The pitfalls of econometrics Ed Leamer’s Tantalus on the Road to Asymptopia is one of my favourite critiques of econometrics, and for the benefit of those who are not versed in the econometric jargon, this handy summary gives the gist of it in plain English: Most work in econometrics and regression analysis is made on the assumption that the researcher has a theoretical model that is ‘true.’ Based on this belief of having a correct specification for an econometric model or running a regression, one proceeds as if the only problem remaining to solve have to do with measurement and observation. When things sound to good to be true, they usually aren’t. And that goes for econometric wet dreams too. The snag is, as Leamer convincingly argues, that there is

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Statistics & Econometrics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Keynes’ critique of econometrics is still valid

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of random walks

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of econometrics

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What statistics teachers get wrong!

The pitfalls of econometrics

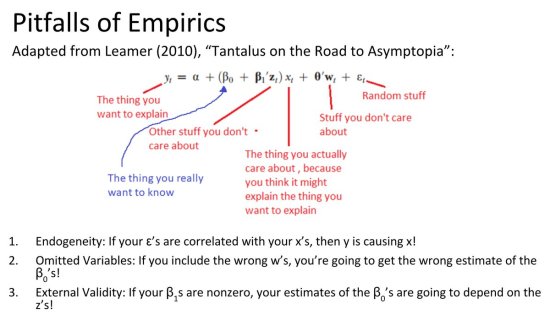

Ed Leamer’s Tantalus on the Road to Asymptopia is one of my favourite critiques of econometrics, and for the benefit of those who are not versed in the econometric jargon, this handy summary gives the gist of it in plain English:

Most work in econometrics and regression analysis is made on the assumption that the researcher has a theoretical model that is ‘true.’ Based on this belief of having a correct specification for an econometric model or running a regression, one proceeds as if the only problem remaining to solve have to do with measurement and observation.

When things sound to good to be true, they usually aren’t. And that goes for econometric wet dreams too. The snag is, as Leamer convincingly argues, that there is pretty little to support the perfect specification assumption. Looking around in social science and economics we don’t find a single regression or econometric model that lives up to the standards set by the ‘true’ theoretical model — and there is pretty little that gives us reason to believe things will be different in the future.

When things sound to good to be true, they usually aren’t. And that goes for econometric wet dreams too. The snag is, as Leamer convincingly argues, that there is pretty little to support the perfect specification assumption. Looking around in social science and economics we don’t find a single regression or econometric model that lives up to the standards set by the ‘true’ theoretical model — and there is pretty little that gives us reason to believe things will be different in the future.

To think that we are being able to construct a model where all relevant variables are included and correctly specify the functional relationships that exist between them, is not only a belief without support, but a belief impossible to support. The theories we work with when building our econometric models are insufficient. No matter what we study, there are always some variables missing, and we don’t know the correct way to functionally specify the relationships between the variables we choose to put into our models.

Every econometric model constructed is misspecified. There are always an endless list of possible variables to include, and endless possible ways to specify the relationships between them. So every applied econometrician comes up with his own specification and parameter estimates. The econometric Holy Grail of consistent and stable parameter-values is nothing but a dream.

A rigorous application of econometric methods presupposes that the phenomena of our real world economies are ruled by stable causal relations between variables. Parameter-values estimated in specific spatio-temporal contexts are presupposed to be exportable to totally different contexts. To warrant this assumption one, however, has to convincingly establish that the targeted acting causes are stable and invariant so that they maintain their parametric status after the bridging. The endemic lack of predictive success of the econometric project indicates that this hope of finding fixed parameters is a hope for which there really is no other ground than hope itself.

The theoretical conditions that have to be fulfilled for regression analysis and econometrics to really work are nowhere even closely met in reality. Making outlandish statistical assumptions does not provide a solid ground for doing relevant social science and economics. Although regression analysis and econometrics have become the most used quantitative methods in social sciences and economics today, it’s still a fact that the inferences made from them are, strictly seen, invalid.

Econometrics is basically a deductive method. Given the assumptions (such as manipulability, transitivity, separability, additivity, linearity, etc) it delivers deductive inferences. The problem, of course, is that we will never completely know when the assumptions are right. Conclusions can only be as certain as their premises. That also applies to econometrics.