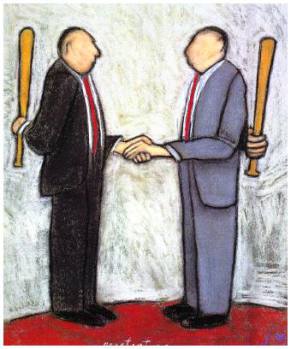

Walked-out Harvard economist Greg Mankiw has more than once tried to defend the 1 % by invoking Adam Smith’s invisible hand: [B]y delivering extraordinary performances in hit films, top stars may do more than entertain millions of moviegoers and make themselves rich in the process. They may also contribute many millions in federal taxes, and other millions in state taxes. And those millions help fund schools, police departments and national defense for the rest of us … [T]he richest 1 percent aren’t motivated by an altruistic desire to advance the public good. But, in most cases, that is precisely their effect. When reading Mankiw’s articles on the “just desert” of the 1 % one gets a strong feeling that Mankiw is really trying to argue that a market economy is some kind of moral free zone where, if left undisturbed, people get what they “deserve.” Where does this view come from? Most neoclassical economists actually have a more or less Panglossian view on unfettered markets, but maybe Mankiw has also read neoliberal philosophers like Robert Nozick or David Gauthier. The latter writes in his Morals by Agreement: The rich man may feast on caviar and champagne, while the poor woman starves at his gate. And she may not even take the crumbs from his table, if that would deprive him of his pleasure in feeding them to his birds.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Walked-out Harvard economist Greg Mankiw has more than once tried to defend the 1 % by invoking Adam Smith’s invisible hand:

[B]y delivering extraordinary performances in hit films, top stars may do more than entertain millions of moviegoers and make themselves rich in the process. They may also contribute many millions in federal taxes, and other millions in state taxes. And those millions help fund schools, police departments and national defense for the rest of us …

[T]he richest 1 percent aren’t motivated by an altruistic desire to advance the public good. But, in most cases, that is precisely their effect.

When reading Mankiw’s articles on the “just desert” of the 1 % one gets a strong feeling that Mankiw is really trying to argue that a market economy is some kind of moral free zone where, if left undisturbed, people get what they “deserve.”

When reading Mankiw’s articles on the “just desert” of the 1 % one gets a strong feeling that Mankiw is really trying to argue that a market economy is some kind of moral free zone where, if left undisturbed, people get what they “deserve.”

Where does this view come from? Most neoclassical economists actually have a more or less Panglossian view on unfettered markets, but maybe Mankiw has also read neoliberal philosophers like Robert Nozick or David Gauthier. The latter writes in his Morals by Agreement:

The rich man may feast on caviar and champagne, while the poor woman starves at his gate. And she may not even take the crumbs from his table, if that would deprive him of his pleasure in feeding them to his birds.

Now, compare that unashamed neoliberal apologetics with what three truly great economists and liberals — John Maynard Keynes, Amartya Sen and Robert Solow — have to say on the issue:

The outstanding faults of the economic society in which we live are its failure to provide for full employment and its arbitrary and inequitable distribution of wealth and incomes … I believe that there is social and psychological justification for significant inequalities of income and wealth, but not for such large disparities as exist to-day.

John Maynard Keynes General Theory (1936)

The personal production view is difficult to sustain in cases of interdependent production … i.e., in almost all the usual cases … A common method of attribution is according to “marginal product” … This method of accounting is internally consistent only under some special assumptions, and the actual earning rates of resource owners will equal the corresponding marginal products”only under some further special assumptions. But even when all these assumptions have been made … marginal product accounting, when consistent, is useful for deciding how to use additional resources … but it does not “show” which resource has “produced” how much … The alleged fact is, thus, a fiction, and while it might appear to be a convenient fiction, it is more convenient for some than for others….

The personal production view … confounds the marginal impact with total contribution, glosses over the issues of relative prices, and equates “being more productive” with “owning more productive resources” … An Indian barber or circus performer may not be producing any less than a British barber or circus performer — just the opposite if I am any judge — but will certainly earn a great deal less …

Amartya Sen Just Deserts (1982)

Who could be against allowing people their ‘just deserts?’ But there is that matter of what is ‘just.’ Most serious ethical thinkers distinguish between deservingness and happenstance. Deservingness has to be rigorously earned. You do not ‘deserve’ that part of your income that comes from your parents’ wealth or connections or, for that matter, their DNA. You may be born just plain gorgeous or smart or tall, and those characteristics add to the market value of your marginal product, but not to your deserts. It may be impractical to separate effort from happenstance numerically, but that is no reason to confound them, especially when you are thinking about taxation and redistribution. That is why we want to temper the wind to the shorn lamb, and let it blow on the sable coat.

Robert Solow Journal of Economic Perspectives (2014)

A society where we allow the inequality of incomes and wealth to increase without bounds, sooner or later implodes. The cement that keeps us together erodes and in the end we are only left with people dipped in the ice cold water of egoism and greed.