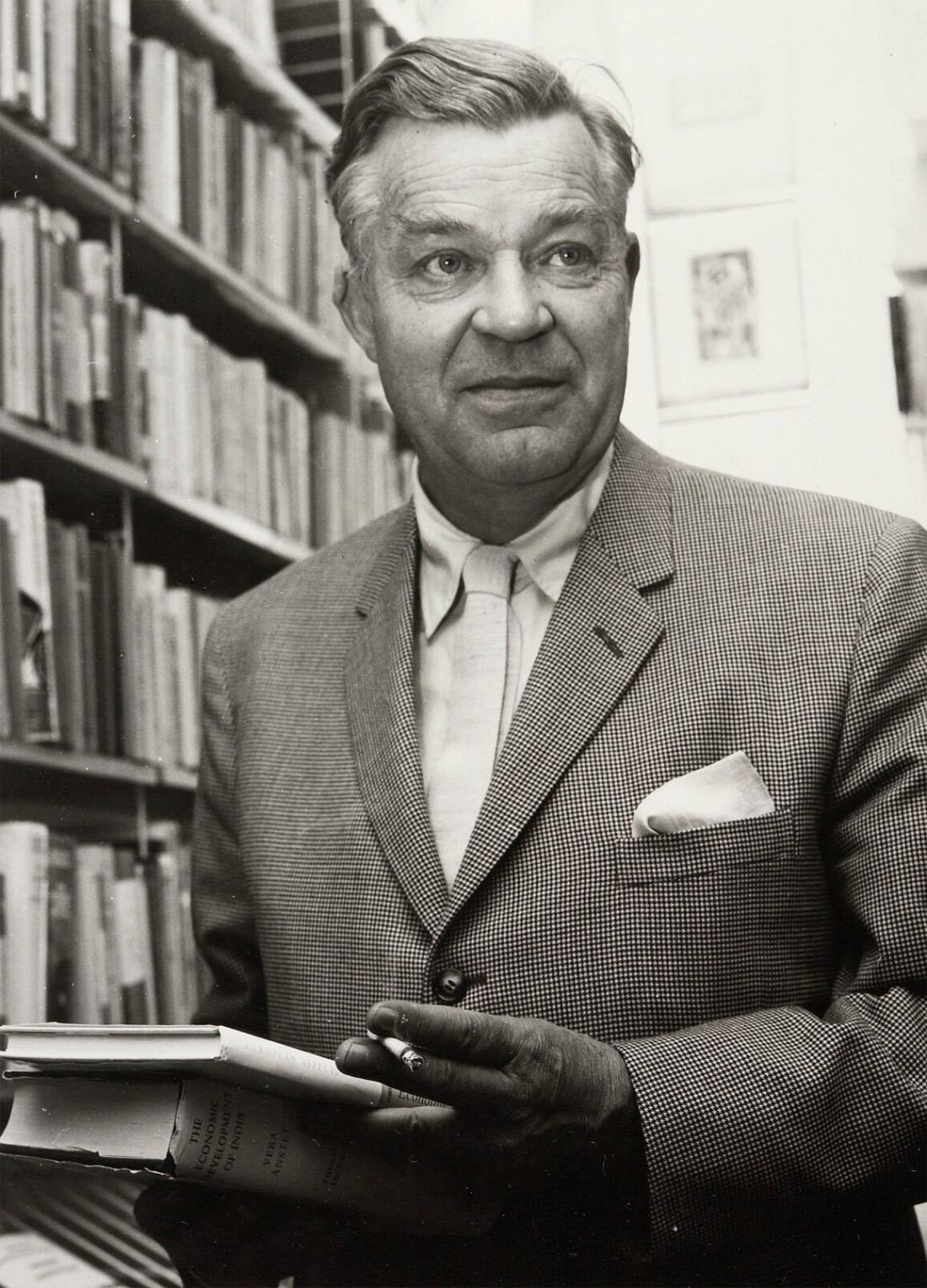

Gunnar Myrdal’s ‘immanent critique’ of utility theory During the time period from 1925 to 1933 — when he still considered himself a ‘central-theoretician’ and a ‘pure economic theorist’ — Gunnar Myrdal wanted to apply to economic doctrines an ‘immanent method’ of criticism. His main interest was to criticize the received economic theory that had preserved structures of normative speculation built upon the concepts of utility and welfare. Many have tried to assess Myrdal’s contribution to social sciences and economics, Brinley Thomas (1936), Tord Palander (1953), Karl Gustav Landgren (1960), George Shackle (1967), Erik Lundberg (1974), Paul Streeten (1979), and Gilles Dostaler (1990) perhaps being the most well known. They however mostly discuss Myrdal’s

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Gunnar Myrdal’s ‘immanent critique’ of utility theory

Many have tried to assess Myrdal’s contribution to social sciences and economics, Brinley Thomas (1936), Tord Palander (1953), Karl Gustav Landgren (1960), George Shackle (1967), Erik Lundberg (1974), Paul Streeten (1979), and Gilles Dostaler (1990) perhaps being the most well known. They however mostly discuss Myrdal’s contributions to monetary equilibrium analysis and economic policy and miss a discussion of what was one of Myrdal’s main concerns up until at least 1931 — a critique of utility theory. Although perhaps little known today, Myrdal wrote quite extensively on this special line of criticism during the period. Partly based on some previously unpublished material, yours truly has described and posited this critique in an essay published in History of Political Economy

In his early career — under the strong influence of the Uppsala philosopher Axel Hägerström and the economist Gustav Cassel — Myrdal questioned the received opinion of the economic establishment. Economists often thought they drew political recommendations from value-free theories. Myrdal argued that this was not the case and that it was important to clarify the value judgments implicitly used and to separate economic policy from economic analysis. Many of the ideas he presented in his theoretical works during this period — such as the difference between ex ante and ex post, the role of uncertainty and expectations, the problem of value premises and normative elements — became cornerstones of his later, more institutional and sociological, studies.

Positive economics was not value-free and often lacked empirical basis. This was especially obvious in marginal utility theory, with its lack of thorough theoretical reflection. Already in his 1927 dissertation —Prisbildningsproblemet och föränderligheten — Myrdal attacked the theory mainly from a methodological point of view, arguing that psychology had to be subordinated to a primary price formation explanation. Later, he rather meant that economic analysis presupposes scientific psychology, but that marginal utility theory, both in its old hedonistic ‘pleasure’ and ‘pain’ form and in its new choice-theoretic form, was a circular construction without foundation in such psychology.

As John Hicks noted in his review of Myrdal’s 1953 book The Political Element in the Development of Economic Theory, Myrdal’s critique was a derivation from Cassel, whose rejection of cardinal utility was extended by Myrdal into “a thoroughgoing rejection of subjective valuation theory altogether.” This, according to Hicks, was also one of the sources of his “extremism.” This was a source on which Myrdal had quite strong beliefs and wrote extensively during the period. It was a central part of his early scientific economic writings, which contained many elements of his later, mainly institutional, works and played an important role in the development of the Stockholm School of Economics. Myrdal’s penetrating critique of the neoclassical theory of value is yet today relevant to economists critically evaluating mainstream economic theory.