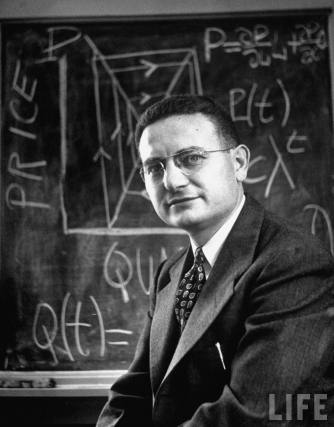

Paul Samuelson and the ergodic hypothesis Paul Samuelson claimed that the “ergodic hypothesis” is essential for advancing economics from the realm of history to the realm of science. But is it really tenable to assume that ergodicity is essential to economics? The answer can only be – as I have argued here here here here and here – NO WAY! Obviously yours truly is far from the only scientist being critical of Paul Samuelson. This is what Ole Peters writes in a highly interesting article on Samuelson’s stance on the ergodic hypothesis: Samuelson said that we should accept the ergodic hypothesis because if a system is not ergodic you cannot treat it scientifically. First of all, that’s incorrect, although I think I understand how he ended up with this

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Paul Samuelson and the ergodic hypothesis

Paul Samuelson claimed that the “ergodic hypothesis” is essential for advancing economics from the realm of history to the realm of science.

Paul Samuelson claimed that the “ergodic hypothesis” is essential for advancing economics from the realm of history to the realm of science.

But is it really tenable to assume that ergodicity is essential to economics?

The answer can only be – as I have argued

and

here – NO WAY!

Obviously yours truly is far from the only scientist being critical of Paul Samuelson. This is what Ole Peters writes in a highly interesting article on Samuelson’s stance on the ergodic hypothesis:

Samuelson said that we should accept the ergodic hypothesis because if a system is not ergodic you cannot treat it scientifically. First of all, that’s incorrect, although I think I understand how he ended up with this impression: ergodicity means that a system is very insensitive to initial conditions or perturbations and details of the dynamics, and that makes it easy to make universal statements about such systems …

Another problem with Samuelson’s statement is the logic: we should accept this hypothesis because then we can make universal statements. But before we make any hypothesis—even one that makes our lives easier—we should check whether we know it to be wrong. In this case, there’s nothing to hypothesize. Financial and economic systems are non-ergodic. And if that means we can’t say anything meaningful, then perhaps we shouldn’t try to make meaningful claims. Well, perhaps we can speak for entertainment, but we cannot claim that it’s meaningful.

In what sense would saying something that’s patently false be “meaningful,” or “scientific” rather than “historical”? You can see where I’m going with this. Important models that economists use are not ergodic, so what’s this debate about?…

Samuelson’s comment makes little sense. A hypothesis is about something we don’t know, but in the case of finance models this is something we do know. There’s no reason to hypothesize—the system is not ergodic. It’s like hypothesizing that 3 times 4 is 0 because it makes the mathematics simpler. But I can calculate that the product is 12. Of course, a formalism that’s based on the 3-times-4 hypothesis will run into trouble sooner or later. In economics, that happens with the ergodic hypothesis when we think about risk, or financial stability. Or inequality, as we’re just working out at the moment.

And this is Nassim Taleb’s verdict on Samuelson’s view on science:

However, if you believe in free will you can’t truly believe in social science and economic projection. You cannot predict how people will act. Except, of course, if there is a trick, and that trick is the cord on which neoclassical economics is suspended. You simply assume that individuals will be rational in the future and thus act predictably. There is a strong link between rationality, predictability, and mathematical tractability …

In orthodox economics, rationality became a straitjacket … This led to mathematical techniques such as “maximization,” or “optimization,” on which Paul Samuelson built much of his work … This optimization set back social science by reducing it from the intellectual and reflective discipline that it was becoming to an attempt at an “exact science.” By “exact science,” I mean a second-rate engineering problem for those who want to pretend that they are in the physics department— so-called physics envy. In other words, an intellectual fraud …

The tragedy is that Paul Samuelson, a quick mind, is said to be one of the most intelligent scholars of his generation. This was clearly a case of very badly invested intelligence. Characteristically, Samuelson intimidated those who questioned his techniques with the statement “Those who can, do science, others do methodology.” If you knew math, you could “do science” … Alas, it turns out that it was Samuelson and most of his followers who did not know much math, or did not know how to use what math they knew, how to apply it to reality. They only knew enough math to be blinded by it.

Tragically, before the proliferation of empirically blind idiot savants, interesting work had been begun by true thinkers, the likes of J . M . Keynes, Friedrich Hayek, and the great Benoît Mandelbrot, all of whom were displaced because they moved economics away from the precision of second-rate physics. Very sad.