Central planning (Socialism?) in democratic societies There is a lot being written on the causes and cures for the economic consequences of the Coronavirus (COVID-19). The predictable distinction is among those that think that this is essentially a demand shock, mostly to services, and those that are concerned with the disruption to supply chains. And to some extent both are correct. But that is not the more relevant problem here, which is whether we need just more government or a change in the nature of the governmental interventions.Neil Irwin, from the New York Times, provides a suitable and simple explanation of the demand shock story. Note that a demand shock often goes together with significant financial implications, as agents with reduced revenue tend to default on loans or

Topics:

Matias Vernengo considers the following as important: Dean Baker, Demand vs Supply Shocks, Galbraith, New Deal, Nikiforos, Planning, socialism, World War II

This could be interesting, too:

Bill Haskell writes Another False Social Security Emergency

Matias Vernengo writes Paul Davidson (1930-2024) and Post Keynesian Economics

Matias Vernengo writes More on the possibility and risks of a recession

Bill Haskell writes Dean Baker Editorializing on the Economy

There is a lot being written on the causes and cures for the economic consequences of the Coronavirus (COVID-19). The predictable distinction is among those that think that this is essentially a demand shock, mostly to services, and those that are concerned with the disruption to supply chains. And to some extent both are correct. But that is not the more relevant problem here, which is whether we need just more government or a change in the nature of the governmental interventions.

Neil Irwin, from the New York Times, provides a suitable and simple explanation of the demand shock story. Note that a demand shock often goes together with significant financial implications, as agents with reduced revenue tend to default on loans or payment streams to any liabilities. The Economist noted the risk associated with excessive corporate debt, and the possibility that the virus might trigger a debt-deflation type crisis in financial markets. On the fragility of corporate balance sheets see also this insightful piece by Michalis Nikiforos. Many economists have talked in favor of this interpretation, and certainly there is a lot to be said about this view, which I tend to agree with, by the way.

The fiscal expansion plans put forward by the administration have been mostly seen through the lens of a regular demand shock version of the recession. They include things like a bailout of certain sectors hit hard by the sudden decline in demand, like the airlines, and checks to those that have lost their jobs, besides the Fed injecting liquidity to reduce the financial effects of the demand shock. In that sense, not very different from the fiscal package and financial rescue of the 2008 crisis.

Of course, macroeconomic policies in 2008, even though they did preclude a fall in unemployment of the magnitude that had occurred in the 1930s during the Great Depression, were flawed in many ways. They did rescue banks, but left many to loose their houses for one (and Obama's Justice Department did not prosecute in any significant way the many financial excesses of Wall St); it was also probably on the smaller side, leading to a prolonged, but very slow, recovery, in which labor market conditions remained relatively poor for many workers, even with low levels of unemployment by the end. All things that increased the problems at the bottom of the income distribution and helped explain Trump's political victory in 2016. Hence, there is reasonable fear that these policies might not work well this time around again. Besides, there is a case to be made that this crisis is not fundamentally a demand shock.

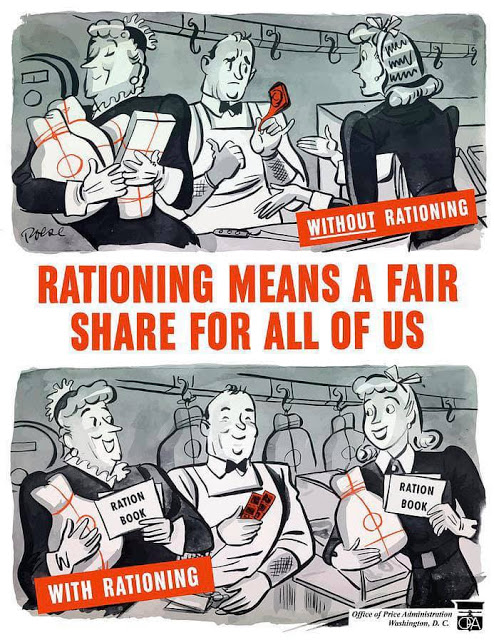

A prominent defender of the latter is Dean Baker. He says: "Our problem is not creating demand in the economy, the problem is keeping people more or less whole for a possibly extended period in which much of the economy is shut down." And as he notes, sending checks to people directly will fall short of a solution. Checks will be irrelevant for many, that have secure jobs, and insufficient for many, since it will be too little, or because some people might be directly excluded from such programs, like undocumented immigrants with US born children. Dean's alternative is to send money directly to companies that would keep workers employed and inactive, helping in the recovery too. Of course this solution deals fundamentally with those in the labor market, and not with those in more precarious situations.