Reconsidering Central Bank Independence For anyone naive enough to believe that Central Bank governors’ work is based on solid evidence-based science — forget it! What the newly broadcasted Swedish documentary Debt Fever convincingly demonstrates is that the work of Central Bank governors is little more than subtle storytelling charlatanry—and they know it themselves! In the documentary, Financial Times journalist Gillian Tett describes the work of central banks as nothing but “subtle charlatanry.” Even though central bank governors want to present their work as if it is based on solid science, in reality, it is more about illusions and myths — something also confirmed by Sweden’s former Central Bank governor, Stefan Ingves, when he describes his

Topics:

Lars Pålsson Syll considers the following as important: Economics

This could be interesting, too:

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Schuldenbremse bye bye

Lars Pålsson Syll writes What’s wrong with economics — a primer

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Krigskeynesianismens återkomst

Lars Pålsson Syll writes Finding Eigenvalues and Eigenvectors (student stuff)

Reconsidering Central Bank Independence

For anyone naive enough to believe that Central Bank governors’ work is based on solid evidence-based science — forget it!

In the documentary, Financial Times journalist Gillian Tett describes the work of central banks as nothing but “subtle charlatanry.” Even though central bank governors want to present their work as if it is based on solid science, in reality, it is more about illusions and myths — something also confirmed by Sweden’s former Central Bank governor, Stefan Ingves, when he describes his societal role as a kind of “storytelling uncle.”

When questioned about the Central Bank’s highly flawed forecasts, he responds: “The alternative would be to say that we have no idea about anything.”

“The alternative would be to say that we have no idea about anything.”

Yes—and that would have been a much more intellectually honest answer!

Economists often claim that it doesn’t matter much if the assumptions their models are based on are realistic or not. What matters is whether the predictions the models produce turn out to be correct.

If that is truly the case, the only conclusion we can draw is that these models and predictions belong in the trash bin. Because wow, have they been wrong!

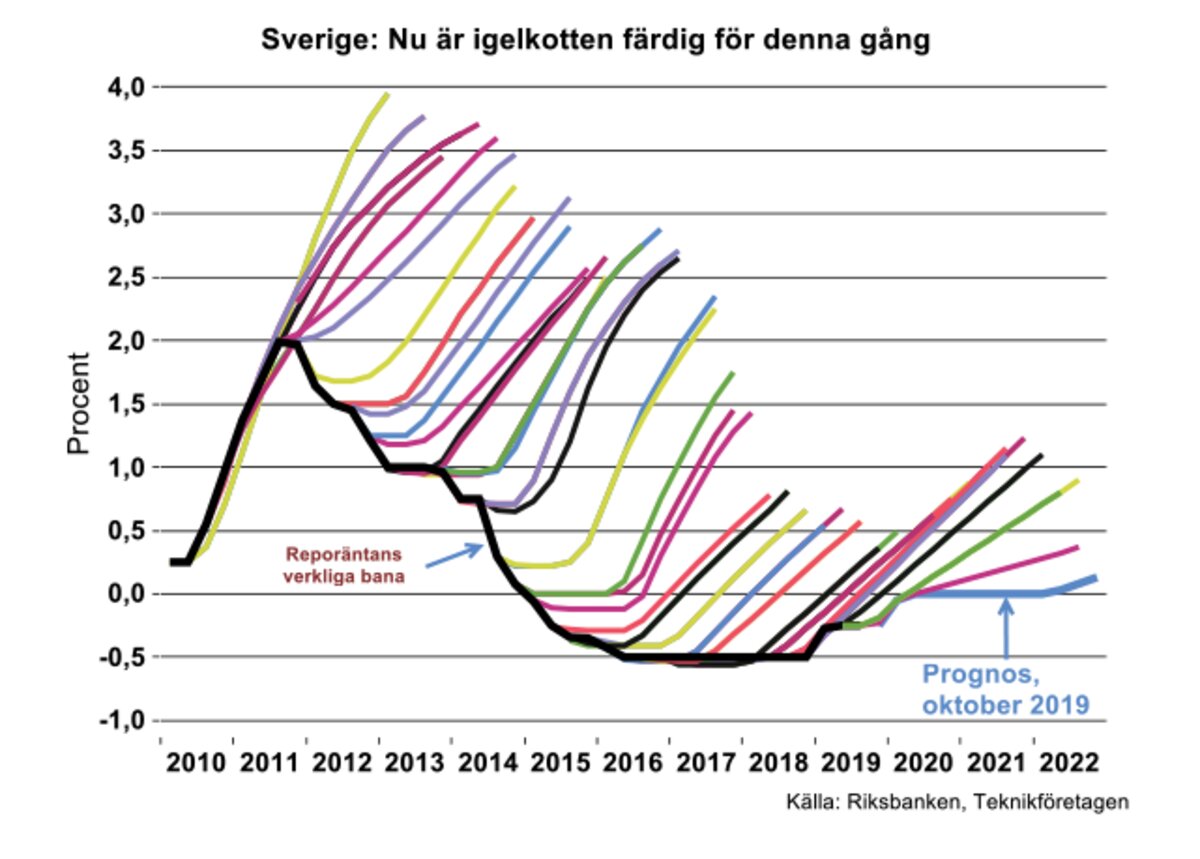

Since 2007, the Swedish Central Bank — Riksbanken — has used so-called ‘interest rate paths’ as forecasting tools. The impact has been significant — even though it is easy to see that the forecasts have consistently been wildly inaccurate. Like most other forecasters, the Central Bank failed to predict both the 2007 financial crisis and its severe consequences. Even in recent years, the Central Bank’s interest rate and inflation forecasts have proven to be terrible.

The so-called ‘interest rate hedgehog’ shows the actual development of interest rates and the Central Bank’s forecasts for them. As we can see, the forecasts have rarely, if ever, been correct.

The so-called ‘interest rate hedgehog’ shows the actual development of interest rates and the Central Bank’s forecasts for them. As we can see, the forecasts have rarely, if ever, been correct.

In other words—these arrogantly self-assured economists with their ‘rigorous’ and ‘precise’ mathematical-statistical models have been consistently wrong. And it is all of us who pay for it!

This is serious. Adding to this is the fact that solid empirical evidence supporting the argument that independent Central Banks are beneficial for the economy is non-existent.

Central Banks have almost unchecked power over monetary policy—a policy that significantly influences inflation, employment, and economic stability. This power should be subject to greater democratic oversight to ensure it aligns with the interests of us as citizens. Over time, Central Banks seem to have developed a kind of ‘policy bias’ where inflation control is prioritized over unemployment and welfare, which appears deeply offensive to large segments of society.

For those who believe that doubts about Central Bank independence are some kind of typically heterodox view, allow me, as a historian of economic theories, to remind you that the idea’s originator—Milton Friedman—himself expressed doubts about the effectiveness of Central Bank independence, particularly concerning its ability to consistently maintain sound monetary policy. Although Friedman generally advocated monetary stability and was critical of arbitrary government interventions, he was sceptical that Central Bank independence would automatically lead to better outcomes. If nothing else, the most recent major financial system crisis (2007–2010) demonstrated that Friedman’s doubts were more than justified.

There is also — on a deeper level — a fundamental problem in the perspective on what decisions and considerations should guide how we act in economically relevant policy issues. If we constitutionally and democratically decide that we want to prioritize fairness, welfare, and jobs over a given inflation target, it is hard to see why we should be bound by an institution that imposes a more extreme ‘economistic’ choice through a regulatory framework designed precisely for that purpose. We must not forget that economics is not always a trump card in policy issues. This should be obvious, but economists in particular often forget it. From an ‘economistic” perspective, one could surely argue that it is economically more profitable to reinstate death cliffs (ättestupan) than to expand costly eldercare. But who would seriously advocate or accept such a thing? Sometimes, other aspects weigh more heavily than purely economic ones.

Beyond the ‘democracy aspects’ of Central Bank independence, there are also good reasons—especially given the striking failures over the past two decades to achieve inflation targets—to question the competence of Central Banks. International research has also convincingly shown that the empirical evidence supporting the argument that independent central banks benefit the economy is virtually non-existent.

Most Central Banks nowadays have essentially only one tool at their disposal—interest rates. And yes, one can use that ‘hammer’ to try to combat the price spiral. But if history has taught us anything, it is that this is likely to succeed only at the cost of increased unemployment and reduced welfare.

Economics as a science has lost an incredible amount of prestige and status worldwide in recent years. Not least due to its inability to analyze and explain economic and financial crises, and because of its lack of constructive and sustainable proposals to help us out of these crises.

If we are to rebuild trust in the science of economics, we must stop pretending that we have precise and accurate answers to everything. Because we don’t. We build models and theories where we can predict to the hundredth of a percentage point what the interest rate will be thirty years from now. We can calculate investment risks and make precise future forecasts. But this is based on mathematical and statistical assumptions that often have very little or nothing to do with reality. By ignoring the crucial difference between model and reality, we lull people into a false sense of security that we have everything under control. We do not! It was this false sense of security that actively contributed to the financial crisis in 2008.

We must dare to admit that sometimes we do not know everything and that there are things we do not even know that we do not know.

In the field of economic policy, we must stop building models and forecasts based on completely unrealistic models with robot-like optimizing humans equipped with ‘rational expectations.’ This is pure nonsense. We must build our models on assumptions that do not stand in harmful contrast to reality. And in that work, we must also be humble enough to admit that psychology and other behavioural sciences can contribute important pieces of the puzzle.