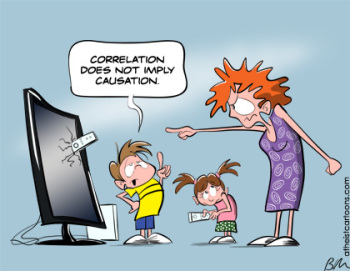

[embedded content] Causality in social sciences — and economics — can never solely be a question of statistical inference. Causality entails more than predictability, and to really in depth explain social phenomena require theory. Analysis of variation — the foundation of all econometrics — can never in itself reveal how these variations are brought about. First when we are able to tie actions, processes or structures to the statistical relations detected, can we say that we are getting at relevant explanations of causation. Most facts have many different, possible, alternative explanations, but we want to find the best of all contrastive (since all real explanation takes place relative to a set of alternatives) explanations. So which is the best explanation? Many

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Statistics & Econometrics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Keynes’ critique of econometrics is still valid

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of random walks

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of econometrics

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What statistics teachers get wrong!

Causality in social sciences — and economics — can never solely be a question of statistical inference. Causality entails more than predictability, and to really in depth explain social phenomena require theory. Analysis of variation — the foundation of all econometrics — can never in itself reveal how these variations are brought about. First when we are able to tie actions, processes or structures to the statistical relations detected, can we say that we are getting at relevant explanations of causation.

Most facts have many different, possible, alternative explanations, but we want to find the best of all contrastive (since all real explanation takes place relative to a set of alternatives) explanations. So which is the best explanation? Many scientists, influenced by statistical reasoning, think that the likeliest explanation is the best explanation. But the likelihood of x is not in itself a strong argument for thinking it explains y. I would rather argue that what makes one explanation better than another are things like aiming for and finding powerful, deep, causal, features and mechanisms that we have warranted and justified reasons to believe in. Statistical — especially the variety based on a Bayesian epistemology — reasoning generally has no room for these kinds of explanatory considerations. The only thing that matters is the probabilistic relation between evidence and hypothesis. That is also one of the main reasons I find abduction — inference to the best explanation — a better description and account of what constitute actual scientific reasoning and inferences.

Most facts have many different, possible, alternative explanations, but we want to find the best of all contrastive (since all real explanation takes place relative to a set of alternatives) explanations. So which is the best explanation? Many scientists, influenced by statistical reasoning, think that the likeliest explanation is the best explanation. But the likelihood of x is not in itself a strong argument for thinking it explains y. I would rather argue that what makes one explanation better than another are things like aiming for and finding powerful, deep, causal, features and mechanisms that we have warranted and justified reasons to believe in. Statistical — especially the variety based on a Bayesian epistemology — reasoning generally has no room for these kinds of explanatory considerations. The only thing that matters is the probabilistic relation between evidence and hypothesis. That is also one of the main reasons I find abduction — inference to the best explanation — a better description and account of what constitute actual scientific reasoning and inferences.

For more on these issues — see the chapter “Capturing causality in economics and the limits of statistical inference” in my On the use and misuse of theories and models in economics.

In the social sciences … regression is used to discover relationships or to disentangle cause and effect. However, investigators have only vague ideas as to the relevant variables and their causal order; functional forms are chosen on the basis of convenience or familiarity; serious problems of measurement are often encountered.

Regression may offer useful ways of summarizing the data and making predictions. Investigators may be able to use summaries and predictions to draw substantive conclusions. However, I see no cases in which regression equations, let alone the more complex methods, have succeeded as engines for discovering causal relationships.

Some statisticians and data scientists think that algorithmic formalisms somehow give them access to causality. That is, however, simply not true. Assuming ‘convenient’ things like faithfulness or stability is not to give proofs. It’s to assume what has to be proven. Deductive-axiomatic methods used in statistics do no produce evidence for causal inferences. The real casuality we are searching for is the one existing in the real-world around us. If their is no warranted connection between axiomatically derived theorems and the real-world, well, then we haven’t really obtained the causation we are looking for.