The government budget deficits obsession The obsession with government budget deficits since the crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recession illustrates the damage done by mistaken economic ideas. In the rich West, tens of millions of people lost jobs that could have been saved … The media focused on the politics of the budget debate, but economic ideas had a central role in the outcome. Believers in Say’s law predominated … The most prominent research was led by Alberto Alesina of Harvard University, where conservative economists had displaced much of the formerly pro-government liberal faculty of the 1960s … Cut deficits, went Alesina’s argument, and you will restore the business confidence to invest fully the excess savings; spending cuts were more

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

The government budget deficits obsession

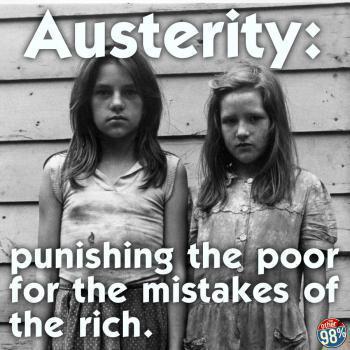

The obsession with government budget deficits since the crisis of 2008 and the subsequent recession illustrates the damage done by mistaken economic ideas. In the rich West, tens of millions of people lost jobs that could have been saved …

The media focused on the politics of the budget debate, but economic ideas had a central role in the outcome. Believers in Say’s law predominated … The most prominent research was led by Alberto Alesina of Harvard University, where conservative economists had displaced much of the formerly pro-government liberal faculty of the 1960s … Cut deficits, went Alesina’s argument, and you will restore the business confidence to invest fully the excess savings; spending cuts were more effective than tax increases in reducing deficits.

Alesina’s research was poor. Most important, his analysis, which started in the early 1990s, didn’t distinguish the economic conditions under which austerity policies were adopted. Essentially, Alesina’s optimistic conclusions about austerity expansions applied only when economies were already strengthening or their currencies were falling in value sufficiently to spur export — conditions not applicable to either the United States or most of Europe.

No matter how much confidence you have in the policies pursued by authorities nowadays, it cannot turn bad austerity policies into good job creating policies. Austerity measures and overzealous and simple-minded fixation on monetary measures and inflation are not what it takes to get our limping economies out of their present day limbo.  They simply do not get us out of the ‘magneto trouble’ — and neither does budget deficit discussions where economists and politicians seem to think that cutting government budgets would help us out of recessions and slumps. In a situation where monetary policies have become more and more decrepit, the solution is not fiscal austerity, but fiscal expansion!

They simply do not get us out of the ‘magneto trouble’ — and neither does budget deficit discussions where economists and politicians seem to think that cutting government budgets would help us out of recessions and slumps. In a situation where monetary policies have become more and more decrepit, the solution is not fiscal austerity, but fiscal expansion!

We are not going to get out of the present economic doldrums as long as we continue to be obsessed with the insane idea that austerity is the universal medicine. When an economy is already hanging on the ropes, you can’t just cut government spendings. Cutting government expenditures reduces the aggregate demand. Lower aggregate demand means lower tax revenues. Lower tax revenues mean increased deficits — and calls for even more austerity. And so on, and so on …