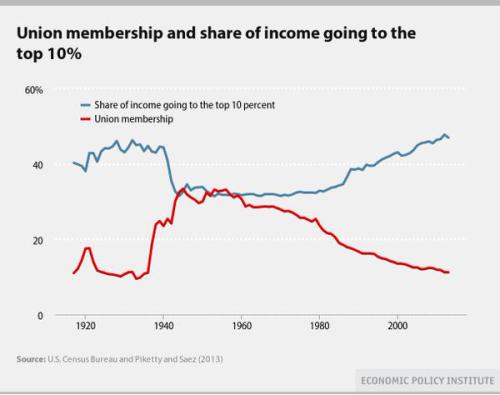

This chart is pretty wow: Florence Jaumotte and Carolina Osorio Buitron of the International Monetary Fund have some ideas about how the correlation may have been caused: The main channels through which labor market institutions affect income inequality are the following: Wage dispersion: Unionization and minimum wages are usually thought to reduce inequality by helping equalize the distribution of wages, and economic research confirms this. Unemployment: Some economists argue that while stronger unions and a higher minimum wage reduce wage inequality, they may also increase unemployment by maintaining wages above “market-clearing” levels, leading to higher gross income inequality. But the empirical support for this hypothesis is not very strong, at least within the range of institutional arrangements observed in advanced economies (see Betcherman, 2012; Baker and others, 2004; Freeman, 2000; Howell and others, 2007; OECD, 2006). For instance, in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development review of 17 studies, only 3 found a robust association between union density (or bargaining coverage) and higher overall unemployment. Redistribution: Strong unions can induce policymakers to engage in more redistribution by mobilizing workers to vote for parties that promise to redistribute income or by leading all political parties to do so.

Topics:

John Aziz considers the following as important: 2011, 2015, 2020, aggregate demand, banksters, Economic History, Economics, financialization, industrial policy, inequality, reagan, thatcher

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

This chart is pretty wow:

Florence Jaumotte and Carolina Osorio Buitron of the International Monetary Fund have some ideas about how the correlation may have been caused:

The main channels through which labor market institutions affect income inequality are the following:

Wage dispersion: Unionization and minimum wages are usually thought to reduce inequality by helping equalize the distribution of wages, and economic research confirms this.

Unemployment: Some economists argue that while stronger unions and a higher minimum wage reduce wage inequality, they may also increase unemployment by maintaining wages above “market-clearing” levels, leading to higher gross income inequality. But the empirical support for this hypothesis is not very strong, at least within the range of institutional arrangements observed in advanced economies (see Betcherman, 2012; Baker and others, 2004; Freeman, 2000; Howell and others, 2007; OECD, 2006). For instance, in an Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development review of 17 studies, only 3 found a robust association between union density (or bargaining coverage) and higher overall unemployment.

Redistribution: Strong unions can induce policymakers to engage in more redistribution by mobilizing workers to vote for parties that promise to redistribute income or by leading all political parties to do so. Historically, unions have played an important role in the introduction of fundamental social and labor rights. Conversely, the weakening of unions can lead to less redistribution and higher net income inequality (that is, inequality of income after taxes and transfers).

I have spent a lot of time thinking about what has caused the major upswing in inequality since the 1980s.

Back in 2011 and 2012 my analysis tended to emphasize financialization and specifically the massive growth in credit creation that took place since the 1980s. I think this was a rather naive view to take.

I don’t think I was wrong to look at financialization. Obviously, unchecked credit creation is a plausible pathway for the rich to make themselves and their friends richer. I just think it was naive to not see financialization — like deunionization, like globalization, and like trends in housing wealth — as part of a broader pie.

My hypothesis is that what changed is that politicians decided that greed was good and that “industrial policy” was a dirty phrase. The political structures that emerged in the wake of the Great Depression and World War 2 which together greatly limited inequality — welfare states, nationalized industries, unionized workforces, constrictive financial regulations like Glass Steagall — were severely rolled back. This created an opening for the rich to get much richer very fast, which they did.

If I’m right, it would take a major political shift in the other direction to start reducing inequality.