Laplace’s rule of succession and Bayesian priors After their first night in paradise, and having seen the sun rise in the morning, Adam and Eve was wondering if they were to experience another sunrise or not. Given the rather restricted sample of sunrises experienced, what could they expect? According to Laplace’s rule of succession, the probability of an event E happening after it has occurred n times is p(E|n) = (n+1)/(n+2). The probabilities can be calculated using Bayes’ rule, but to get the calculations going, Adam and Eve must have an a priori probability (a base rate) to start with. The Bayesian rule of thumb is to simply assume that all outcomes are equally likely. Applying this rule Adam’s and Eve’s probabilities become 1/2, 2/3, 3/4 … Now this

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Statistics & Econometrics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Keynes’ critique of econometrics is still valid

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of random walks

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The history of econometrics

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What statistics teachers get wrong!

Laplace’s rule of succession and Bayesian priors

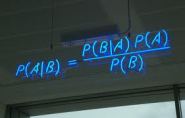

After their first night in paradise, and having seen the sun rise in the morning, Adam and Eve was wondering if they were to experience another sunrise or not. Given the rather restricted sample of sunrises experienced, what could they expect? According to Laplace’s rule of succession, the probability of an event E happening after it has occurred n times is p(E|n) = (n+1)/(n+2).

After their first night in paradise, and having seen the sun rise in the morning, Adam and Eve was wondering if they were to experience another sunrise or not. Given the rather restricted sample of sunrises experienced, what could they expect? According to Laplace’s rule of succession, the probability of an event E happening after it has occurred n times is p(E|n) = (n+1)/(n+2).

The probabilities can be calculated using Bayes’ rule, but to get the calculations going, Adam and Eve must have an a priori probability (a base rate) to start with. The Bayesian rule of thumb is to simply assume that all outcomes are equally likely. Applying this rule Adam’s and Eve’s probabilities become 1/2, 2/3, 3/4 …

The probabilities can be calculated using Bayes’ rule, but to get the calculations going, Adam and Eve must have an a priori probability (a base rate) to start with. The Bayesian rule of thumb is to simply assume that all outcomes are equally likely. Applying this rule Adam’s and Eve’s probabilities become 1/2, 2/3, 3/4 …

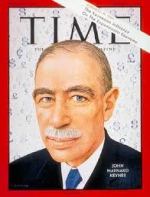

Now this might seem rather straight forward, but as already e. g. Keynes (1921) noted in his Treatise on Probability, there might be a problem here. The problem has to do with the prior probability and where it is assumed to come from. Is the appeal of the principle of insufficient reason — the principle of indifference — really warranted?

Now this might seem rather straight forward, but as already e. g. Keynes (1921) noted in his Treatise on Probability, there might be a problem here. The problem has to do with the prior probability and where it is assumed to come from. Is the appeal of the principle of insufficient reason — the principle of indifference — really warranted?

Assume there is a certain quantity of liquid containing wine and water mixed so that the ratio of wine to water (r) is between 1/3 and 3/1. What is then the probability that r ≤ 2? The principle of insufficient reason means that we have to treat all r-values as equiprobable, assigning a uniform probability distribution between 1/3 and 3/1, which gives the probability of r ≤ 2 = [(2-1/3)/(3-1/3)] = 5/8.

But to say r ≤ 2 is equivalent to saying that 1/r ≥ ½. Applying the principle now, however, gives the probability of 1/r ≥ 1/2 = [(3-1/2)/(3-1/3)]=15/16. So we seem to get two different answers that both follow from the same application of the principle of insufficient reason. Given this unsolved paradox, we have reason to stick with Keynes and be skeptical of Bayesianism.