Axel Leijonhufvud a ‘New Keynesian’? No way! Trying to delineate the difference between ‘New Keynesianism’ and ‘Post Keynesianism’ — during an interview a couple of weeks ago — yours truly was confronted by the odd and confused view that Axel Leijonhufvud was a ‘New Keynesian.’ I wasn’t totally surprised — I had run into that misapprehension before — but still, it’s strange how wrong people sometimes get things. The last time I met Axel, we were both invited keynote speakers at the conference “Keynes 125 Years – What Have We Learned?” in Copenhagen. Axel’s speech was later published as Keynes and the crisis and contains the following thought provoking passages: So far I have argued that recent events should force us to re-examine recent monetary policy doctrine. Do we also need to reconsider modern macroeconomic theory in general? I should think so. Consider briefly a few of the issues. The real interest rate … The problem is that the real interest rate does not exist in reality but is a constructed variable. What does exist is the money rate of interest from which one may construct a distribution of perceived real interest rates given some distribution of inflation expectations over agents. Intertemporal non-monetary general equilibrium (or finance) models deal in variables that have no real world counterparts.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Axel Leijonhufvud a ‘New Keynesian’? No way!

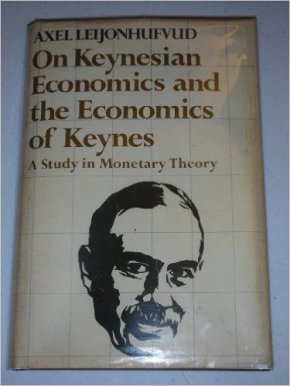

Trying to delineate the difference between ‘New Keynesianism’ and ‘Post Keynesianism’ — during an interview a couple of weeks ago — yours truly was confronted by the odd and confused view that Axel Leijonhufvud was a ‘New Keynesian.’ I wasn’t totally surprised — I had run into that misapprehension before — but still, it’s strange how wrong people sometimes get things.

Trying to delineate the difference between ‘New Keynesianism’ and ‘Post Keynesianism’ — during an interview a couple of weeks ago — yours truly was confronted by the odd and confused view that Axel Leijonhufvud was a ‘New Keynesian.’ I wasn’t totally surprised — I had run into that misapprehension before — but still, it’s strange how wrong people sometimes get things.

The last time I met Axel, we were both invited keynote speakers at the conference “Keynes 125 Years – What Have We Learned?” in Copenhagen. Axel’s speech was later published as Keynes and the crisis and contains the following thought provoking passages:

So far I have argued that recent events should force us to re-examine recent monetary policy doctrine. Do we also need to reconsider modern macroeconomic theory in general? I should think so. Consider briefly a few of the issues.

The real interest rate … The problem is that the real interest rate does not exist in reality but is a constructed variable. What does exist is the money rate of interest from which one may construct a distribution of perceived real interest rates given some distribution of inflation expectations over agents. Intertemporal non-monetary general equilibrium (or finance) models deal in variables that have no real world counterparts. Central banks have considerable influence over money rates of interest as demonstrated, for example, by the Bank of Japan and now more recently by the Federal Reserve …

The representative agent. If all agents are supposed to have rational expectations, it becomes convenient to assume also that they all have the same expectation and thence tempting to jump to the conclusion that the collective of agents behaves as one. The usual objection to representative agent models has been that it fails to take into account well-documented systematic differences in behaviour between age groups, income classes, etc. In the financial crisis context, however, the objection is rather that these models are blind to the consequences of too many people doing the same thing at the same time, for example, trying to liquidate very similar positions at the same time. Representative agent models are peculiarly subject to fallacies of composition. The representative lemming is not a rational expectations intertemporal optimising creature. But he is responsible for the fat tail problem that macroeconomists have the most reason to care about …

For many years now, the main alternative to Real Business Cycle Theory has been a somewhat loose cluster of models given the label of New Keynesian theory. New Keynesians adhere on the whole to the same DSGE modeling technology as RBC macroeconomists but differ in the extent to which they emphasise inflexibilities of prices or other contract terms as sources of shortterm adjustment problems in the economy. The “New Keynesian” label refers back to the “rigid wages” brand of Keynesian theory of 40 or 50 years ago. Except for this stress on inflexibilities this brand of contemporary macroeconomic theory has basically nothing Keynesian about it.

The obvious objection to this kind of return to an earlier way of thinking about macroeconomic problems is that the major problems that have had to be confronted in the last twenty or so years have originated in the financial markets – and prices in those markets are anything but “inflexible”. But there is also a general theoretical problem that has been festering for decades with very little in the way of attempts to tackle it. Economists talk freely about “inflexible” or “rigid” prices all the time, despite the fact that we do not have a shred of theory that could provide criteria for judging whether a particular price is more or less flexible than appropriate to the proper functioning of the larger system. More than seventy years ago, Keynes already knew that a high degree of downward price flexibility in a recession could entirely wreck the financial system and make the situation infinitely worse. But the point of his argument has never come fully to inform the way economists think about price inflexibilities …

I began by arguing that there are three things we should learn from Keynes … The third was to ask whether events provedthat existing theory needed to be revised. On that issue, I conclude that dynamic stochastic general equilibrium theory has shown itself an intellectually bankrupt enterprise. But this does not mean that we should revert to the old Keynesian theory that preceded it (or adopt the New Keynesian theory that has tried to compete with it). What we need to learn from Keynes, instead, are these three lessons about how to view our responsibilities and how to approach our subject.

Axel Leijonhufvud a ‘New Keynesian’? Forget it!