Reasons to reject the standard rationality axioms in economics Those axioms—and you can find a whole series of people from Pareto onwards who make the same argument—come from economists’ introspection and what they think is necessary for their work, not from observation of what people are doing. Some of these axioms seem natural, at least at first sight. For example, transitivity seems a natural idea—if you prefer A to B and B to C, you also prefer A to C. But if you look carefully at how economists define the things over which you are making choices, you could never observe whether or not an individual is making transitive choices. My main problem is that none of these axioms is taken by observing lots and lots of people. In other disciplines, that is what you do. You look and then you try to develop a model which might explain what you observe. In economics, we started out by doing the formalization and building models which were internally consistent but often far removed from reality. To construct models which we could analyse formally, we needed to make some formal assumptions … These assumptions are somehow not natural, they are not about what people do, they are more about what we need in order to pursue our analysis. So that is my real objection.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Reasons to reject the standard rationality axioms in economics

Those axioms—and you can find a whole series of people from Pareto onwards who make the same argument—come from economists’ introspection and what they think is necessary for their work, not from observation of what people are doing.

Some of these axioms seem natural, at least at first sight. For example, transitivity seems a natural idea—if you prefer A to B and B to C, you also prefer A to C. But if you look carefully at how economists define the things over which you are making choices, you could never observe whether or not an individual is making transitive choices.

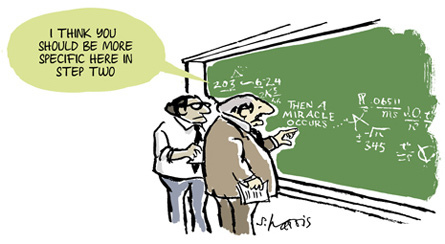

My main problem is that none of these axioms is taken by observing lots and lots of people. In other disciplines, that is what you do. You look and then you try to develop a model which might explain what you observe. In economics, we started out by doing the formalization and building models which were internally consistent but often far removed from reality. To construct models which we could analyse formally, we needed to make some formal assumptions … These assumptions are somehow not natural, they are not about what people do, they are more about what we need in order to pursue our analysis. So that is my real objection.

What do you replace that with? Do you just say that people just make arbitrary random choices? Well of course not. The argument I would make would be that, in some sense, people see directions in which they think their welfare improves, and they try to move in those directions. A simple way to model this is to give simple rules to agents that you find plausible and then look at how that works. In such a model, people are not irrational, but rationality must have a much more open definition …

One of the problems that we find is that people have now somehow absorbed the economist’s notion of rationality, so that when people say ‘rational’, they immediately have in mind something like what economists define as rationality. In fact, rationality can be thought of in many different ways. Rationality for me would mean something more like coherent or interpretable behaviour; behaviour that is not just random.

When back in the 1980s giving graduate courses in microeconomics, Alan Kirman’s books were self-evidently on the reading list.

They still are.