Someone emailed me this Tweet about MMT asking whether I thought it was accurate or not: Okay. Disclaimer – I like a lot of what MMT says. But they take this funding narrative too far and I think it discredits their other more important narratives. This Tweet gets to a pretty fundamental problem in the MMT narrative. MMT people like to say that taxes don’t fund government spending and that the government doesn’t need income to spend. This is wrong in a rather basic sense. After all, in theory no one needs income to spend because we can spend on credit. As long as you have a willing creditor you have spending power. At the aggregate private sector level all the things MMT says about governments are true – they don’t pay back their debts, they expand their balance sheets endogenously,

Topics:

Cullen Roche considers the following as important: Most Recent Stories

This could be interesting, too:

Cullen Roche writes Understanding the Modern Monetary System – Updated!

Cullen Roche writes We’re Moving!

Cullen Roche writes Has Housing Bottomed?

Cullen Roche writes The Economics of a United States Divorce

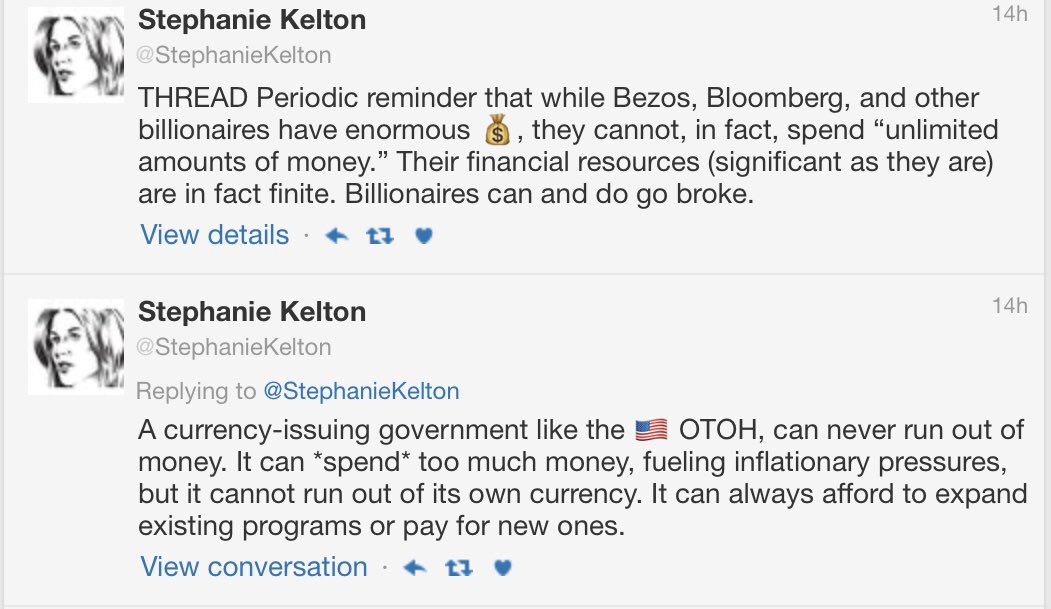

Someone emailed me this Tweet about MMT asking whether I thought it was accurate or not:

Okay. Disclaimer – I like a lot of what MMT says. But they take this funding narrative too far and I think it discredits their other more important narratives.

This Tweet gets to a pretty fundamental problem in the MMT narrative. MMT people like to say that taxes don’t fund government spending and that the government doesn’t need income to spend. This is wrong in a rather basic sense. After all, in theory no one needs income to spend because we can spend on credit. As long as you have a willing creditor you have spending power. At the aggregate private sector level all the things MMT says about governments are true – they don’t pay back their debts, they expand their balance sheets endogenously, they can create money, they can monopolize certain forms of money, if they save too much it can create problems, etc.

Understanding that, it’s important to note that taxes (and income of any type) reflect past production and movement of resources. The more output that a government can tax the more spending power they have because they have more resources supporting that spending. This is very basic endogenous money theory. As you might know from your credit card, your spending isn’t constrained dollar for dollar by your income, but your credit is necessarily constrained by your output/income. This can be a confusing point, but it’s an important one and it’s a rather big hole in MMT’s narrative.

The rich people Stephanie Kelton refers to are interesting in the context of all of this because they pose a big problem for MMT. After all, MMT says you don’t need to tax to spend. And so if you don’t need to tax to spend then why do we need to tax rich people at all? MMT will say that we need to do it for other reasons (like reducing inequality). Fine, but let’s think about a world with fewer rich people or even no rich people. After all, a world with fewer rich people is just a world with fewer resources. Wealthy countries aren’t just crony capitalism run amok (although there might be an element of that). They are countries where people have produced things that the underlying markets and consumers value thereby rewarding certain people (usually the founders of companies) with wealth. Yes, that wealth might be unequally distributed at times and that poses a different problem, but a country being wealthy in the aggregate is a very good problem to have.

This all poses its own big problem for MMT. After all, without rich people and the resources they’ve produced the whole MMT narrative starts to fall apart because even in the MMT narrative you need underlying resources and a country with lots of rich people reflects a country with a lot of resources. And that wealth helps afford us with the ability to have a larger government because we have more resources that support those needs. This is good. And we should strive for this. But what we shouldn’t do is take this narrative to an extreme and start saying that we can “always afford to expand existing programs” or that we don’t need taxes to fund spending because this takes us into a slippery slope of an inflation theory where the implication is that government spending creates its own demand for money. This is like some sort of warped version of Says Law where countries with high inflations just need to spend more to reduce the inflation. W. T. F.¹

The bottom line is that everyone funds their balance sheet expansion by having productive underlying resources and having a printing press (or Warren Buffett’s line of credit) doesn’t make you immune to counterparty risk. I’m cool with trying to reduce income inequality. And we shouldn’t let the extremists on the other end of the spectrum scare us into thinking that the US government is bankrupt or running out of money. But we also shouldn’t take it too far and start claiming that government spending is self funding. That’s a bridge too far and assumes a theory of inflation that has virtually zero evidence to support itself.

NB – Anyone familiar with MMT knows that you can’t debunk it. After all, no country has ever even tried MMT, which, at its core, is really just an okay-ish description of the monetary system leading to the prescription of an employment buffer stock (what they call the Job Guarantee). Since the Job Guarantee has never been tried in scale in any country it’s virtually impossible to say whether this theory is right or not.

¹ – This is arguably the more interesting element of this discussion and also the much nerdier one. After all, MMT people don’t seem to have a coherent theory of inflation aside from constantly repeating the trope that government spending is constrained by resources. Well, yes, but if we don’t need to tax other output then the obvious implication is that new money creation can be supported by the resources it creates. This assumes that the government’s spending is productive and creates the very demand that makes its balance sheet sustainable in the long-run. Is this a well supported theory of inflation? Methinks not.