by Jean Ross

CAP20

Benefits of the 2017 tax changes were overwhelmingly skewed toward the wealthy

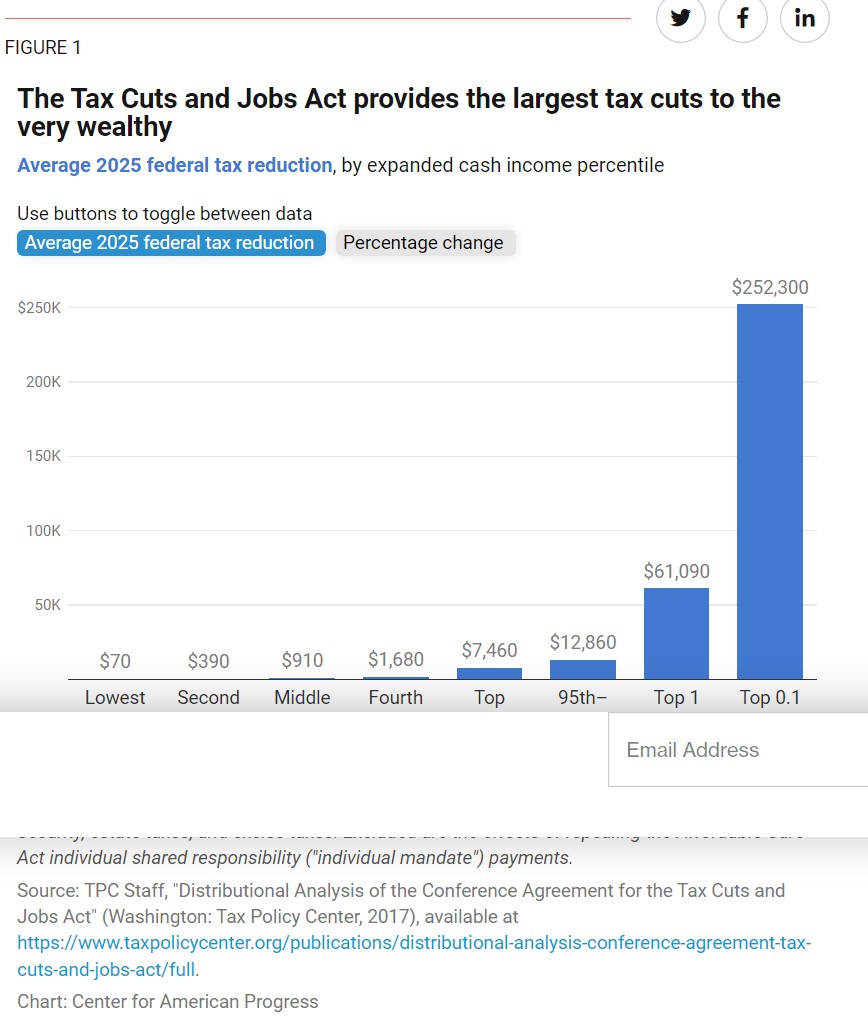

The 2017 law changes disproportionately benefited the highest-income households. In 2025—the last year before the temporary changes to the personal income and estate tax provisions expire—households in the top 1 percent of the income distribution will receive an average tax cut of $61,090.4 In contrast, those in the middle quintile of the distribution will receive an average reduction of $910, while those in the lowest quintile will receive, on average, just a $70 reduction.

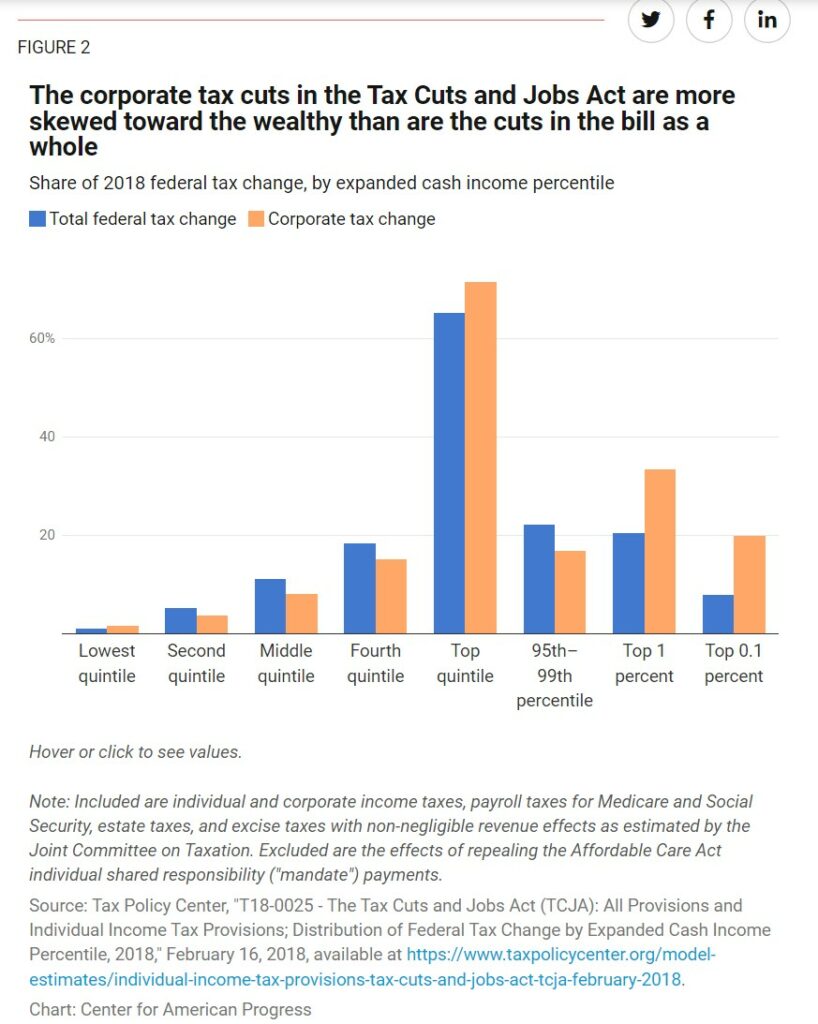

The benefits of the corporate tax reductions were even more skewed toward the wealthy than those of the bill as a whole.5 The top 1 percent of the income distribution received a full third of the corporate tax reduction but 20 percent of the reduction from all of the measure’s provisions. (see Figure 2) The middle quintile of the income distribution received 8.2 percent of the benefit of the business reductions and 11.2 percent of those from the bill as a whole.

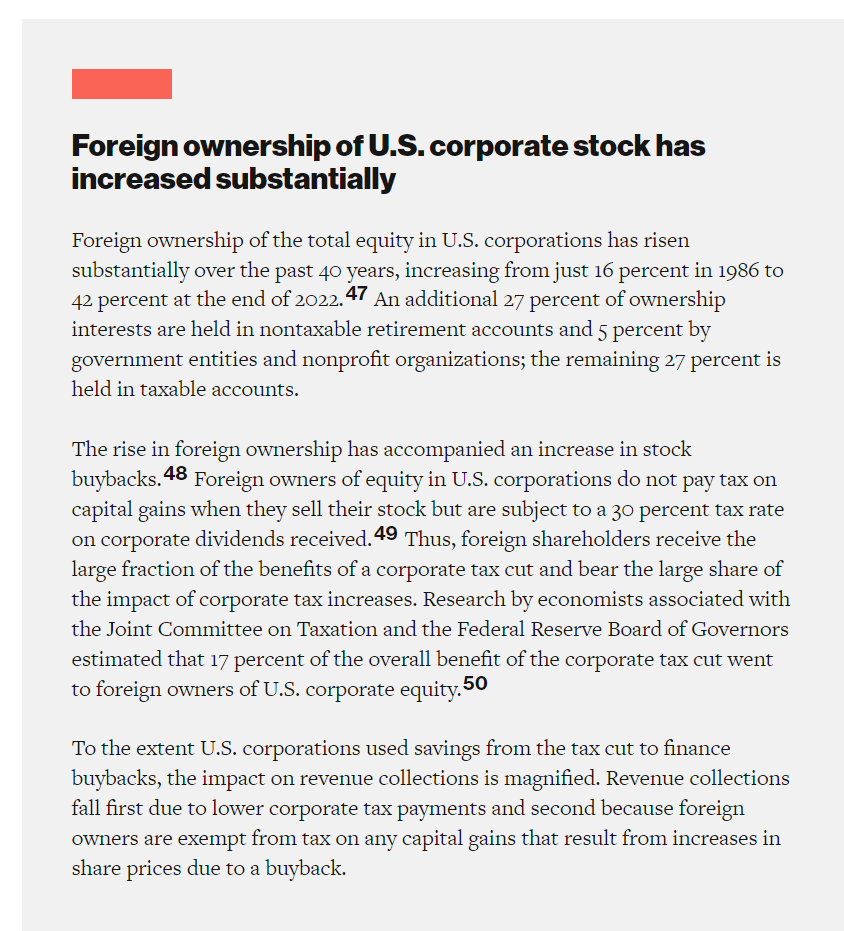

Foreign owners of equity in U.S. corporations also benefited from the measure’s business tax cuts. New research by economists at the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Federal Reserve Board of Governors estimates that slightly more than $1 out of every $6—17 percent—of the gains from the corporate tax cuts flowed to foreign owners.6

Big Surprise . . . The TCJA’s corporate rate cuts failed to trickle down to ordinary workers

During debate over the tax bill, Trump administration economic officials claimed that “the average household would, conservatively, realize an increase in wage and salary income of $4,000” from the TCJA’s combination of a lower corporate tax rate and the ability to immediately write off nonstructure investments.7 Kevin Hassett, the chair of the Council of Economic Advisers at the time of the bill’s passage, went even further and predicted that average household income could rise as much as $9,000 per year as a result of the tax package.8 While critics at the time expressed doubts about these claims, proponents argued that the benefits of the tax cut would trickle down to ordinary workers as a result of businesses increasing investment; this, in turn, would lead to higher productivity and higher wages.9

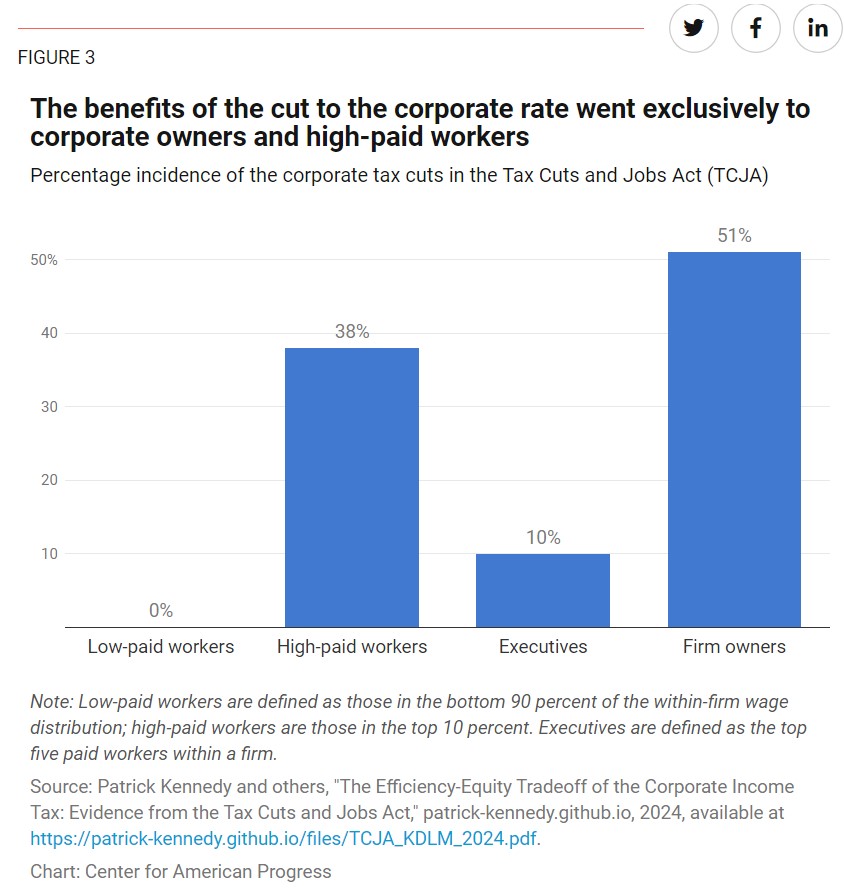

Important research first published in 2022 by authors affiliated with the Joint Committee on Taxation and Federal Reserve Board that matched corporate tax returns with information returns for firms’ shareholders and workers found that the benefits of the TCJA’s corporate tax reductions did not trickle down.10 In fact, the study found that “earnings do not change for workers in the bottom 90% of the within-firm distribution, but do increase for workers in the top 10%, and increase particularly sharply for firm managers and executives.” The economists further noted that executive pay hikes were only weakly correlated with sales, profits, or sales growth and “are not clearly linked to stronger firm performance.”

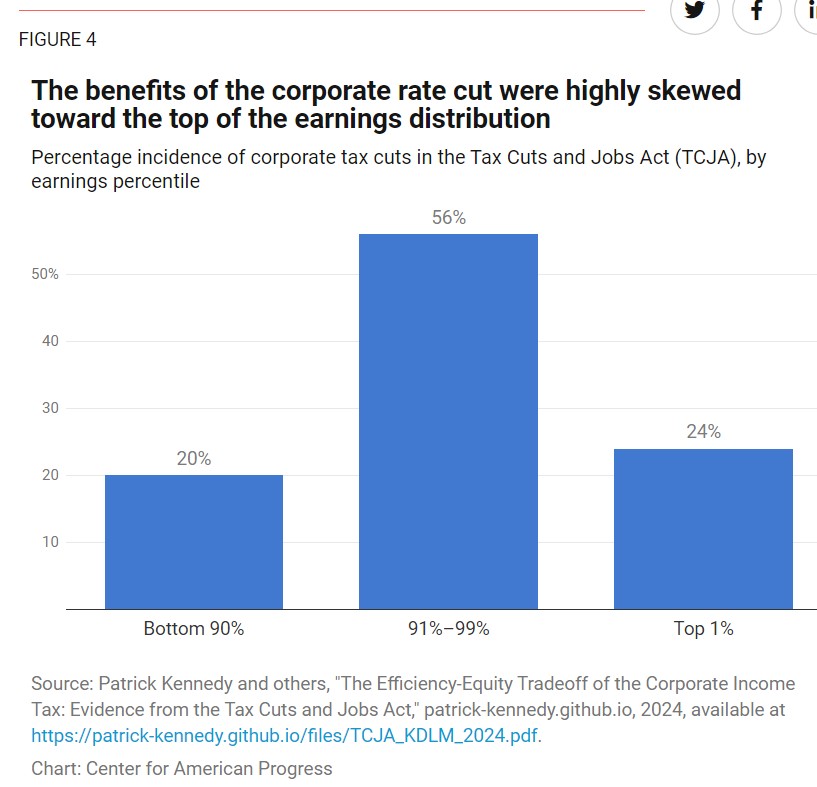

Even after taking into account the fact that some low-wage workers may be firm owners, the researchers concluded that the benefits of the TCJA’s tax changes were overwhelmingly skewed toward the top of the earnings distribution, with 24 percent of the gains from the tax cut going to the top 1 percent and just 20 percent going to the bottom 90 percent.

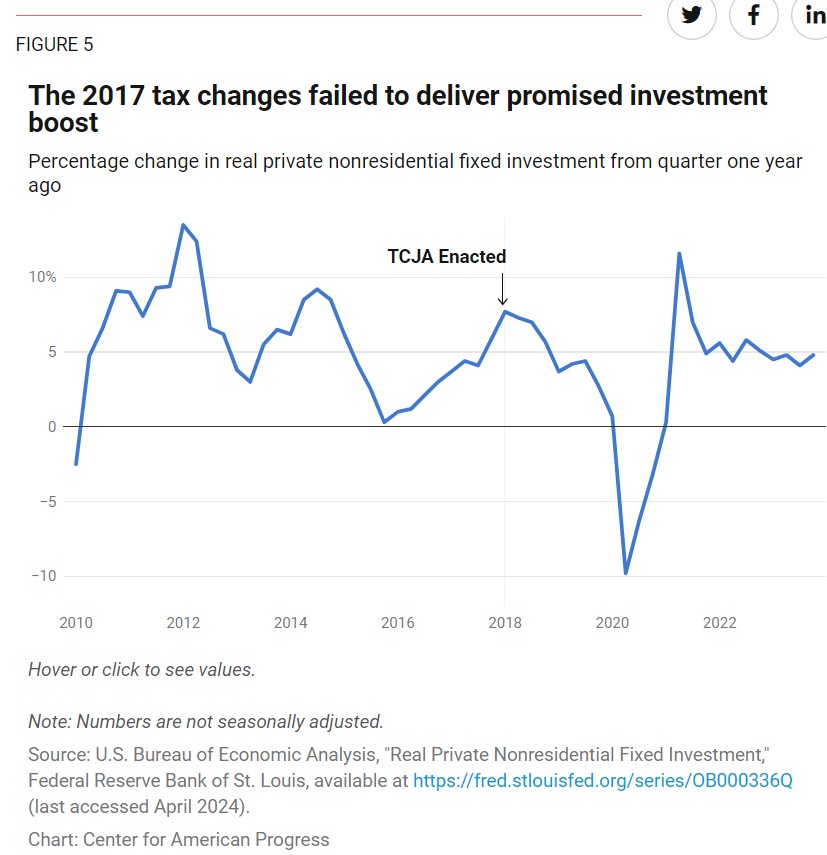

Corporate investment slowed immediately following enactment of the TCJA

Proponents of the corporate tax cut argued that businesses would invest amounts saved in new equipment, facilities, and their workforce, thereby fueling economic growth.11 Yet this promised investment boom failed to occur. Although investment rose following enactment, it initially did so at a lower rate than proponents’ claims implied and then slowed before turning around in the wake of substantial public investments made to stem the impact of the pandemic-induced recession.12

A 2019 report by International Monetary Fund (IMF) researchers examined the impact of the TCJA on investment and concluded that: 1) “the overall strength in aggregate demand appears to have been the primary driver of the rise in business investment since 2017,” and 2) “the investment response to the TCJA thus far has been smaller than would have been predicted based on the effects of previous U.S. tax cut episodes.”13 The IMF researchers further concluded that increased corporate market power has dampened the behavioral response to corporate tax cuts, noting that “a cut to the corporate income tax rate would increase post-tax monopoly profits but induce a smaller behavioral response in production and investment decisions.” This analysis suggests that additional corporate tax cuts would likely be passed to shareholders, rather than spark investment.14

Other analysts’ findings echo the IMF study. The Congressional Research Service notes:

Although investment grew significantly, the growth patterns for different types of assets do not appear to be consistent with the direction and size of the supply-side incentive effects one would expect from the tax changes. This potential outcome may raise questions about how much longer-run growth will result from the tax revision.15

More recent research by Harvard economist Gabriel Chodorow-Reich and colleagues found evidence of a modest increase in capital investment after passage of the TCJA.16 However, Chodorow-Reich’s estimated long-run increase is substantially lower than that predicted by the TCJA’s proponents.17 Former Joint Committee on Taxation economist Patrick Driessen has questioned whether, due to methodological issues, Chodorow-Reich and colleagues overestimated the TCJA’s boost to investment.18

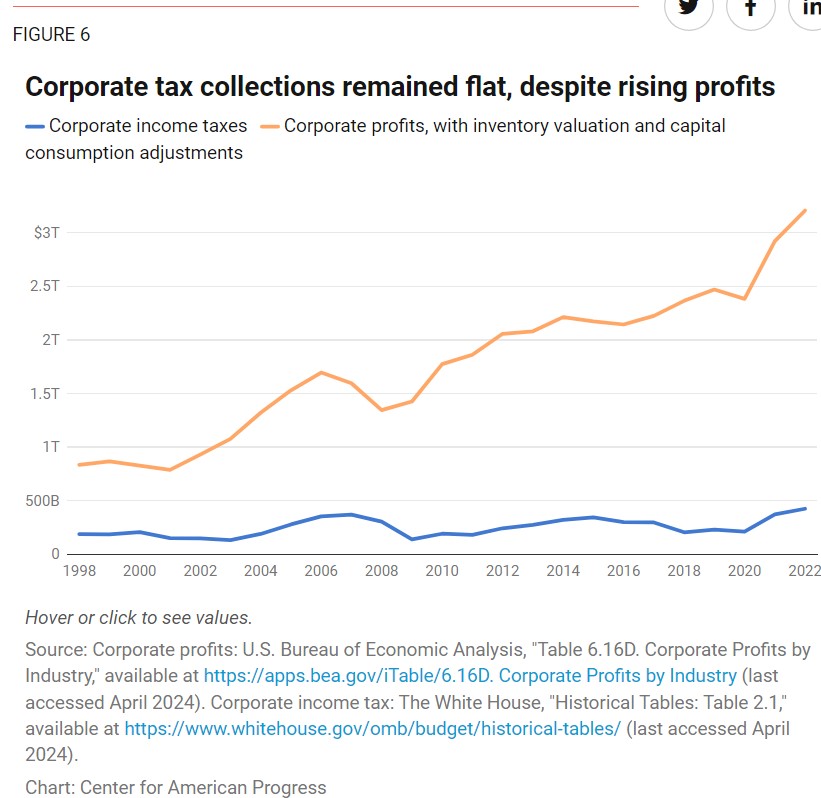

The 2017 tax cuts have not paid for themselves

Echoing long-standing claims made by conservative economists, Steven Mnuchin, secretary of the Treasury during the Trump administration, repeatedly claimed that the tax plan would pay for itself.19 In fact, the 2017 changes, taken as a whole and consistent with other tax reductions, reduced federal tax collections in the first three years after enactment (2018–2020). 20Corporate tax collections have remained relatively flat, despite profits increasing significantly after a dip in 2020 due to the COVID-19 pandemic recession. (see Figure 6)

Several recent studies examined the extent to which increases in economic activity caused by the tax cuts offset the revenue loss attributable to the direct result of the tax cut. They found that these so-called dynamic effects offset only a small fraction of the total cost of the measure. A study by Chodorow-Reich and colleagues finds that “total dynamic corporate revenue is negative over the first 10 years and remains below 1% of pre-TCJA revenue thereafter.”21

In the long term, they note that increased personal income taxes will offset some of the loss, but the measure would still “leave a decline of roughly one-third of pre-TCJA tax revenue.” The previously discussed research by authors affiliated with the Joint Committee on Taxation and the Federal Reserve Board reached a similar conclusion, estimating that after taking into account behavioral changes of firms and their owners, corporate tax revenues declined by 85 cents for each $1 of initial marginal reduction.22 In other words, increases in investment paid for just 15 cents of every dollar lost due to the tax cuts.

The TCJA’s business tax changes permanently reduced federal revenues

Because the corporate tax changes nowhere near paid for themselves, the law permanently and substantially reduced federal revenues relative to what they would have been in its absence. Changes to individual and estate tax provisions initially accounted for about three-quarters of the bill’s initial 10-year cost, while business tax provisions—including restructuring how the United States taxes multinational corporations—made up the remainder.23 This, however, understates the long-term impact of the changes since a one-time “transition tax” offset a part of the initial cost, while the revenue loss due to the permanent provisions continues.24

The decision to make the law’s changes to individual and estate taxes temporary while making those for business permanent was driven by the Senate’s budget rules and the need to keep the cost of the bill as a whole below a specific target during the 10-year scoring period.25 Cognizant of the lack of public support for deep corporate tax cuts, former Rep. Paul Ryan (R-WI) recently noted the reason the House made the business tax cuts permanent when he was speaker: “We made temporary what we thought we could get extended; we made permanent what we thought might not get extended that we wanted to stay permanent.”26

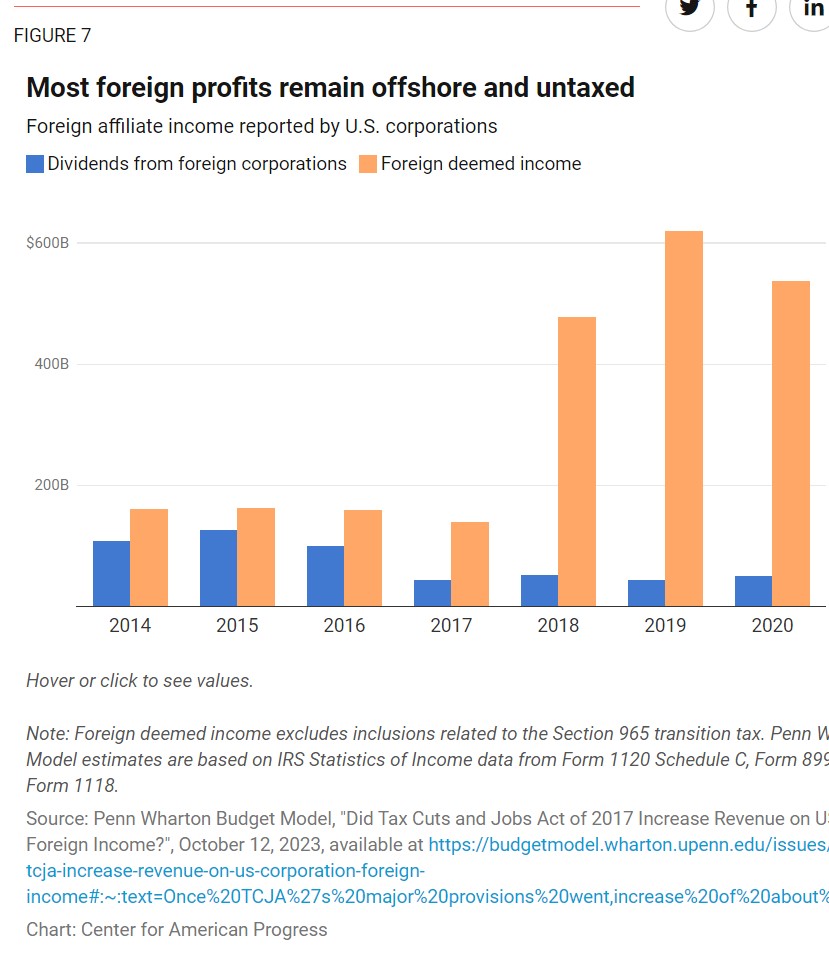

The TCJA failed to result in the onshoring of profits held overseas

At the signing ceremony for the TCJA, President Trump claimed that the law would “bring back probably $4 trillion from overseas. Nobody knows the exact number, but it’s massive. It will be over $3 trillion; it could be $5 trillion.”27 This has not happened: An analysis by University of Pennsylvania Wharton School researchers found that dividend payments made by foreign affiliates to their U.S. parent corporations fell, rather than rose, beginning in 2017,28 while so-called deemed foreign income—income held offshore but reported for U.S. tax purposes and taxed at the lower rate established by the TCJA—rose.29

Moreover, the 2017 changes only modestly, at best, reduced the share of foreign profits shifted to low-tax jurisdictions. Research by economist Gabriel Zucman and colleagues found that in the first four years following the enactment of the tax changes, the share of foreign profits earned by U.S. multinational corporations that was shifted to tax havens stayed relatively constant and was substantially higher than that of non-U.S. multinational corporations.30 In separate research, Zucman and colleagues found that overall, the share of U.S. multinationals’ profits booked offshore fell by about 3 percentage points to 5 percentage points, to 27 percent.31 The authors summed up the 2017 law’s impact on profit shifting as “relatively small,” saying that while a few firms made significant shifts, “the global allocation of profits by US firms appears to have changed relatively little overall.”32

These findings are consistent with those of Kim Clausing, a UCLA School of Law professor and former Treasury Department official.33 Clausing found that the share of income that U.S. multinational corporations booked to seven major tax havens immediately after enactment of the law was identical to that in the five years prior to enactment. Subsequently, the share modestly declined to 56 percent in 2022, in contrast to an average of 61 percent from 2013 to 2017.34 Clausing projects that in the long run, the TCJA’s minimum tax—the global intangible low-taxed income tax (GILTI)—will modestly increase the U.S. tax base by $17 billion to $30 billion, a tiny fraction of the trillions of dollars that Trump had projected.35

The trade deficit has widened, not narrowed, since the passage of the TCJA

In advocating for the passage of the tax measure, then CEA Chair Hassett claimed that a “corporate tax cut to 20 percent would dramatically reduce the trade deficit and increase GDP accordingly.”36 In fact, after remaining essentially flat from 2018 to 2019, the trade deficit has widened and continues to be much larger than it was in the five years prior to the passage of the tax bill.37 Although pandemic-related factors—including the more rapid U.S. recovery relative to our trading partners—contributed to the wider gap, here too, corporate tax reductions failed to narrow the trade gap.38

Stock buybacks increased significantly in the wake of the tax cut

That the tax cut did not boost wages and had a modest impact on investment raises the question of what corporations did with their windfalls. A substantial fraction of corporations’ savings went toward repurchasing their own stock, thus boosting share prices and the wealth of investors. Corporations have two ways to distribute profits to shareholders: by paying dividends or by repurchasing the firm’s stock. 39

Before 1980, publicly traded companies primarily paid out as dividends profits not needed to finance investment.40 The use of stock buybacks has increased—more slowly at first, but with a substantial uptick in recent years and a spike immediately following the 2017 tax changes. Researchers at the IMF examined how firms used increased cash flow from their tax savings and found, “Only about 20 percent of the incremental cash outflow post-TCJA went towards capital expenditure or R&D while the rest went towards share buybacks, dividends, and other activities.”41 A more recent analysis by the Institute on Taxation and Economic Policy found that, from 2018 to 2021, S&P 500 companies spent more on buybacks than capital investment.42

Stock buybacks, in contrast to dividends, allow investors to avoid immediately paying taxes on amounts received.43 Moreover, they can hold onto appreciated shares and choose when—and, often, whether—to pay taxes at all.44 Buybacks provide substantial benefits for foreign investors, who are not subject to tax on capital gains but who do pay taxes on dividends paid out by U.S. corporations.45 A recent study by the Tax Policy Center estimated that foreign shareholders would pay $0.145 in tax on each dollar received as a divided, but no tax on the gains generated by a dollar used for a stock buyback.46

Conclusion

An important body of evidence shows that the corporate tax changes in the 2017 Tax Cuts and Jobs Act failed to produce promised investment or wage increases for the vast majority of U.S. workers. The law did, however, significantly reduce corporate tax collections, diverting resources from public investment to the pockets of wealthy shareholders, executives, and high-paid workers.

The Tax Cuts and Jobs Act Failed To Deliver Promised Benefits – Center for American Progress