We’ve lots of evidence from different times and places that the elasticity of output with respect to capital is indeed small. In his famous paper which kickstarted this approach to thinking about economic growth, Robert Solow estimated (pdf) that only one-eighth of the increase in US GDP per worker between 1900 and 1949 was due to increases in the capital stock. The rest, he said, was due to technical progress. In Fully Grown, Dietrich Vollrath estimated that from 1950 to 2000 a rise in the US’s physical capital stock per person accounted for only 0.64 percentage points of the 2.2 per cent annual rise in real GDP per capita. Nick Crafts has estimated (pdf) that less than one-third of growth in advanced economies between 1913 and 1973 was due to a bigger capital stock. And

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

We’ve lots of evidence from different times and places that the elasticity of output with respect to capital is indeed small. In his famous paper which kickstarted this approach to thinking about economic growth, Robert Solow estimated (pdf) that only one-eighth of the increase in US GDP per worker between 1900 and 1949 was due to increases in the capital stock. The rest, he said, was due to technical progress. In Fully Grown, Dietrich Vollrath estimated that from 1950 to 2000 a rise in the US’s physical capital stock per person accounted for only 0.64 percentage points of the 2.2 per cent annual rise in real GDP per capita. Nick Crafts has estimated (pdf) that less than one-third of growth in advanced economies between 1913 and 1973 was due to a bigger capital stock. And Gavan Conlon and colleagues have estimated (pdf) that a fall in capital growth accounted for less than half of the slowdown in the UK’s hourly productivity growth between 2001-07 and 2014-19.

Now, we shouldn’t be fixated on precise numbers here. Aggregate production functions and measures of both the capital stock and depreciation have massive theoretical and practical problems: Solow himself said that such measures “will really drive a purist mad.” But the picture here is clear: it takes a lot of capital spending to deliver only moderate increases in GDP.

Adam Smith once wrote that a really good explanation is “practically seamless.”

Is there any such theory within one of the most important fields of social sciences — economic growth?

Paul Romer’s theory presented in Endogenous Technological Change (1990) — where knowledge is made the most important driving force of growth — is probably as close as we get.

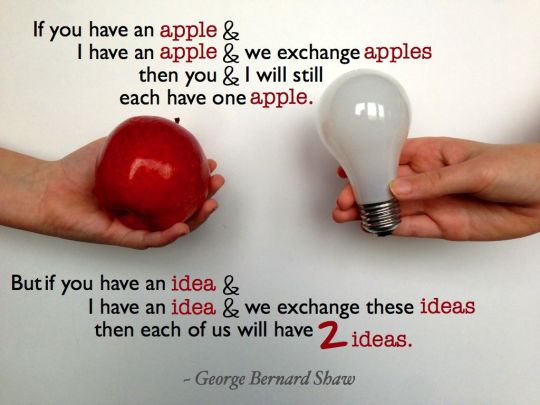

Knowledge — or ideas — are according to Romer the locomotive of growth. But as Allyn Young, Piero Sraffa and others had shown already in the 1920s, knowledge is also something that has to do with increasing returns to scale and therefore not really compatible with mainstream economics with its emphasis on decreasing returns to scale.

Mainstream economics has tried to save itself by more or less substituting human capital for knowledge/ideas. But Romer’s pathbreaking ideas should not be confused with human capital. Although some have problems with the distinction between ideas and human capital in modern endogenous growth theory, this passage from Romer’s article The New Kaldor Facts: Ideas, Institutions, Population, and Human Capital gives a succinct and accessible account of the difference:

The distinction between rival and nonrival goods is easy to blur at the aggregate level but inescapable in any microeconomic setting. Picture, for example, a house that is under construction. The land on which it sits, capital in the form of a measuring tape, and the human capital of the carpenter are all rival goods. They can be used to build this house but not simultaneously any other. Contrast this with the Pythagorean Theorem, which the carpenter uses implicitly by constructing a triangle with sides in the proportions of 3, 4 and 5. This idea is nonrival. Every carpenter in the world can use it at the same time to create a right angle.

Of course, human capital and ideas are tightly linked in production and use. Just as capital produces output and forgone output can be used to produce capital, human capital produces ideas and ideas are used in the educational process to produce human capital. Yet ideas and human capital are fundamentally distinct. At the micro level, human capital in our triangle example literally consists of new connections between neurons in a carpenter’s head, a rival good. The 3-4-5 triangle is the nonrival idea. At the macro level, one cannot state the assertion that skill-biased technical change is increasing the demand for education without distinguishing between ideas and human capital.

Monopolistic competition, product differentiation and increasing returns — generated by e. g. nonrivalry between ideas — are simply not compatible with pure competition and the simplistic invisible hand dogma. Pretending that increasing returns are possible to seamlessly incorporate into the received paradigm, mainstream economics textbook writers transmogrify truth.