Krugman’s dangerous lack of methodological reflection How do we do useful economics? This is an important question that every earnest economist ought to pose — and try to answer. Here’s one answer, from Nobel laureate Paul Krugman: In general, what we really do is combine maximization-and-equilibrium as a first cut with a variety of ad hoc modifications reflecting what seem to be empirical regularities about how both individual behavior and markets depart from this idealized case. For everyone who knows at least a little of contemporary economics, it’s pretty obvious that this is actually not very different from the way economics is supposed to be advancing according to the New Classical school in Chicago. And just as Chicago boys like Lucas and Sargent, Krugman doesn’t give the slightest hint on when (and how) the the gap between the ‘idealized’ models with their unreal assumptions of perfectly rational individuals and markets gets so big that the models become useless nonsense. One of the most important things that Krugman and other mainstream neoclassical economists trivialize, or do not want to admit, is the ubiquity of genuine uncertainty. And this is, of course, not by chance.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Krugman’s dangerous lack of methodological reflection

How do we do useful economics?

This is an important question that every earnest economist ought to pose — and try to answer.

Here’s one answer, from Nobel laureate Paul Krugman:

In general, what we really do is combine maximization-and-equilibrium as a first cut with a variety of ad hoc modifications reflecting what seem to be empirical regularities about how both individual behavior and markets depart from this idealized case.

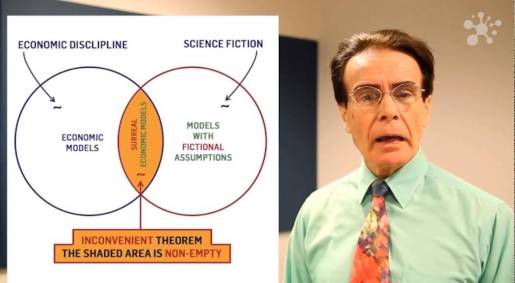

For everyone who knows at least a little of contemporary economics, it’s pretty obvious that this is actually not very different from the way economics is supposed to be advancing according to the New Classical school in Chicago. And just as Chicago boys like Lucas and Sargent, Krugman doesn’t give the slightest hint on when (and how) the the gap between the ‘idealized’ models with their unreal assumptions of perfectly rational individuals and markets gets so big that the models become useless nonsense.

One of the most important things that Krugman and other mainstream neoclassical economists trivialize, or do not want to admit, is the ubiquity of genuine uncertainty. And this is, of course, not by chance. The more uncertainty there is in the economy, the less possibilities are there for any ‘maximization’ going on in any ‘stable equilibria’!

Krugman’s view should come as no surprise for those who took part of Krugman’s response to my critique of IS-LM. Krugman works with a very simple modelling dichotomy — either models are complex or they are simple. For years now, self-proclaimed ‘proud neoclassicist’ Paul Krugman has in endless harpings on the same old IS-LM string told us about the splendour of the Hicksian invention — so, of course, to Krugman simpler models are always preferred.

When it comes to modeling philosophy, Paul Krugman has in an earlier piece defended his position in the following words (my italics):

I don’t mean that setting up and working out microfounded models is a waste of time. On the contrary, trying to embed your ideas in a microfounded model can be a very useful exercise — not because the microfounded model is right, or even better than an ad hoc model, but because it forces you to think harder about your assumptions, and sometimes leads to clearer thinking. In fact, I’ve had that experience several times.

The argument is hardly convincing. If people put that enormous amount of time and energy that they do into constructing macroeconomic models, then they really have to be substantially contributing to our understanding and ability to explain and grasp real macroeconomic processes. If not, they should – after somehow perhaps being able to sharpen our thoughts – be thrown into the waste-paper-basket, and not as today, being allowed to overrun our economics journals and giving their authors celestial academic prestige.

Krugman has in more than one article criticized mainstream economics for using too much (bad) mathematics and axiomatics in their model-building endeavours. But when it comes to defending his own position on various issues he usually himself ultimately falls back on the same kind of models. In his End This Depression Now — just to take one example — Paul Krugman maintains that although he doesn’t buy ‘the assumptions about rationality and markets that are embodied in many modern theoretical models, my own included,’ he still find them useful ‘as a way of thinking through some issues carefully.’

When it comes to methodology and assumptions, Krugman obviously has a lot in common with the kind of model-building he otherwise criticizes.

If macroeconomic models – no matter of what ilk – make assumptions, and we know that real people and markets cannot be expected to obey these assumptions, the warrants for supposing that conclusions or hypotheses of causally relevant mechanisms or regularities can be bridged, are obviously non-justifiable. Macroeconomic theorists – regardless of being New Monetarist, New Classical or ‘New Keynesian’ – ought to do some methodological reflection and heed Keynes’ warnings on using thought-models in economics:

The object of our analysis is, not to provide a machine, or method of blind manipulation, which will furnish an infallible answer, but to provide ourselves with an organized and orderly method of thinking out particular problems; and, after we have reached a provisional conclusion by isolating the complicating factors one by one, we then have to go back on ourselves and allow, as well as we can, for the probable interactions of the factors amongst themselves. This is the nature of economic thinking. Any other way of applying our formal principles of thought (without which, however, we shall be lost in the wood) will lead us into error.