I had presented Part I and Part II a while back. Part III was difficult to present in a piece-meal way so for now I have set it aside. What is interesting about Part IV is I can beak it apart into segments, still maintain the flow of informatio, and present it in a logical manner. Bear with me. By the time we get to the end, I believe you will be able to piece this together too. In Part IV . . . What Antonio is doing in Part IV is laying the foundation for the question asked: Are Drug Companies Alone Responsible for the Prices We Pay for Medicines? He intends to break it down. I intend to break it down further for Angry Bear. Money from Sick People Part IV: Paying a Premium for Drug Pricing Irregularity, 46brooklyn Research, Antonio Ciaccia

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: 46Brooklin Research, drug pricing, Healthcare, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Joel Eissenberg writes RFK Jr. blames the victims

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

I had presented Part I and Part II a while back. Part III was difficult to present in a piece-meal way so for now I have set it aside. What is interesting about Part IV is I can beak it apart into segments, still maintain the flow of informatio, and present it in a logical manner. Bear with me. By the time we get to the end, I believe you will be able to piece this together too. In Part IV . . .

What Antonio is doing in Part IV is laying the foundation for the question asked: Are Drug Companies Alone Responsible for the Prices We Pay for Medicines? He intends to break it down. I intend to break it down further for Angry Bear.

Money from Sick People Part IV: Paying a Premium for Drug Pricing Irregularity, 46brooklyn Research, Antonio Ciaccia

One of the principal problems in trying to understand drug prices is the policymakers have not decided what they want drug pricing policy to actually accomplish (we recently raised this point in our review of May 2024 drug pricing changes). Without a guiding principle or philosophy to act as a beacon for policy end goals, drug prices may be experienced across any number of potential paradigms and serve many potential goals – which often results in many drug prices for the same product. In other words, the observations of price discrimination in the drug supply chain has become a feature, not a flaw, within the U.S. healthcare system.

We know drug prices – at least the prices experienced by the end payer – are not set in accordance with the price a pharmacy pays to acquire those medicines. In the landmark Rutledge v PCMA decision, the U.S. Supreme Court put this fact out there relatively simply, succinctly, and in a unanimous manner by stating,

“The amount a PBM ‘reimburses’ a pharmacy for a drug is not necessarily tied to how much the pharmacy paid to purchase that drug from a wholesaler.”

We struggle to think of other industries where the provider of a product (i.e., the pharmacy) would have such little say in establishing prices in relation to the products it is offering and their corresponding underlying costs (and yet that is what we know happens with drugs). That is not to say it doesn’t happen, just that our perception is that when a grocer wants / needs a higher price for milk they raise the price for milk, when a pharmacy wants / needs a higher reimbursement to cover their costs they . . . well, we’re not sure what they can do immediately to improve their price like grocers or others can do (which is the point we’re trying to make). We also know that drug pricing is more variable (i.e. there are many prices for the same product) than a single manufacturer’s price point could possibly yield.

Undoubtedly, the price of a medication starts with a manufacturer, but it certainly doesn’t end there – nor can it be completely understood by just the manufacturer price point. If the price paid for a medicine was solely derived by the price set by the manufacturer, then everyone’s pricing experience would be consistent.

But it isn’t.

That fact does not stop some from claiming that drug manufacturers, and drug manufacturers alone, are responsible for drug pricing. Conversely, it doesn’t stop the same groups from claiming they alone are working to lower drug prices. Such simple views on drug pricing should be rejected, as they are not founded in the facts. And to help explain why, today we demonstrate just how all-over-the map U.S. drug prices are by revisiting the prices of insulins in the aftermath of the big insulin drug list price cuts that took place at the start of the year.

Some Background

Insulin has been the poster child of drug pricing dysfunction for decades. Unsurprisingly, insulin has been a frequent flyer in our Money From Sick People series, as a lot of effort has been directed at trying to understand how a life-saving medication (people with Type 1 Diabetes will die without insulin) can for some be an affordable medication, whereas others post tragic videos highlighting their inability to get the medication they so desperately need. While there are many potential insulin products, the variability in patient experience is itself demonstrative of how an insulin product, with a manufacturer list price, and a price paid by the dispensing pharmacy to acquire it, can yield such divergent perspectives on insulin prices.

Whether directly related to these patient stories or not, legislation was passed, signed into law, and enacted which capped the amount of money Medicare beneficiaries can be required to pay to get a month’s supply of insulin. The Inflation Reduction Act (Biden) capped the monthly price of insulin at $35 for Medicare enrollees starting in 2023. Which means regardless of the historic harms with insulin we have showed with rebates (Money from Sick People Part I) or a provider’s deeply discounted acquisition cost (Money from Sick People Part II), Medicare enrollees can expect some form of price protection from these past behaviors. Undoubtedly a good thing.

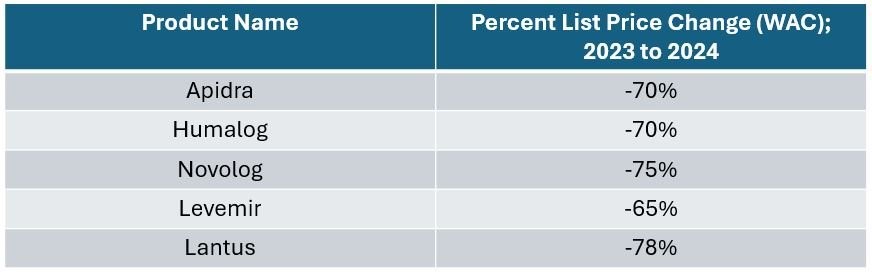

However, the value of those savings are perhaps less than when originally envisioned. Why? Well, insulin products (not all, but the majority from a utilization standpoint) took price decreases (like massive, 70%+ decreases) in 2024. For those who may have missed it (undoubtedly not a regular 46brooklyn reader), five insulin products took significant drug list price decreases at the start of January 2024 (technically some squeaked in the last week of 2023, but we’re calling those 2024 price decreases). Specifically, as shown in our Brand Drug List Price Box Score.

Figure 1 below outlines the product and the extent of their price decreases:

Figure 1 Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, 46brooklyn Research

The significance of these price drops was not lost on us, given the history of controversy surrounding the insulin marketplace dynamics. And while there some good coverage of these big cuts, we understand why more casual observers may have missed them, since the years of headlines of rising insulin prices far outmatched the coverage of their cratering.

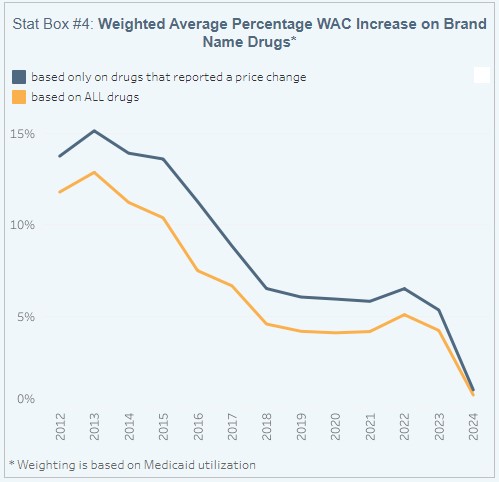

These drugs, which were priced at several hundreds of dollars per package previously, are all now below $100 a package (at least, on the basis of the manufacturer set-list price). The impact of these price decreases are such that they more or less broke our perception of manufacturer list price behavior changes broadly (at least as measured within our Brand Box Score in Figure 2 to the right (Source: Elsevier Gold Standard Drug Database, CMS State Drug Utilization Data, 46brooklyn Research). This is because these products represent a lot of historical proportional drug spending, and so when we attempt to weight price change experience across brand drugs, we perceive almost no list price change behavior for 2024; a first-time observation in more than a decade of drug pricing context (see previous discussion of the phenomenon and the Brand Drug Pricing Box Score).

To demonstrate just how important these products are to our broader prescription drug ecosystem, the five insulin products outlined above had (Figure 1) over $11 billion in gross drug spending across almost 14 million prescriptions in 2022 in Medicare (the last year that has public data available regarding Medicare spending and utilization). These products are significant enough to represent roughly 1% of drug utilization in Medicare and 5% of gross drug spending. Said differently, one in 20 dollars spent at the pharmacy counter in Medicare was an insulin dollar.

Unsurprisingly, the list price reductions received a lot of positive praise from a variety of sources. And yet, we still cannot reasonably explain insulin prices at the pharmacy counter in relation to the manufacturer list price or the pharmacy’s cost to acquire.

What do we mean?

Well, consider what we might perceive to be the importance of these price decreases relative to the value offered from the $35 insulin copay cap. To do this, we will look at the full wholesale acquisition cost (WAC) price for the most commonly utilized Medicare insulin – Lantus (we’re going to specifically look at the 10 mL vial; this is one we’ve previously used in our Money From Sick People series, so it helps keep things consistent).

In 2023, before Lantus’ price decrease, one vial of Lantus ran $292, which means that the Medicare $35 copay max would have meant a patient was paying roughly 10% of the manufacturer’s list price. In 2024, after Lantus’ price decrease, one vial of Lantus now costs $64, meaning that the $35 cap means the patient is paying around 54% of the manufacturer’s list price.

What we can start to see is that while it can be beneficial to some for manufacturers to lower their price, the end result of list price decreases is not one that is guaranteed to be universally of benefit. We all (including Medicare beneficiaries) have to pay money (via premiums) to get access to the benefit of cost sharing for medicines at the pharmacy counter (i.e., the $35 cap vs. the full manufacturer list price), and how much value our premium dollars secure (i.e., how much protection we get from gross prices at the pharmacy counter) is a function of how much value the health plan passes on to the end-user. This was the point we made back with Money from Sick People Part I in regards to rebates, but may need revisited in light of lower priced insulins. If that sounds intriguing, then read on to our analysis of “Money from Sick People” Part IV, where we attempt to explain how messed up insulin drug prices remain using the largest insurer in the country: Medicare.

Mission accomplished: Manufacturers lower insulin prices

Undoubtedly, there are some who have more or less exclusively advocated for the idea that if drug manufacturers would just lower their drug prices, we would all benefit. Certainly, we can understand how if one believes that drug manufacturers are alone responsible for the end drug pricing experience, then advancing and advocating for policies that would cap manufacturer prices would seem to make sense (if we accept the premise that price controls would have no other collateral harms). If the matter is as simple as manufacturers setting lower list prices, then success would be measured relatively simply for the insulin products outlined above.

Said differently, we know the degree to which manufacturer list prices for insulins changed – with price cuts that range from 65% to 78% – and so we would expect that if the degree of those list price changes correlated with the changes in insulin prices experienced in Medicare, then we would undoubtedly be able to claim drug pricing success. The set up was such that we could not resist taking a look.

So, rather than listen to the words of advocacy groups, let’s ask the question to Medicare’s own drug pricing data:

Are drug companies alone responsible for the prices we pay for medicines?

To begin, we need to discuss our data source for this analysis. The Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) publishes in the public domain a set of files referred to as the “Quarterly Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information.” As described by CMS, these files provide information on Part D formulary, pharmacy network, and pricing data for Medicare Prescription Drug Plans and Medicare Advantage Plans. Specific to drug prices, which is what we’re interested in (this is 46brooklyn, duh), CMS states the pricing information provided reflects “plan level average monthly costs for formulary Part D drugs.” Digging deeper (see FAQ), the pricing information is actually broken out in a couple ways, such as being potentially variable whether the day supply is 30 or 90 days for the plan, but should reflect, “the average cost for the day supply at in-area retail pharmacies for the Medicare plan.”

In a way, and as a quick sidebar, these acknowledgements by CMS are welcomed by those of us at 46brooklyn, as they represent, from a certain point-of-view, that drug pricing is not subject to just the manufacturer list price. Why would we need to acknowledge that a 30-day unit price may not equal a 90-day unit price if manufacturers alone were responsible for drug prices. In case it isn’t obvious, manufacturers have no bearing on the day supply of the prescription dispensed, rather that is a function of patient need, prescriber decision making, pharmacist approval, and plan benefit decisions to allow or disallow the practice of extended days supplies. And yet, we accept and acknowledge that prices are variable based upon days supply such that we also acknowledge the forces beyond manufacturer list price.

With the assurance gathered from the background on the CMS data source, we pressed ahead with gathering these files for 2023 and 2024 such that we could compare the Medicare insulin pricing experience pre- and post-drug manufacturer list price decreases at the Medicare plan level. As the files are published quarterly, and not all of 2024 has elapsed, we elected to grab the Q1 files for both 2023 and 2024 to have as ‘apples-to-apples’ comparison as we could set up at the start. In this way, we can directly observe who did and who did not benefit from drug list price decreases and hopefully see if list price changes resulted in a shared universal experience for all (spoiler alert: they did not).

As way of quick reminder, we have already acknowledged that as of January 1, 2023, there has been a cap for a month’s supply for each insulin product in Medicare. Specifically, no prescription drug plan in Medicare can charge more than $35 per month’s supply of each insulin product (regardless of whether the insulin is a preferred or non-preferred product). We make this note of distinction because the Medicare plan cost does not necessarily equal the Medicare enrollee’s cost (at least not directly).

As we already demonstrated, the perception of value of the $35 patient out-of-pocket cap changed based upon these list price changes, but we’re principally gathering the pricing data from Medicare to analyze the plan’s drug pricing view (as patients are already shielded from past Money from Sick People policy). Again, and for emphasis, CMS states the pricing information we’re relying upon reflects “plan level average monthly costs for formulary Part D drugs.” Nevertheless, if manufacturer list price = drug price (and nothing else matters in that equation), then we expect a list price decrease to perfectly equal a plan drug price decrease.

A few more housekeeping items before we get into the analysis . . . We pay premiums for insurance, including in Medicare, in part to access coverage and get financial protection against potentially costly claims. If there are more claims or higher cost claims, the cost of insurance premiums will go up (regardless of whether we’re talking drug costs or homes or cars). For prescription drug insurance, the prices we’re reviewing are the gross drug prices of the plan (which our analysis will focus on), and we should acknowledge that regardless of our findings on plan costs, patients needing insulin were more or less protected at the pharmacy counter from the pricing disparities we are going to investigate (though that may or may not have benefited them in the end). Furthermore, we should also recognize that for 2024, changes in the handling of Medicare direct and indirect remuneration (DIR) require that pharmacy prices reflect the “lowest possible reimbursement” for a Part D drug. We interpret this to mean that while the 2023 prices we will review may be inflated by a degree of unknown pharmacy DIR, no amount of pharmacy DIR would be anticipated to reasonably explain any observed differences in the 2024 files (given the rule). This is important, as it represents a potential difference in perception to interpreting the 2023 price variability that cannot be readily used to explain any potential 2024 price variability.

There is always more to say, but we think that is sufficient enough background to begin. As always, we encourage our readers to read the information of the underlying data source (i.e., the Quarterly Prescription Drug Plan Formulary, Pharmacy Network, and Pricing Information) before we begin to offer our perspective on what these drug prices mean.

Next Up an Analysis of Pricing and its Variability for Insulin.