Running on Empty tonight. VA sent me a letter asking for all the information I believe was already sent to them. Some I have found rather quickly by exploring U of M records. Platelet counts for certain periods when they just almost disappeared. I need to talk to them tomorrow and see what the issue is or was. I have been in some of the little towns near Switzerland Rietheim-Weilheim, Germany comes to mind. Nice read . . . enjoy. Villages Without Cars by Taras Grescoe Straphanger Blog In the Swiss Alps, I Explore an Automobile-Free Paradise When you think about it, there are very few inhabited places in the world that haven’t been touched by automobile traffic. The empire of internal combustion and asphalt has stretched its

Topics:

Bill Haskell considers the following as important: Town without cars, US/Global Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes How Tesla makes money

Angry Bear writes True pricing: effects on competition

Angry Bear writes The paradox of economic competition

Angry Bear writes USMAC Exempts Certain Items Coming out of Mexico and Canada

Running on Empty tonight. VA sent me a letter asking for all the information I believe was already sent to them. Some I have found rather quickly by exploring U of M records. Platelet counts for certain periods when they just almost disappeared. I need to talk to them tomorrow and see what the issue is or was.

I have been in some of the little towns near Switzerland Rietheim-Weilheim, Germany comes to mind. Nice read . . . enjoy.

Villages Without Cars

by Taras Grescoe

Straphanger Blog

In the Swiss Alps, I Explore an Automobile-Free Paradise

When you think about it, there are very few inhabited places in the world that haven’t been touched by automobile traffic. The empire of internal combustion and asphalt has stretched its tendrils into virtually every hamlet and outpost, no matter how small, on the globe. The few exceptions are those places whose unique geography militates against driving. Islands, for example, like Mackinac Island in Lake Huron, which has no bridge connection to Michigan, and where horse-drawn carriages are still the norm. The center of Dubrovnik, whose narrow streets are huddled within medieval walls. And, most famously, Venice, where the streets are canals and the city buses are vaporetti.

I once spent a week in Switzerland’s most famous car-free village, Zermatt, which serves as a gateway to the best-known of the Alps, the shark-fin-shaped Matterhorn. I was researching a chapter of a book that became The End of Elsewhere, about the impact of mass tourism on cultures and the environment. Zermatt, elevation 1,620 metres, was an excellent case study, because it has been a destination for tourists, starting with English and German mountaineers, since the 19th century. As expected, I found it to be highly commercialized, with touristy fondue restaurants, McDonald’s and other fast-food joints, high-end shops and over one hundred hotels (most of them well beyond my limited means—I ended up renting a space in an attic, reached by a ladder, and where I inevitably conked my head on a rafter when I woke up too abruptly).

Before arriving, I hadn’t registered the fact that there was no road into Zermatt. I came from Brig aboard the Glacier Express, a rack railway that dropped me off in the village’s main drag, the Bahnoffstrasse; but drivers had to leave their cars at a vast parking lot in the village of Täsch, elevation 1,449 metres, and take a shuttle bus or narrow-gauge cog railway to Zermatt.

While I gritted my teeth at the fakery of the village—for decades, the tourist office has paid to have a troupe of long-haired goats driver through the streets at 4:30 pm every day, for the tourists to photograph—I also came to enjoy the sensation of strolling its precipitous streets without having to constantly look over my shoulder to make way for an approaching Opel or BMW.

But I filed away “The Swiss Car-Free Village” into the category of Tourist Phenomena, along with the Mackinacs and Venices of the world—interesting, but not really real, if you know what I mean. Last week, though, I was in Switzerland, and I got to spend a night in a village that was genuinely car-free, but also a genuine place.

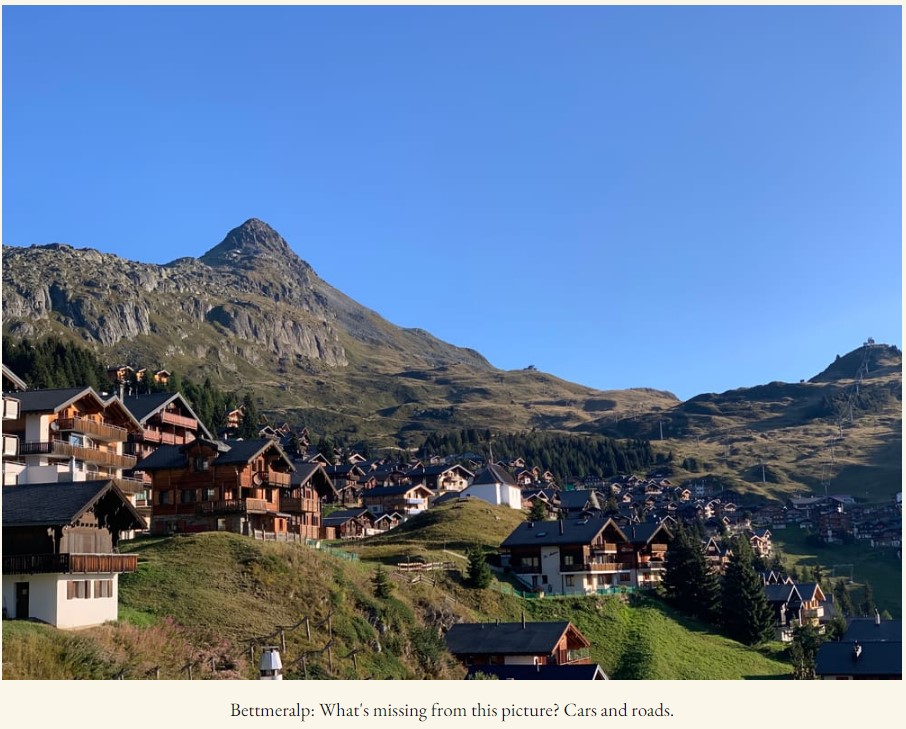

I’m talking about the village of Bettmeralp, which is the gateway to the Bettmerhorn (2,872 metres) and the Aletsch Glacier, the largest in the Alps. I arrived from Brig, on the Matterhorn-Gotthard Bahn, a cog railway whose clerestory windows offer panoramic views of the passing peaks, and got off at the Betten Talstation, a gondola station. Now, this is probably sounding to you like a classic winter resort, and the Aletsch Arena, as the area is known, is a destination for snowboarders and skiers.

But the gondolas also serve as a form of year-round transportation for local residents. Two operate from the station, in fact: a large, express gondola direct to Bettmeralp (more on that later) and a smaller gondola, which stops at the (car-accessible) village of Betten Dorf, where you transfer to another small gondola to Bettmeralp. I rode the latter, local service, squeezing on next to a bearded hunter in camo gear, who was taking his dog and rifle to hunt for deer and boar.

Emerging onto the main street of Bettmeralp, I had a flashback to being in Zermatt, twenty years earlier: without planning it, I’d somehow got myself to a car-free paradise. The gondola station was clearly the “downtown” of this village of fewer than 500 inhabitants; our arrival provoked a wave of foot traffic, which quickly dissipated as people disappeared into lanes and down outdoor stairways. Outside the station, two grade-school boys were hosing the mud off their mountain bikes at a “Bike Washing Machine” (bringing a dirty bike onto the gondola earns you very dirty looks, apparently). They began to giggle as a yellow Swiss Post truck approached, and sprayed the windshield. In mock rage, the driver accelerated towards the boys, and they giggled madly as they squirted him in the face. A jocular joust, obviously.

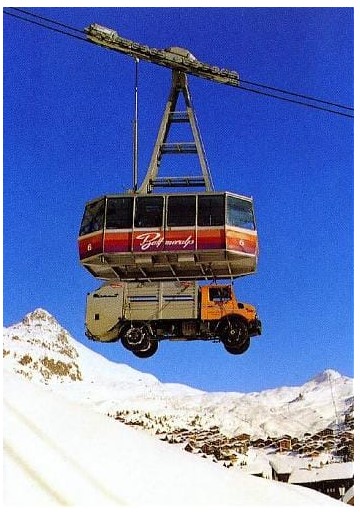

Now, when I say truck, I should be clear: this was a teeny-tiny electric vehicle, which ran silently through the streets as the mailman made his rounds. Every other vehicle I saw was of a similar size. Every hotel had an electric cart-truck for collecting luggage (and guests with mobility limitations) from the station. Some drivers had attached small cowbells to warn pedestrians they were coming. The largest vehicle you’ll ever see in the streets of Bettmeralp is a diesel-powered garbage truck. Amazingly, they dangle it from the underside of the other gondola (the large, express cable-car), and then bring it back down to the valley when it’s finished its work.

Bettmeralp isn’t a tourist simulacrum of a village. Zermatt’s main street is full of Rolex shops and international chains; Bettmeralp does have a few bike and ski rental shops, but residents’ houses outnumber hotels and guesthouses. One of the main businesses is a Coop supermarket. I talked to a guide who lives in the valley who says he sometimes rides the gondola here to do his shopping, because it’s the only grocery store in the area that’s open on Sundays. On the afternoon of my arrival, I rode yet another cable car to beneath the peak of Bettmerhorn, and walked to the platform that overlooks the Aletsch Glacier, which feeds the Rhône River. (A poignant sight: it is currently 20 kilometers long, and 800 metres thick at one point, but it is melting quickly, and is expected to disappear completely by the end of the century.)

The following morning, I took a stroll around the village, and stumbled on something I’ve never encountered before in my travels: a self-service funicular. You just walk in, press a button, and you’re whisked through the treetops down an incline railway. My kind of morning commute!

Another sign this is a real community: there’s a public bus service. I rode it to the village of Riederalp, which is also car-free. This is real transit, not a tourist shuttle: the small electric buses leave at regular times (often on a half-hour schedule), and make regular stops along the way. What’s more, they arrive at the Riederalp cable car station, where they are timed to leave when the gondola arrives and departs. The residents I talked to said that almost everybody walks or rides bikes (I saw a lot of e-bikes, because the streets are steep), but that they found the buses useful when they were running late and were taken by visitors and elderly people.

In the past, I’ve thought of gondolas and cable-cars as a form of tourist transfer, but lately I’m coming around to the idea that they can be full-fledged forms of public transport. That’s the case with the Roosevelt Island cable car in New York City, and Medellín in Colombia is famous for its gondola transit network. And in the car-free villages of Bettmeralp and Riederalp, I saw far more local residents—school kids, workers—than visitors using the gondolas to get around. In fact, I realized they served as a form of multi-modal transit as I took the gondola back to the valley from Riederalp. The “local” gondola stopped at a station mid-point, where bicycle riders hustled across the suspended platform to board another gondola. This was a mini-network, and it was being used for commuting.

This might seem incredible to readers from North America; it did to me. There are about ten car-free villages in Switzerland (you can find a guide to them here). I’ve already made a case in this dispatch that Switzerland may have the world’s best transit; and, in weeks to come, I’ll write more about the way that this very sensible nation makes car-free living possible, even in the most unexpected places.

The best thing about Bettmeralp? The tranquility. I could hear the bells of the cows grazing on the slopes, the barking of dogs, the laughter of children, the rushing of waterfalls. Funny: it’s not until you erase cars, whose honking, and alarming, and wheel-rushing have become the default soundtrack to our lives, that you realize how much they’ve robbed from our sensual experience of the world.