In Radical Uncertainty, John Kay and Mervyn King, two well-known British economists, state that rather than trying to understand the ever-changing, uncertain and ambiguous environment by trying to understand “what’s going on here”, the economics profession has become dominated by an approach to uncertainty that requires a comprehensive list of possible outcomes with well-defined numerical probabilities attached to them. Drawing widely on philosophy, anthropology, economics, cognitive science, and strategic management and organisation scholarship, the authors present an argument that probabilistic thinking gives us a false understanding of our power to make predictions and a false illusion of utility-maximising behaviour. Instead of trying to produce probability calculations

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

In Radical Uncertainty, John Kay and Mervyn King, two well-known British economists, state that rather than trying to understand the ever-changing, uncertain and ambiguous environment by trying to understand “what’s going on here”, the economics profession has become dominated by an approach to uncertainty that requires a comprehensive list of possible outcomes with well-defined numerical probabilities attached to them. Drawing widely on philosophy, anthropology, economics, cognitive science, and strategic management and organisation scholarship, the authors present an argument that probabilistic thinking gives us a false understanding of our power to make predictions and a false illusion of utility-maximising behaviour. Instead of trying to produce probability calculations to fill the unknown gaps in our knowledge, we should embrace uncertainty by adopting robust and resilient strategies and narratives to consider alternative futures and deal with unpredictable events …

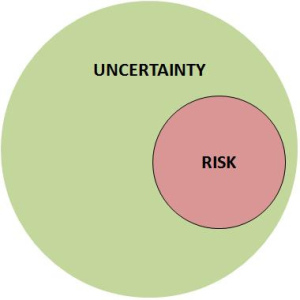

The authors’ “radical uncertainty” is not about “long tails” (for example, imaginable and well-defined events whose low probability can be estimated). The authors emphasise the vast range of possibilities that lie in between the world of unlikely events which can nevertheless be described with the aid of probability distributions, and the world of the unimaginable. This is the world of uncertain futures and unpredictable consequences, about which there is necessary speculation and inevitable disagreement which often will never be resolved. In real life this is the world which we mostly encounter, and it extends to individual and collective decisions, as well as financial, economic and political ones.

Kay and King’s book is a thoughtful and welcome call for economists and policymakers to accept “radical uncertainty” and start rethinking their models.

The financial crisis of 2007-2008 hit most laymen and economists with surprise. What was it that went wrong with our macroeconomic models, since they obviously did not foresee the collapse or even made it conceivable?

There are many who have ventured to answer that question. And they have come up with a variety of answers, ranging from the exaggerated mathematization of economics to irrational and corrupt politicians.

But the root of our problem goes much deeper. It ultimately goes back to how we look upon the data we are handling. In ‘modern’ macroeconomics — Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium, New Synthesis, New Classical and New ‘Keynesian’ — variables are treated as if drawn from a known “data-generating process” that unfolds over time and on which we, therefore, have access to heaps of historical time-series. If we do not assume that we know the ‘data-generating process’ – if we do not have the ‘true’ model – the whole edifice collapses. And of course, it has to. I mean, who honestly believes that we should have access to this mythical Holy Grail, the data-generating process?

But the root of our problem goes much deeper. It ultimately goes back to how we look upon the data we are handling. In ‘modern’ macroeconomics — Dynamic Stochastic General Equilibrium, New Synthesis, New Classical and New ‘Keynesian’ — variables are treated as if drawn from a known “data-generating process” that unfolds over time and on which we, therefore, have access to heaps of historical time-series. If we do not assume that we know the ‘data-generating process’ – if we do not have the ‘true’ model – the whole edifice collapses. And of course, it has to. I mean, who honestly believes that we should have access to this mythical Holy Grail, the data-generating process?

‘Modern’ macroeconomics obviously did not anticipate the enormity of the problems that unregulated ‘efficient’ financial markets created. Why? Because it builds on the myth of us knowing the ‘data-generating process’ and that we can describe the variables of our evolving economies as drawn from an urn containing stochastic probability functions with known means and variances.

This is like saying that you are going on a holiday trip and that you know that the chance the weather being sunny is at least 30% and that this is enough for you to decide on bringing along your sunglasses or not. You are supposed to be able to calculate the expected utility based on the given probability of sunny weather and make a simple decision of either-or. Uncertainty is reduced to risk.

This is like saying that you are going on a holiday trip and that you know that the chance the weather being sunny is at least 30% and that this is enough for you to decide on bringing along your sunglasses or not. You are supposed to be able to calculate the expected utility based on the given probability of sunny weather and make a simple decision of either-or. Uncertainty is reduced to risk.

But as Keynes convincingly argued in his monumental Treatise on Probability (1921), this is not always possible. Often we simply do not know. According to one model the chance of sunny weather is perhaps somewhere around 10% and according to another – equally good – model the chance is perhaps somewhere around 40%. We cannot put exact numbers on these assessments. We cannot calculate means and variances. There are no given probability distributions that we can appeal to.

In the end, this is what it all boils down to. We all know that many activities, relations, processes, and events are of the Keynesian uncertainty-type. The data do not unequivocally single out one decision as the only ‘rational’ one. Neither the economist nor the deciding individual can fully pre-specify how people will decide when facing uncertainties and ambiguities that are ontological facts of the way the world works.

Some macroeconomists, however, still want to be able to use their hammer. So they decide to pretend that the world looks like a nail, and pretend that uncertainty can be reduced to risk. So they construct their mathematical models on that assumption. The result: financial crises and economic havoc.

How much better — how much bigger chance that we do not lull us into the comforting thought that we know everything and that everything is measurable and we have everything under control — if instead, we could just admit that we often simply do not know and that we have to live with that uncertainty as well as it goes.

Fooling people into believing that one can cope with an unknown economic future in a way similar to playing at the roulette wheels, is a sure recipe for only one thing — economic disaster.