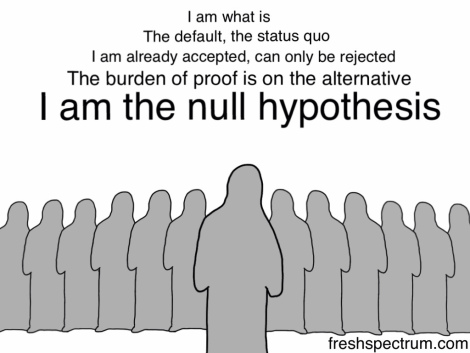

NHST — a case of statistical pseudoscience NHST is an incompatible amalgamation of the theories of Fisher and of Neyman and Pearson (Gigerenzer, 2004). Curiously, it is an amalgamation that is technically reassuring despite it being, philosophically, pseudoscience. More interestingly, the numerous critiques raised against it for the past 80 years have not only failed to debunk NHST from the researcher’s statistical toolbox, they have also failed to be widely known, to find their way into statistics manuals, to be edited out of journal submission requirements, and to be flagged up by peer-reviewers (e.g., Gigerenzer, 2004). NHST effectively negates the benefits that could be gained from Fisher’s and from Neyman-Pearson’s theories; it also slows scientific progress (Savage, 1957; Carver, 1978, 1993) and may be fostering pseudoscience. The best option would be to ditch NHST altogether and revert to the theories of Fisher and of Neyman-Pearson as—and when—appropriate. For everything else, there are alternative tools, among them exploratory data analysis (Tukey, 1977), effect sizes (Cohen, 1988), confidence intervals (Neyman, 1935), meta-analysis (Rosenthal, 1984), Bayesian applications (Dienes, 2014) and, chiefly, honest critical thinking (Fisher, 1960).

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Statistics & Econometrics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Keynes’ critique of econometrics is still valid

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of random walks

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of econometrics

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What statistics teachers get wrong!

NHST — a case of statistical pseudoscience

NHST is an incompatible amalgamation of the theories of Fisher and of Neyman and Pearson (Gigerenzer, 2004). Curiously, it is an amalgamation that is technically reassuring despite it being, philosophically, pseudoscience. More interestingly, the numerous critiques raised against it for the past 80 years have not only failed to debunk NHST from the researcher’s statistical toolbox, they have also failed to be widely known, to find their way into statistics manuals, to be edited out of journal submission requirements, and to be flagged up by peer-reviewers (e.g., Gigerenzer, 2004). NHST effectively negates the benefits that could be gained from Fisher’s and from Neyman-Pearson’s theories; it also slows scientific progress (Savage, 1957; Carver, 1978, 1993) and may be fostering pseudoscience. The best option would be to ditch NHST altogether and revert to the theories of Fisher and of Neyman-Pearson as—and when—appropriate. For everything else, there are alternative tools, among them exploratory data analysis (Tukey, 1977), effect sizes (Cohen, 1988), confidence intervals (Neyman, 1935), meta-analysis (Rosenthal, 1984), Bayesian applications (Dienes, 2014) and, chiefly, honest critical thinking (Fisher, 1960).