The tragedy of pseudoscientific and self-defeatingly arrogant economics The problem of any branch of knowledge is to systematize a set of particular observations in a more coherent form, called hypothesis or ‘theory.’ Two problems must be resolved by those attempting to develop theory: (1) finding agreement on what has been observed; (2) finding agreement on how to systematize those observations. In economics, there would be more agreement on the second point than on the first. Many would agree that using the short-hand rules of mathematics is a convenient way of systematizing and communicating knowledge — provided we have agreement on the first problem, namely what observations are being systematized. Social sciences face this problem in the absence of controlled experiments in a changing, non-repetitive world. This problem may be more acute for economics than for other branches of social science, because economists like to believe that they are dealing with quantitative facts, and can use standard statistical methods.

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

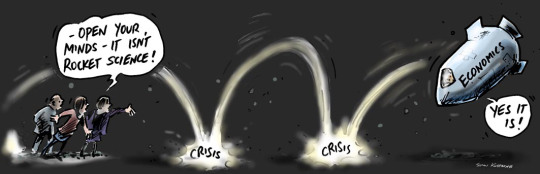

The tragedy of pseudoscientific and self-defeatingly arrogant economics

The problem of any branch of knowledge is to systematize a set of particular observations in a more coherent form, called hypothesis or ‘theory.’ Two problems must be resolved by those attempting to develop theory: (1) finding agreement on what has been observed; (2) finding agreement on how to systematize those observations.

In economics, there would be more agreement on the second point than on the first. Many would agree that using the short-hand rules of mathematics is a convenient way of systematizing and communicating knowledge — provided we have agreement on the first problem, namely what observations are being systematized. Social sciences face this problem in the absence of controlled experiments in a changing, non-repetitive world. This problem may be more acute for economics than for other branches of social science, because economists like to believe that they are dealing with quantitative facts, and can use standard statistical methods. However, what are quantitative facts in a changing world? If one is dealing with questions of general interest that arise in macroeconomics, one has to first agree on ‘robust’ so-called ‘stylized’ facts based on observation: for example, we can agree that business cycles occur; that total output grows as a long term trend; that unemployment and financial crisis are recurring problems, and so on.

In the view of the economic world now dominant in major universities in the United States — with its ripple effect around the world — is these are transient states, aberrations from a perfectly functioning equilibrium system. The function of theory, in this view, is to systematize the perfectly functioning world as a deterministic system with the aid of mathematics. One cannot but be reminded of the great French mathematician Laplace, who claimed with chilling arrogance, two centuries after Newton, that one could completely predict the future and the past on the basis of scientific laws of motion — if only one knew completely the present state of all particles. When emperor Napoleon asked how God fitted into this view, Laplace is said to have replied that he did not need that particular hypothesis. Replace ‘God’ by ‘uncertainty’, and you are pretty close to knowing what mainstream macro-economists in well-known universities are doing with their own variety of temporal and inter-temporal optimization techniques, and their assumption of a representative all knowing, all-seeing rational agent.

Some find this extreme and out-dated scientific determinism difficult to stomach, but are afraid to move too far away, mostly for career reasons. They change assumptions at the margin, but leave the main structure mostly unchallenged. The tragedy of the vast, growing industry of ‘scientific’ knowledge in economics is that students and young researchers are not exposed to alternative views of how problems may be posed and tackled.

Yes indeed — modern economics has become increasingly irrelevant to the understanding of the real world. One of the main reasons for this irrelevance is the failure of economists to match their deductive-axiomatic methods with their subject.

It is still a fact that within mainstream economics internal validity is everything and external validity nothing. Why anyone should be interested in that kind of theories and models is beyond my imagination. As long as mainstream economists do not come up with any export-licenses for their theories and models to the real world in which we live, they really should not be surprised if people say that this is not science, but autism!

Studying mathematics and logics is interesting and fun. But economics is not pure mathematics or logics. It’s about society. The real world. Forgetting that, economics is really in dire straits.

Already back in 1991, a commission chaired by Anne Krueger and including people like Kenneth Arrow, Edward Leamer, and Joseph Stiglitz, reported from own experience “that it is an underemphasis on the ‘linkages’ between tools, both theory and econometrics, and ‘real world problems’ that is the weakness of graduate education in economics,” and that both students and faculty sensed “the absence of facts, institutional information, data, real-world issues, applications, and policy problems.” And in conclusion they wrote that “graduate programs may be turning out a generation with too many idiot savants skilled in technique but innocent of real economic issues.”

Not much is different today. Economics — and economics education — is still in dire need of a remake.