David Fields (Guest blogger)Rising housing costs and stagnating real wages are the primary causes of worsening housing affordability in Utah. The dismal wage growth is the result of a larger nationwide upward redistribution of wealth and income, which can be attributed to the following: a failure to adhere to full employment objectives; fiscal austerity; and various labor market policies and business practices allowing the higher social strata of a professional class to capture ever larger shares of economic growth. This is the result of institutional transformations that have exposed workers to the vulnerability of higher turnover, resulting in higher averages of unemployment, particularly worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic induced recession. For instance, from 2009 to 2016 real income

Topics:

Matias Vernengo considers the following as important: David Fields, Housing crisis, Urban crisis

This could be interesting, too:

Joel Eissenberg writes A housing crisis? Location, location, location

Matias Vernengo writes Soft landing or recession

Matias Vernengo writes Housing and Inequality in Utah

Matias Vernengo writes The Moral Economy of Housing

David Fields (Guest blogger)

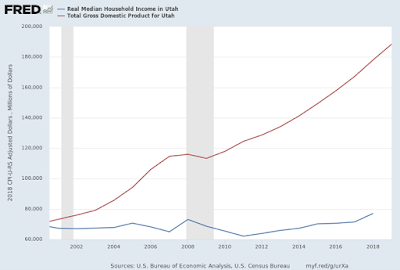

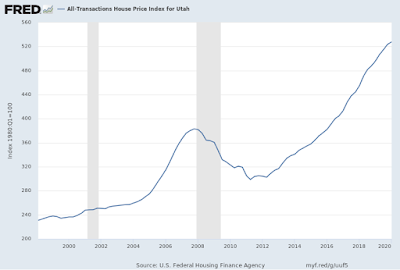

Rising housing costs and stagnating real wages are the primary causes of worsening housing affordability in Utah. The dismal wage growth is the result of a larger nationwide upward redistribution of wealth and income, which can be attributed to the following: a failure to adhere to full employment objectives; fiscal austerity; and various labor market policies and business practices allowing the higher social strata of a professional class to capture ever larger shares of economic growth. This is the result of institutional transformations that have exposed workers to the vulnerability of higher turnover, resulting in higher averages of unemployment, particularly worsened by the COVID-19 pandemic induced recession. For instance, from 2009 to 2016 real income only grew at 0.31% per year while rent crept upward at a rate of 1.03% per year in 2017 constant dollars. Slow and unequal wage growth stems from a growing wedge between overall productivity and the pay (wages and benefits) received by a typical worker.Housing market pressures drive up rents and home prices, making housing unaffordable and pushing long-time residents out of their communities, or into homelessness. Sometimes, these pressures result from targeted investments aimed at improving the quality of distressed neighborhoods. They can also result from gentrification, rapid growth in local jobs and population, or rising income inequality, all of which are not mutually exclusive. A countercyclical policy reaction to said pressures (solution 1) plays an essential role in moderating these market dynamics. Protecting against the displacement of long-time residents is vital; this also includes promoting spatial variation of affordable, i.e. mixed income, to prevent spatial inequality concerning the geographical segregation between “wealthy neighborhoods” “poorer neighborhoods.”

A stable and affordable home not only supports a household’s economic security and well-being, it can also help build wealth. Yet, many US households, particularly households of color, face steep barriers to buying a home or sustaining homeownership. Not only do people of color have lower homeownership rates than white people, they are less likely to sustain their homeownership. Black homeownership rates dropped significantly after the Great Recession to levels similar to those before the passage of the federal Fair Housing Act in 1968. Strict regulations against redlining, for example, can potentially expand stable housing and wealth-building opportunities to the nation’s increasingly diverse population.

- Ensuring Socially Equitable Affordable Housing Stays at Low Cost

- Protecting against Displacement

- Ensuring and Expanding Access to Secure Homeownership