Modeling the numbers on bottom-up and middle-out economics. How Redistribution Makes Us All Richer, Wealth Economics, Steve Roth You hear a lot about bottom-up and middle-out economics these days, as antidotes to a half-century of “trickle-down” theorizing and rhetoric. You’re even hearing it, prominently, from Joe Biden. [embedded content] They’re compelling ideas: put more wealth and income in the hands of millions, or hundreds of millions, and you’ll see more economic activity, more prosperity, and more widespread prosperity. To its proponents, it seems downright intuitive or even obvious, a formula for The American Dream. But curiously, you don’t find much nuts and bolts economic theory supporting that view of how economies work.

Topics:

Steve Roth considers the following as important: Hot Topics, US EConomics

This could be interesting, too:

NewDealdemocrat writes JOLTS revisions from Yesterday’s Report

Joel Eissenberg writes No Invading Allies Act

Bill Haskell writes The North American Automobile Industry Waits for Trump and the Gov. to Act

Bill Haskell writes Families Struggle Paying for Child Care While Working

Modeling the numbers on bottom-up and middle-out economics.

How Redistribution Makes Us All Richer, Wealth Economics, Steve Roth

You hear a lot about bottom-up and middle-out economics these days, as antidotes to a half-century of “trickle-down” theorizing and rhetoric. You’re even hearing it, prominently, from Joe Biden.

They’re compelling ideas: put more wealth and income in the hands of millions, or hundreds of millions, and you’ll see more economic activity, more prosperity, and more widespread prosperity. To its proponents, it seems downright intuitive or even obvious, a formula for The American Dream.

But curiously, you don’t find much nuts and bolts economic theory supporting that view of how economies work. There’s been lots of research on the sources and causes of wealth and income concentration. There’s been a lot of important work on the social and political effects of inequality. But unlike the steady stream of “incentive” theory from Right economists over decades, economists have mostly failed to ask or answer a rather basic theoretical (and empirical) question: what are the purely economic effects of highly-concentrated wealth, held by fewer people, families, and dynasties, in larger and larger fortunes?

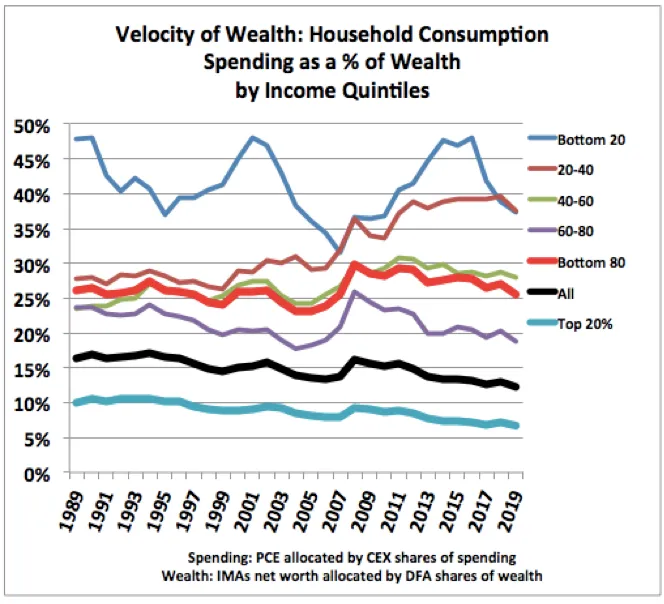

In a paper and model published in Real-World Economics Review, I try to tackle that question. The model takes advantage of national accountants’ household wealth measures that have only been available since 2006, and measures of wealth distribution that were only first published in 2019. Combined with thirty+ years of consistent survey data on consumer spending at different income levels, the paper derives a novel economic measure: velocity of wealth.1

The top 20% only turns over ~7% of its wealth each year in spending. The rest, it just sits on like Smaug the Dragon (with individuals wealthholders adjusting their portfolio mixes here and there). The bottom 80% turns its wealth over in spending three or four times as fast (25% a year). The arithmetic takeaway: at a given level of wealth, more broadly distributed wealth means more spending, the very stuff of economic activity, which is itself the ultimate source of wealth accumulation.

The details of the model are somewhat more complex, but it only employs five easy to understand formulas — all basically just arithmetic, and all expressed without resort to abstruse symbols; they use plain language. The model only depicts one economic effect, the wealth-velocity/spending effect (there are innumerable others), but it’s an effect that’s absent in traditional and even much heterodox/post-Keynesian empirical modeling. (Keynes’ consumption function doesn’t even have a wealth term.)

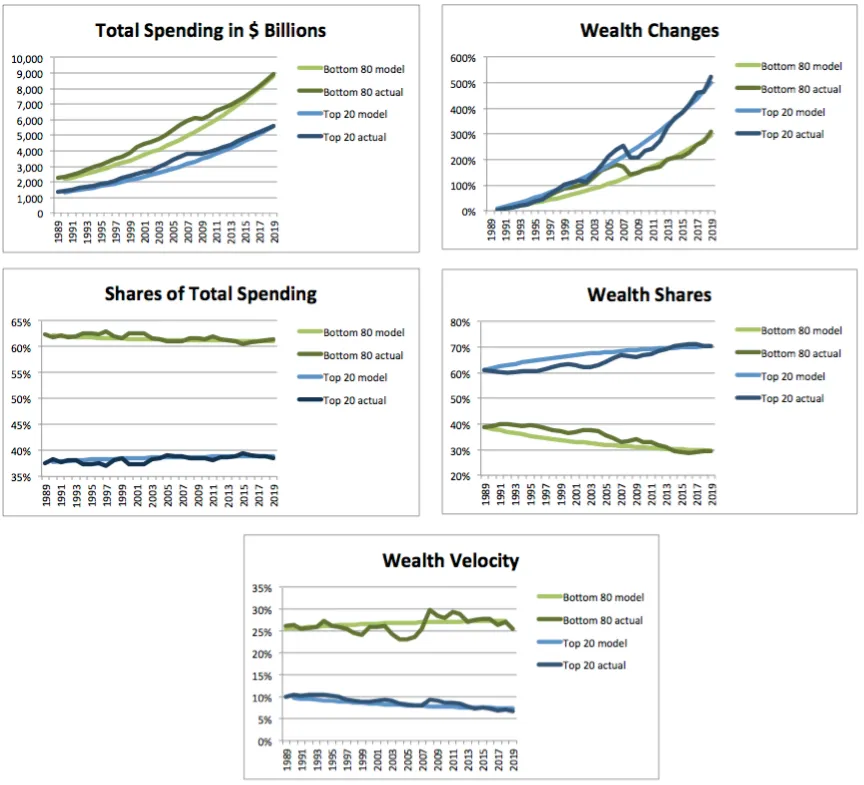

How good are the model’s predictions? It starts with just two numbers in 1989 — the wealth of the top 20% and the bottom 80% — and extrapolates forward using those few formulas to predict levels of wealth, spending, and shares of wealth and spending, thirty years later.

Compare the model’s predictions for 2019 to actual results; in each case they’re almost identical.

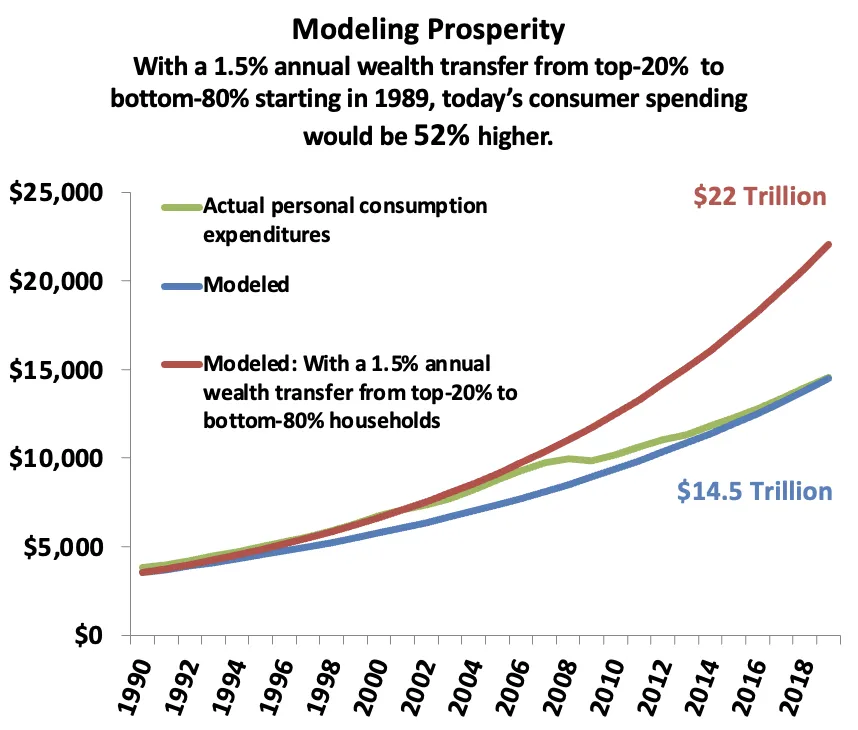

It’s easy to add counterfactuals to this model: what would have happened if some percentage of top-20% wealth was transferred, redistributed, to the bottom 80% every year over those three decades? The results are pretty eye-popping.2

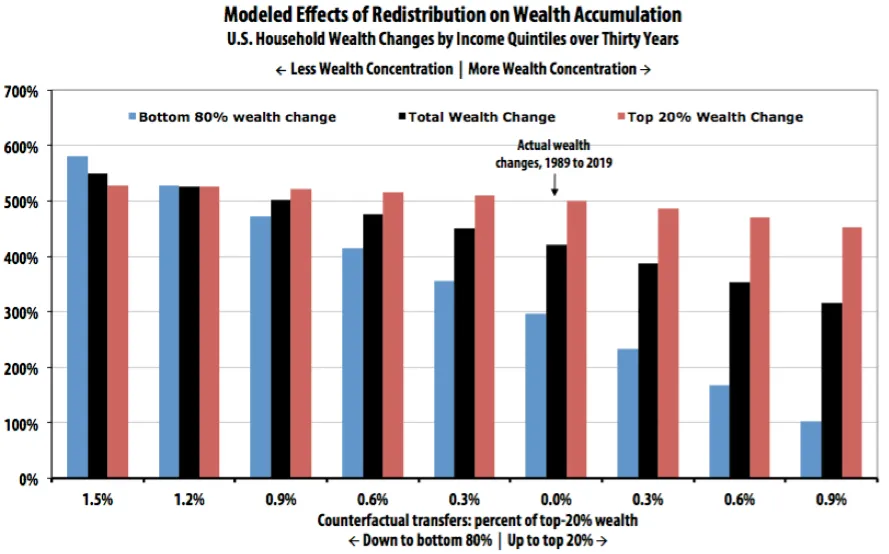

Downward redistribution results in more spending, more economic activity, and makes everyone quite a lot wealthier, faster — especially (no surprise) the bottom 80%. Taking the leftmost bars as an example: with an annual 1.5% downward transfer, greater spending would have resulted in a 549% total wealth increase, versus actual 421%.3

Most of that extra wealth growth would have gone to the bottom 80% (wealth growth of 527% vs actual 295%), while top-20% wealth growth would also have been slightly higher than actual (526% vs 499%). The top-20% share of wealth would have remained unchanged, versus the rather extreme top-20 wealth-share increase that actually happened: up from 61% to 71%.

Bottom line: With 1.5% in annual downward redistribution starting in 1989, 2019’s total wealth would be 16% higher. Spending would be 52% higher.

It’s worth noting: excepting the two leftmost scenarios (1.5% and 1.2%), the top 20% keep getting relatively richer than the bottom 80%. Avoiding the increased wealth concentration that we’ve seen since 1989 (or even reducing the 1989 concentration, perish the thought) would have required at least an annual 1.2–1.5% downward wealth transfer from the top 20%.

The extreme rich, of course, might not have gotten richer with this downward redistribution. It would depend on the mechanics and progressivity of the taxes and transfers. The data available here don’t let us determine that using this model. But the transfers would have to be far larger than envisioned here before top-percentile wealth levels (vs their relative share) actually stagnate or decline.

Absent quite extreme redistribution, the wealthy keep getting wealthier as the economy grows. But with adequate redistribution to counter the ever-present trend toward economy-crippling wealth concentration, everybody else prospers as well.

1 “Velocity of money” is of course a familiar monetarist construct. But in monetarist practice it focuses only on “money”/cash assets (mainly checking deposit holdings), which only comprise about 10% of household assets. So it (silently) rests on a false behavioral assumption: that people buy fancy cars because they have a high proportion of cash assets in their portfolios, as opposed to just having…lots of assets. Which of those rings true?

2 Again, this is only modeling a single economic effect. Many others could or would certainly have emerged or resulted from this one. But the quite huge magnitude and sheer arithmetic inevitability of this effect is large enough to suggest it would still have pertained to a decent extent, notwithstanding any others.

3 To put that 1.5% downward transfer in context: the total return on a passive wealthholder’s 60/40 stock/bond portfolio over those thirty years was about 7.5%. That’s all-unearned income, received simply for holding wealth. With the transfer, wealth holders would only have received 6% annual unearned income returns. The horror.