– by New Deal democrat Over the weekend Harvard econ professor Jason Furman suggested that the Fed funds rate is not very restrictive: “As inflation has come down the real Federal funds rate has risen and is now the most restrictive it has been this cycle, a point that Austin Goolsbee has emphasized a number of times . . . That is not the way I would look at it. The rates that matter for the economy are long rates. and expected inflation over, say, the next decade has not changed that much. So, the real mortgage rate, for example, is restrictive but not increasingly so.” Let’s take a look. First, here is the historical look at the real Fed funds rate, i.e., the nominal rate minus the YoY inflation rate. Since it is currently just under

Topics:

NewDealdemocrat considers the following as important: Education, Real Interest Rates, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes Time for Senate Dems to stand up against Trump/Musk

– by New Deal democrat

Over the weekend Harvard econ professor Jason Furman suggested that the Fed funds rate is not very restrictive:

“As inflation has come down the real Federal funds rate has risen and is now the most restrictive it has been this cycle, a point that Austin Goolsbee has emphasized a number of times . . . That is not the way I would look at it. The rates that matter for the economy are long rates. and expected inflation over, say, the next decade has not changed that much. So, the real mortgage rate, for example, is restrictive but not increasingly so.”

Let’s take a look.

First, here is the historical look at the real Fed funds rate, i.e., the nominal rate minus the YoY inflation rate. Since it is currently just under 2.4% higher than inflation, I subtract that so the current rate shows at the zero line below:

Indeed the current real Fed funds rate is the most restrictive since just before the Great Recession. Beyond that, it is also more restrictive than during most of the 1960s and 1970s. Only during the 1980s and the latter part of the 1990s was it consistently higher. We’ll circle back to this further below.

Also, note that interest rates – not so coincidentally – were only as restrictive or more restrictive than their current levels shortly before recessions during the 1960s and 1970s, as well as the 2000s.

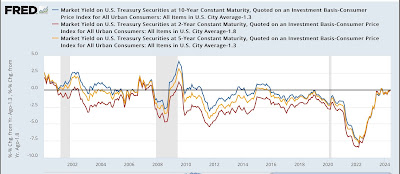

But what about compared with longer rates? Here is the same graph, again normed to zero at its current readings for the real 10 year treasury rate (blue), real 5 year Treasury rate (gold), and real 2 year Treasury rate (red) since the turn of the Millennium:

The two year real rate is almost as restrictive as the real Fed funds rate over this nearly 25 year period. Further, while the 5 and 10 year real rates are *relatively* less restrictive, they are still more restrictive than at almost any time in the past 10 years, and about average for the 15 years before that.

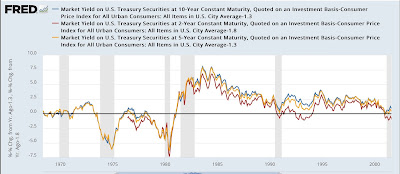

Here is the same graph for the period of the 1960s through 1990s for which data is available:

Longer term real rates are less restrictive than at almost any point in the 1980s and 1990s, but about average for the 1960s and more restrictive than most of the 1970s.

So the conclusion is that longer term real rates are generally more restrictive than at most times in the past 25 years, and about average for the last 40 years of the 20th century.

Which isn’t that helpful.

For forecasting purposes, there are two more important points.

1. The ECRI method that uses nominal long term bond rates as one of their four indicators that goes into their ”long leading index” does not make use of the yield curve. Rather, it asks whether long rates are higher or lower than they have been previously in the expansion. We know that rates are higher than they were before 2023, but have been roughly flat since then.

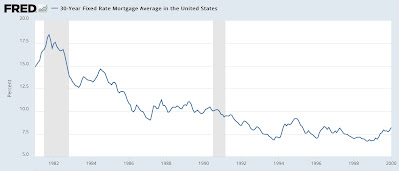

2. Now let’s circle back to the 1980s and 1990s. What was important during both of those very long expansions is that rates, although high in both nominal and real terms, *trended lower.* For example, here are mortgage rates in the 1980s and 1990s:

One of my top-line forecasting systems is based on the fundamentals of consumer behavior. Consumers can get more money to spend via higher real wages. Or an asset, like stocks or real estate equity, can appreciate in value and be cashed in. Or the interest rates servicing those loans can go sufficiently lower to allow for refinancing, thus freeing up more cash for spending.

In the 1980s and 1990s, interest rates, especially mortgage rates, very frequently made new lows. Thus even those in real terms rates were restrictive, they were *less* restrictive generally than one or two years before. Consumers refinanced, and spent the freed-up cash. It was only when no new rates were established for 3 years, and other assets stopped appreciating, that recessions occurred.

Currently we have higher real rates than at almost any time in the past 10+ years, at a level of restrictiveness equivalent to before recessions in the 1960s, 1970s, and 2000s, and long term rates that have not made new lows in 3 years.

In other words, the refinancing spigot has been shut off. If stock prices, real estate prices, and real wages stop appreciating – which they very importantly have *not* at the moment – the economy is very vulnerable to a turndown.

The Bonddad Blog

A Longgg Time Series of Safe Real Interest Rates, Angry Bear, Robert Waldman