The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of his employer. The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States will likely go down in history for any number of reasons. But let us leave this to one side for a moment and survey some of the collateral damage generated by the election. I am thinking of the pollsters. By all accounts these pollsters – specifically the pollster-cum-pundits – failed miserably in this election. Let us give some thought as to why – because it is a big question with large social and political ramifications. Some may say that the polls were simply wrong this election. There is an element of truth to this notion. The day of the election the RCP poll average put Clinton some three points ahead of Trump

Topics:

Philip Pilkington considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

The views expressed in this article are the author’s own and do not reflect the views of his employer.

The election of Donald Trump as president of the United States will likely go down in history for any number of reasons. But let us leave this to one side for a moment and survey some of the collateral damage generated by the election. I am thinking of the pollsters. By all accounts these pollsters – specifically the pollster-cum-pundits – failed miserably in this election. Let us give some thought as to why – because it is a big question with large social and political ramifications.

Some may say that the polls were simply wrong this election. There is an element of truth to this notion. The day of the election the RCP poll average put Clinton some three points ahead of Trump which certainly did not conform to the victory that Trump actually won. But I followed the polls throughout the election and did some analysis of my own and I do not think that this explanation goes deep enough.

I have a very different explanation of why the pollsters got it so wrong. My argument is based on two statements which I hope to convince you of:

- That the pollsters were not actually using anything resembling scientific methodology when investigating the polls. Rather they were simply tracking the trends and calibrating their commentary in line with them. Not only did this not give us a correct understanding of what was going on but it also gave us no real new information other than what the polls themselves were telling us. I call this the redundancy argument.

- That the pollsters were committing a massive logical fallacy in extracting probability estimates from the polls (and whatever else they threw into their witches’ brew models). In fact they were dealing with a singular event (the election) and singular events cannot be assigned probability estimates in any non-arbitrary sense. I call this the logical fallacy argument.

Let us turn to the redundancy argument first. In order to explore the redundancy argument I will lay out briefly the type of analysis that I did on the polls during the election. I can then contrast this with the type of analysis done by pollsters. As we will see, the type of analysis that I was advocating produced new information while the type of approach followed by the pollsters did not. While I do not claim that my analysis actually predicted the election, in retrospect it certainly helps explain the result – while, on the other hand, the pollsters failed miserably.

Why I (Sort Of) Called The Election

My scepticism of the US election polling and commentary this year was generated by my analysis of the polls during the run-up to the Brexit referendum. All the pollsters claimed that there was no way that Brexit could go through. I totally disagreed with this assessment because I noticed that the Remain campaign’s numbers remained relatively static while the Leave campaign’s numbers tended to drift around. What is more, when the Leave campaign’s poll numbers rose the number of undecided voters fell. This suggested to me that all of those that were going to vote Remain had decided early on and the voters that decided later and closer to the election date were going to vote Leave. My analysis bore out in the election but I did not keep any solid, time-stamped proof that I had done such an analysis. So when the US election started not only did I want to see if a similar dynamic could be detected but I wanted to record its discovery in real time.

When I examined the polls I could not find the same phenomenon. But I then realised that (a) it was too far away from the election day and (b) this was a very different type of election than the Brexit vote and because of this the polls were more volatile. The reason for (b) is because the Brexit vote was not about candidates so there could be no scandal. When people thought about Brexit they were swung either way based on the issue and the arguments. If one of the proponents of Brexit had engaged in some scandal it would be irrelevant to their decision. But in the US election a scandal could cause swings in the polls. Realising this I knew that I would not get a straight-forward ‘drift’ in the polls and I decided that another technique would be needed.

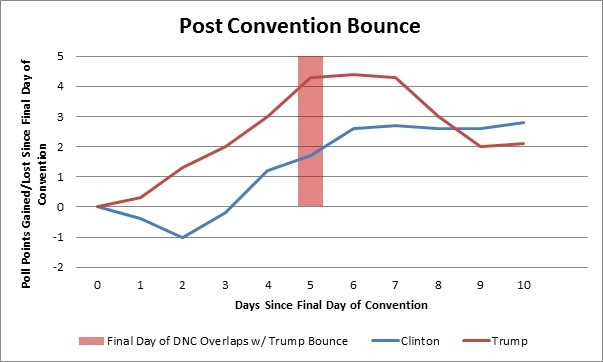

Then along came the Republican and Democratic conventions in July. These were a godsend. They allowed for a massive experiment. That experiment can be summarised as a hypothesis that could be tested. The hypothesis was as follows: assume that there are large numbers of people who take very little interest in the election until it completely dominates the television and assume that these same people will ultimately carry the election but they will not make up their minds until election day; now assume that these same people will briefly catch a glimpse of the candidates during the conventions due to the press coverage. If this hypothesis proved true then any bounce that we saw in the polls during the conventions should give us an indication of where these undecided voters would go on polling day. I could then measure the relative sizes of the bounces and infer what these voters might do on election day. Here are those bounces in a chart that I put together at the time:

Obviously Trump’s bounce was far larger than Clinton’s. While it may appear that Clinton’s lasted longer this is only because the Democratic convention was on five days after the Republican convention so it stole the limelight from Trump and focused it on Clinton. This led to his bump falling prematurely. It is clear that the Trump bounce was much more significant. This led me to believe that undecided voters would be far more likely to vote Trump than Clinton on election day – and it seems that I was correct.

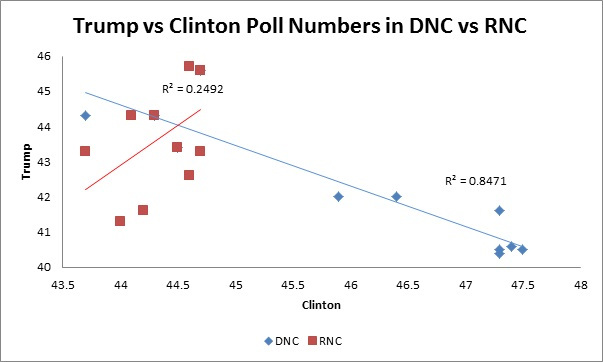

In addition to this it appeared that Trump was pulling in undecideds while Clinton had to pull votes away from Trump. We can see this in the scatterplot below.

What this shows is that during the Republican National Convention (RNC) Trump’s support rose without much impacting Clinton’s support – if we examine it closely it even seems that Clinton’s poll numbers went up during this period. This tells us that Trump was pulling in new voters that had either not decided or had until now supported a third party candidate. The story for Clinton was very different. During the Democratic National Convention (DNC) Clinton’s support rose at the same time as Trump’s support fell. This suggests that Clinton had to pull voters away from Trump in order to buttress her polls numbers. I reasoned that it was far more difficult to try to convince voters that liked the other guy to join your side than it is to convince enthusiastic new voters. You had to fight for these swing voters and convince them not to support the other guy. But the new voters seemed to be attracted to Trump simply by hearing his message. That looked to me like advantage Trump.

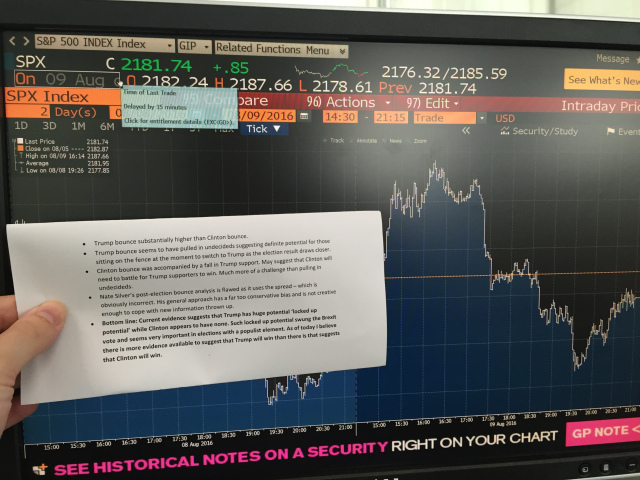

“Aha!” you might think, “maybe you’re just faking it. How do I know that you didn’t just create that chart after the election?” Well, this is why I time-stamped my results this time around. Here are the results of my findings summarised on a piece of paper next to a Bloomberg terminal on August 9th.

I also sent this analysis to some of the editors that are handling this piece. So they have this analysis in their email archives and can check to see that I’m not just making this up.

The reader may note that I criticise Nate Silver’s analysis in the text in the picture. I was referring to his post-convention bounce analysis in which he used the spread between the two candidates to gauge it – this was an incorrect methodology because as we have already seen the Democratic convention ate away at the Trump bounce because it came during the Trump bounce and this artificially inflated Clinton’s bounce in spread terms. The correct methodology was to consider the two bounces independently of one another while keeping in mind that the DNC stole the limelight from Trump five days after his bounce started and thereby brought that bounce to a premature halt.

This was a bad analytical error on Silver’s part but it is not actually what really damaged his analysis. What damaged his analysis significantly is that he did not pay more attention to this ‘natural experiment’ that was thrown up by the convention. Rather he went back to using his tweaked average-tracking polls. This meant that while he was following trends I was looking for natural experiments that generated additional information to that which I had from the polls. This led to Silver and other pollsters becoming trapped in the polls. That is, they provided no real additional information than that contained in the polls.

After this little experiment, as the polls wound this way and that based on whatever was in the news cycle I constantly fell back on my analysis. What was so fascinating to me was that because the pollsters simply tracked this news cycle through their models their estimates were pretty meaningless. All they were seeing was the surface phenomenon of a tumultuous and scandal-ridden race. But my little experiment had allowed me a glimpse into the heart of the voter who would only make up their mind on voting day – and they seemed to favour Trump.

Before I move on, some becoming modesty is necessary: I do not believe that I actually predicted the outcome of the election. I do not think that anyone can predict the outcome of any election in any manner that guarantees scientific precision or certainty (unless they rigged it themselves!). But what I believe I have shown is that if we can detect natural experiments in the polls we can extract new information from those polls. And what I also believe I have shown is that the pollsters do not generally do this. They just track the polls. And if they just track the polls then instead of listening to them you can simply track the polls yourself as the pollsters give you no new information. In informational terms pollsters are… simply redundant. That is the redundancy argument.

Why the Pollsters’ Estimates Are So Misleading

Note the fact that while my little experiment gave me some confidence that I had some insight into the minds of the undecided voter – more than the other guy, anyway – I did not express this in probabilistic terms. I did not say: “Well, given the polls are at x and given the results of my experiment then the chance of a Trump victory must be y”. I did not do this because it is impossible. Yet despite the fact that it is impossible the pollsters do indeed give such probabilities – and this is where I think that they are being utterly misleading.

Probability theory requires that in order for a probability to be assigned an event must be repeated over and over again – ideally as many times as possible. Let’s say that I hand you a coin. You have no idea whether the coin is balanced or not and so you do not know the probability that it will turn up heads. In order to discover whether the coin is balanced or skewed you have to toss it a bunch of times. Let’s say that you toss it 1000 times and find that 900 times it turns up heads. Well, now you can be fairly confident that the coin is skewed towards heads. So if I now ask you what the probability of the coin turning up heads on the next flip you can tell me with some confidence that it is 9 out of 10 (900/1000) or 90%.

Elections are not like this because they only happen once. Yes, there are multiple elections every year and there are many years but these are all unique events. Every election is completely unique and cannot be compared to another – at least, not in the mathematical space of probabilities. If we wanted to assign a real mathematical probability to the 2016 election we would have to run the election over and over again – maybe 1000 times – in different parallel universes. We could then assign a probability that Trump would win based on these other universes. This is silly stuff, of course, and so it is best left alone.

So where do the pollsters get their probability estimates? Do they have access to an interdimensional gateway? Of course they do not. Rather what they are doing is taking the polls, plugging them into models and generating numbers. But these numbers are not probabilities. They cannot be. They are simply model outputs representing a certain interpretation of the polls. Boil it right down and they are just the poll numbers themselves recast as a fake probability estimate. Think of it this way: do the odds on a horse at a horse race tell you the probability that this horse will win? Of course not! They simply tell you what people think will happen in the upcoming race. No one knows the actual odds that the horse will win. That is what makes gambling fun. Polls are not quite the same – they try to give you a snap shot of what people are thinking about how they will vote in the election at any given point in time – but the two are more similar than not. I personally think that this tendency for pollsters to give fake probability estimates is enormously misleading and the practice should be stopped immediately. It is pretty much equivalent to someone standing outside a betting shop and, having converted all the odds on the board into fake probabilities, telling you that he can tell you the likelihood of each horse winning the race.

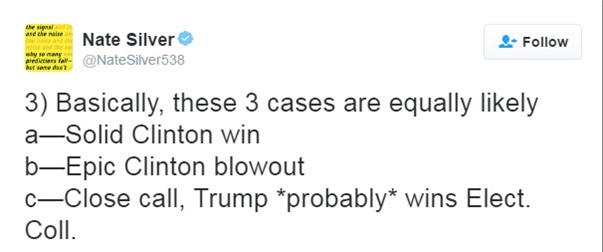

There are other probability tricks that I noticed these pollsters doing too. Take this tweet from Nate Silver the day before the election. (I don’t mean to pick on Silver; he’s actually one of the better analysts but he gives me the best material precisely because of this).

Now this is really interesting. Ask yourself: Which scenarios are missing from this? Simple:

- Epic Trump blowout

- Solid Trump win

Note that I am taking (c) to mean that if the election is close or tied Silver can claim victory due to his statement of ‘*probably*’.

Now check this out. We can actually assign these various outcomes probabilities using the principle of indifference. What we do is we simply assign them equal probabilities. That means each has a 20% chance of winning. Do you see something awry here? You should. Silver has really covered his bases, hasn’t he? Applying the principle of indifference we can see that Silver has marked out 3 of the 5 possible scenarios. That means that even if we have no other information we can say that Silver has a 60% chance of ‘predicting the election’ using this statement. Not bad odds!

What is more, we can actually add in some fairly uncontroversial information. When this tweet was sent out the polls showed the candidates neck-and-neck. Surely this meant that a simple reading of the polls would tell us that it was likely to be a close call. Well, I don’t think it would be unfair to then weight the probability of (c) accordingly. Let’s say that the chance of a close call, based on the polls, was 50%. The rest of the possibilities then get assigned the rest of the probability equally – they get 12.5% each. Now Silver really has his bases covered. Without any other information he has a 75% chance of calling the election based on pure chance.

The irony is, of course, he got unlucky. Yes, I mean ‘unlucky’. He rolled the dice and the wrong number came up. Though he lost the popular vote, Trump won the electoral votes needed by a comfortable margin. But that is not the key point here. The key point here is that something else entirely is going on in this election forecasting business than what many people think is happening. What really appears to be going on is that (i) pundits are converting polls numbers into fake probability estimates arbitrarily and (ii) these same pundits are making predictive statements that are heavily weighted to being ‘probably’ correct – even if they are not conscious that they are doing this. This is really not much better than reading goat entrails or cold reading. Personally, I am more impressed by a good cold reader. The whole thing is based on probabilistic jiggery-pokery. That is the logical fallacy argument.

And Why You Should Listen to Neither of Us

Are you convinced? I hope so – because then you are being rational. But what is my point? My very general point is that we are bamboozling ourselves with numbers. Polls are polls. They say what they say. Sometimes they prove prescient; sometimes they do not. If we are thoughtful we can extract more information by analysing these polls carefully, as I did with my little experiment. But beyond this we can do little. Polls do not predict the future – they are simply a piece of information, a data point – and they cannot be turned into probability estimates. They are just polls. And they will always be ‘just polls’ no matter what we tell ourselves.

But beyond this we should stop fetishizing this idea that we can predict the future. It is a powerful and intoxicating myth – but it is a dangerous one. Today we laugh at the obsession of many Christian Churches with magic and witchcraft but actually what these institutions were counselling against is precisely this type of otherworldly prediction:

The Catechism of the Catholic Church in discussing the first commandment repeats the condemnation of divination: “All forms of divination are to be rejected: recourse to Satan or demons, conjuring up the dead or other practices falsely supposed to ‘unveil’ the future. Consulting horoscopes, astrology, palm reading, interpretation of omens and lots, the phenomena of clairvoyance, and recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power over time, history, and, in the last analysis, other human beings, as well as a wish to conciliate hidden powers. These practices are generally considered mortal sins.

Of course I am not here to convert the reader to the Catholic Church. I am just making the point that many institutions in the past have seen the folly in trying to predict the future and have warned people against it. Today all we need say is that it is rather silly. Although we would also not go far wrong by saying, with the Church, that “recourse to mediums all conceal a desire for power over time, history, and, in the last analysis, other human beings”. That is a perfectly good secular lesson.

I would go further still. The cult of prediction plays into another cult: the cult of supposedly detached technocratic elitism. I refer here, for example, to the cult of mainstream economics with their ever mysterious ‘models’. This sort of enterprise is part and parcel of the cult of divination that we have fallen prey to but I will not digress too much on it here as it is the subject of a book that I will be publishing in mid-December 2016 – an overview of which can be found here. What knowledge-seeking people should be pursuing are tools of analysis that can help them better understand the world around us – and maybe even improve it – not goat entrails in which we can read future events. We live in tumultuous times; now is not the time to be worshipping false idols.