A slightly edited version of this article first appeared in the Economic and Political Weekly on 22 July 2023. Summary: This article is the third and last in a series of articles on monetary policy debates in the age in which deglobalisation became a buzzword. Here, we continue our discussion of the ongoing Turkish monetary policy experiment by focusing on macroprudential measures, capital controls and central bank independence, as promised in the first article, as an example of these debates. Introduction In the second article of this series, “The Turkish Experiment—II,” we went back to 1980 and summarised what happened along the way to the ongoing monetary experiment that started after the currency crisis of August 2018. Now, we shift our focus to central banking in Turkey and briefly

Topics:

Hasan Cömert & T. Sabri Öncü considers the following as important: Article, Finance & Regulation, International & World, Long Read, Monetary Policy

This could be interesting, too:

Jeremy Smith writes UK workers’ pay over 6 years – just about keeping up with inflation (but one sector does much better…)

T. Sabri Öncü writes Argentina’s Economic Shock Therapy: Assessing the Impact of Milei’s Austerity Policies and the Road Ahead

T. Sabri Öncü writes The Poverty of Neo-liberal Economics: Lessons from Türkiye’s ‘Unorthodox’ Central Banking Experiment

Matias Vernengo writes Very brief note on the Brazilian real and the fiscal package

A slightly edited version of this article first appeared in the Economic and Political Weekly on 22 July 2023.

Summary: This article is the third and last in a series of articles on monetary policy debates in the age in which deglobalisation became a buzzword. Here, we continue our discussion of the ongoing Turkish monetary policy experiment by focusing on macroprudential measures, capital controls and central bank independence, as promised in the first article, as an example of these debates.

Introduction

In the second article of this series, “The Turkish Experiment—II,” we went back to 1980 and summarised what happened along the way to the ongoing monetary experiment that started after the currency crisis of August 2018. Now, we shift our focus to central banking in Turkey and briefly analyse how it evolved under the ongoing 20-years’ reign of the Justice and Development Party (AKP), the governing political party in Turkey, from November 2002 to April 2016.

In April 2016, Murat Çetinkaya assumed the position of chair, leading the central bank until he was dismissed in July 2019. It was during his tenure that the currency crisis of August 2018 took place. We then analyse the ongoing monetary experiment that started in his term in detail. This is preceded by the ongoing monetary policy debates in the age in which deglobalisation became a buzzword.

Monetary Policy Debates

Although the monetary policy debates on central bank independence, macroprudential measures and capital controls have intensified after the Global Financial Crisis (GFC) of 2007-2008 (Haldane 2021), each can be traced back to decades earlier.

The world’s first legally independent central bank is probably the central bank of the United States (US), the Federal Reserve (Fed). The Fed gained its independence from the Treasury with the Treasury-Fed Accord of 4 March 1951 (Hetzel and Leach 2001). However, the widespread adoption of central bank independence was born out of the Great Inflation of the 1970s (Haldane, 2021), and its academic roots go back to the seminal articles by Kydland and Prescott (1977) and Barro and Gordon (1983). They argued that policymakers should follow rules rather than have discretion because discretion would result in time inconsistent outcomes as politicians may seek short-term political gains.

Then, central bank independence became the mantra in the 1980s, and by the end of the 20th Century, about 80-90% of the world’s central banks were independent, at least operationally (Haldane, 2021). Pioneered by the Reserve Bank of New Zealand in 1989, the inflation targeting became the game in town, and the independent central banks focused on price stability (that is, low inflation) by employing a single tool, namely, a short-term interest rate, usually overnight.

Not that no one had questioned central bank independence, inflation targeting, a single monetary policy tool consisting of a short-term interest rate, and the single objective of price stability before the GFC (see, for example, Forder, 1998 and the references therein). However, the GFC changed all that. In response to the GFC, central banking practices underwent significant changes in both developed and developing countries. The obsession with single-digit inflation targeting weakened, and concerns about financial stability and macroprudential measures gained importance (Benlialper and Cömert 2015).

While the term “macroprudential” gained popularity following the GFC, its precise meaning remained ambiguous (Clement, 2010). Clement (2010) traced the term’s origins to a subsection titled “The ‘macro-prudential’ risks inherent in maturity transformation in banks’ international business” in a Bank of International Settlements (BIS) report (BS/79/44, dated November 1979). The use of quotation marks in the title indicated to him that the term was regarded as somewhat new or novel.

What was referred to as “macroprudential risk” in that report is now commonly known as systemic risk, which can be broadly defined as the expected losses resulting from the failure of a significant portion of the financial sector, leading to a reduction in credit availability and potential adverse effects on the real economy (Acharya and Öncü, 2012). The European Central Bank (ECB) defines macroprudential measures as those aimed at enhancing the financial system’s resilience to identified systemic risks (ECB, 2023), a definition broad enough to encompass a multitude of measures, potentially leading to a wide range of approaches being called macroprudential. So the ambiguity Clement identified remains true to this day.

We discussed the liberalisation of capital accounts that started in the 1980s in the previous articles of the series (Öncü and Öncü, 2022 and Cömert and Öncü, 2023a). This liberalisation resulted in the removal of capital controls in most countries, developed and developing, alike. According to Trilemma, one of the cornerstones of international finance theory and monetary economics, under a fixed exchange rate regime, the determination of domestic interest rates independently from world interest rates is only possible with capital controls. In other words, the effectiveness of monetary policy can only be achieved by either abandoning capital mobility or giving up the fixed exchange rate regime. Here, by effectiveness, we refer to the ability to reach the stated goals.

Although many unorthodox economists, such as Palley (2003), Grabel (2003), and Vernango (2006), focused on the adverse effects of capital flows in developing countries to argue that even under floating exchange rate regimes, developing countries would have limited monetary policy manoeuvrability without capital controls even before the GFC, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) took action only after the GFC. In a 2012 policy paper titled “The Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows: An Institutional View”, the IMF claimed that although capital flows are desirable because they can bring substantial benefits to recipient countries, they can also result in macroeconomic challenges and financial stability risks (IMF 2012). The policy paper hesitantly proposed the inclusion of capital flow management measures (CFMs), macroprudential measures (MPMs), and CFMs that are also MPMs (CFM/MPMs) into the policy toolkit, albeit in a limited manner (during inflow surges and disruptive outflows), and outlined the circumstances in which they might be useful. However, it stressed that these measures should not be seen as a substitute for necessary macroeconomic adjustments (IMF, n.d.).

Shortly after the publication of the IMF’s institutional view, Hélène Rey (2013) presented an article titled “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence” at the Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve of Kansas City Economic Symposium in August 2013. In her article, Rey argued that whenever capital is freely mobile, the global financial cycle constrains national monetary policies regardless of the exchange rate regime and that the global financial cycle has transformed the well-known Trilemma into a ‘Dilemma’.

Cömert (2016, 2019), following an evolutionary / institutional / structural framework, and partly inspired by Rey (2013), has argued that developments since the 1980s have progressively reduced central banks’ capacity to implement effective monetary policies, resulting in the progressive transformation of post-Bretton Woods central banking from Trilemma to Dilemma. In contrast to Rey, Cömert (2013, 2016, 2019) also emphasizes the role of central banks’ policy choices and changes in local markets as factors influencing the effectiveness of national monetary policy.

Scholarship on the Dilemma rightly argues that financial flows can significantly influence the macro variables of developing countries through various channels. However, as demonstrated by the example of Turkey, even in the absence of capital outflows, a sudden increase in domestic investors’ demand for foreign currencies and precious metals such as gold, resulting from flight to safety (see, for example, Cömert and Öncü, 2023b), constantly threatens the effectiveness of central bank policies in developing countries. With this understanding, let us now focus on the Turkish example.[1]

Monetary Policy before Çetinkaya

The Central Bank of the Republic of Turkey (CBRT) conducts its monetary policy not only through open market operations but also occasionally utilises “lender of last resort” operations in its monetary policy implementation, although it stopped using the latter since 1 June 2018. The foundation of the open market operations infrastructure was established with the initiation of Government Domestic Debt Securities (GDDS) auctions on 29 May 1985. After launching the interbank money market within its own structure on 2 April 1986, the CBRT started conducting open market operations on 4 February 1987.

Initially, the CBRT relied on the following three main tools:

- Direct purchases and sales;

- Sale and repurchase agreements (repos) and purchase and resale agreements (reverse repos);

- Required reserve ratios for deposits.

As discussed in the second article of the series, the partial trade liberalization in 1984 allowed for holding foreign currency (FX) accounts at domestic banks. This was facilitated through Decree No. 30 on the Protection of the Value of Turkish Currency, issued on 7 July 1984. With a significant increase in FX deposits following the implementation of Decree No. 30, starting from 1 January 1986, the CBRT extended the reserve requirements to cover FX deposits in addition to Turkish lira (TRY) deposits, which had been subject to reserve requirements since the CBRT’s establishment on 30 May 1933.

These initial tools were later complemented by additional tools as the CBRT’s open market operations evolved. On 5 July 1999, the CBRT introduced the intraday liquidity facility (IDLF) as the first lender of last resort facility to address urgent funding needs in the banking system and alleviate congestion in payment systems.

When the 2001 crisis arrived shortly after, it had significant effects on central banking in Turkey. On the night of 21 February 2001, a decision was made to transition from a crawling-pegged to a flexible exchange rate regime, following the outbreak of the currency crisis. Furthermore, starting from 29 March 2001, the CBRT initiated FX purchase and sale auctions to support banks in meeting their short-term foreign exchange liabilities. As part of the IMF-supported structural reform program, the direct financing of the government by the CBRT was prohibited, and in April 2001, the bank achieved instrument independence.

On 28 March 2002, the CBRT introduced another innovation by adding deposit purchase and sale instruments, known as depos, to repos and reverse repos. Additionally, from 1 July 2002, the CBRT implemented the Late Liquidity Window (LLW/LON) [2] as an overnight depo facility, operating within the framework of its function as the lender of last resort. Repos and depos are essentially collateralized borrowing and lending instruments [3], and apart from certain legal details, accepted collaterals, and usage, they do not have significant operational differences. The significance of depos was that they broadened the set of acceptable collaterals beyond GDDS, which were the only acceptable collaterals for repos. This expansion aimed to address the increasing funding needs of banks during the banking crisis erupted on 19 February 2001.

During the period from 2002 to 2005, the CBRT, in collaboration with the government, embraced an implicit inflation targeting (IT) policy. This policy involved setting inflation targets and maintaining instrument independence to attain those targets. After some minor changes in 2006, the implicit IT regime took an explicit form of announcing inflation targets for the next three years and determining the overnight interest rate in monthly Monetary Policy Committee meetings. Similar to other IT practices, the CBRT relied on overnight interest rates and a commitment to a flexible exchange rate regime as fundamental components of this policy framework.

Within this framework, the CBRT began implementing an interest rate corridor in a narrow band. The corridor consisted of the lower bound represented by the overnight reverse repo borrowing rate and the upper bound represented by the overnight repo lending rate. Effectively, the lower bound became the policy rate.

During the implementation of the IT regime under the supervision of the IMF, significant reforms were implemented in the financial sector. Additionally, new independent regulatory bodies, including the Banking Regulation and Supervision Authority (BRSA), were established.

Further, through a regulation published in the Official Gazette on 5 October 2006, the legal framework for issuing and redeeming Liquidity Securities was established. However, except for four issuances made between 19 July 2007, and 15 November 2007, the CBRT did not utilise this instrument.

At that time, due to the substantial liquidity generated through the bank rescue operations guided by the IMF following the 2001 banking crisis, and the purchase of foreign currency as capital flows redirected inward in 2002 due to monetary expansion in the US, Europe and other advanced economies, the CBRT was a net borrower. To manage the excess liquidity, Liquidity Securities were introduced as additional instruments to withdraw liquidity.

However, the onset of the GFC and the subsequent reversal in capital flows reduced the necessity for their utilisation. Indeed, with the substantial increase in the size and volatility of capital flows into developing economies following the GFC, the CBRT transitioned into a net lender position starting from 2010, which it continues to maintain to this day. Consequently, the overnight reverse repo borrowing rate, which served as the lower bound of the corridor, lost its effectiveness as the policy rate.

Following that, on 18 May 2010, the CBRT introduced one-week term repo quantity auctions using the quotation method and adopted the interest rate of one-week term repos as the policy rate. Subsequently, on 18 September 2010, the CBRT transitioned to a wide interest rate corridor encompassing the previous lower and upper bounds, with the new policy rate positioned somewhere in the middle. The core concept of this framework involved asymmetrically setting the width of the interest rate corridor around the policy rate to attain a desired weighted average funding rate. This was achieved by actively managing funding through one-week repo and overnight repo facilities. This rate is called the CBRT weighted average funding rate.

The reserve option mechanism (ROM) invented by the CBRT was the last monetary policy tool inherited by Çetinkaya from his predecessors. While the CBRT referred to it as a monetary policy tool, it can also be regarded as a macroprudential measure, as it was designed to enhance the economy’s resilience against the volatility of capital flows and external financial shocks (Aslaner et al., 2015). Effective 16 September 2011, the ROM was introduced through an amendment to the Regulation on Required Reserves, which was published in the Official Gazette on 12 September 2011. The ROM gave the banks the option to hold a fraction of their required reserves for TRY liabilities in US dollar (USD), euro, and standard gold and, on 4 November 2016, the option of maintaining required reserves also with scrap gold was added to the mechanism.

The assumption was that banks would react to the volatility in capital flows by adjusting their ROM utilisation so that it would act as an automatic stabiliser to smooth the impact of capital flows on the domestic economy. Unfortunately, history has shown that the ROM has not behaved as expected during capital outflows: rather than decreasing their ROM utilisation, banks did the opposite (see, for example, Aslaner et al., 2015).

The tool diversification we have summarised above was a natural consequence of the CBRT adding financial stability (and growth) as an objective to its price stability goal, in line with similar examples worldwide. The CBRT had no choice but to diversify its monetary policy tools to cope with the increased volatility in financial flows caused by the monetary expansion policies associated with the GFC, such as the Quantitative Easing (QE) policy of the Fed, in developed countries. Although the CBRT planned to return to the inflation targeting regime after 2010, it has not been able to realise this transition until today.

Monetary Policy from Çetinkaya to Kavcıoğlu

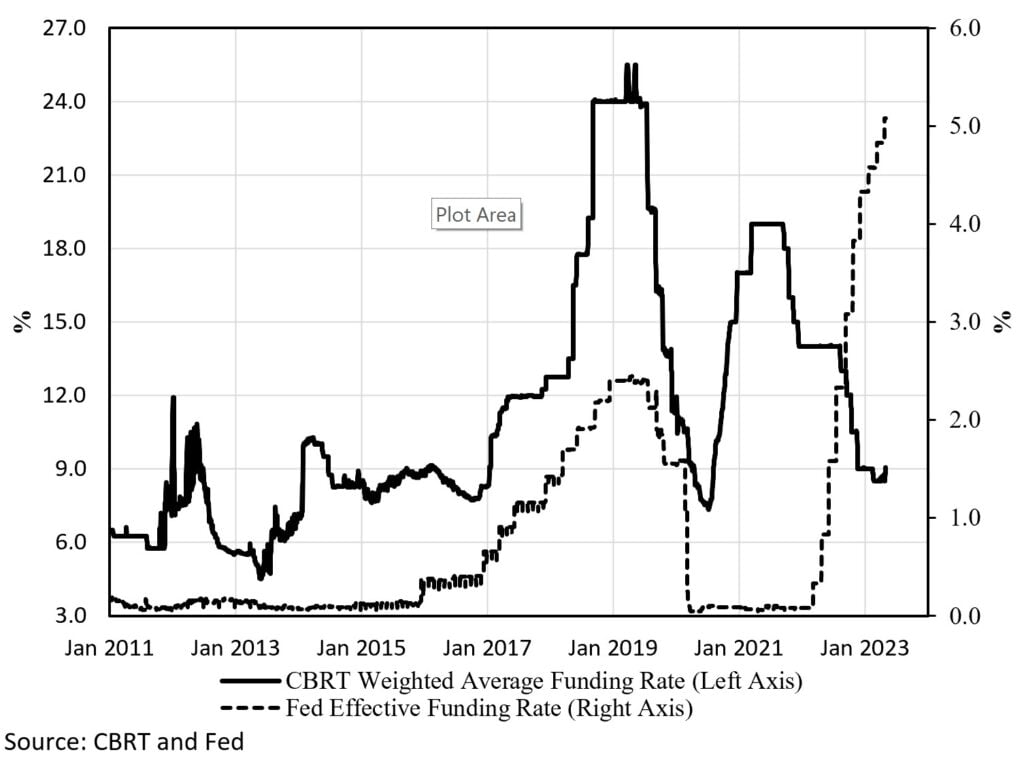

The AKP and its leader Recep Tayyip Erdoğan adopted a policy of reducing interest rates from the early days of their rule. This stance resulted in tensions between President Erdoğan and the CBRT chairs, except for Şahap Kavcıoğlu, who served as the CBRT Chair from 20 March 2021 to 9 June 2023. Çetinkaya was no exception. The reason why Kavcıoğlu did not have any conflicts with President Erdoğan should be evident from Figure 1, which illustrates the CBRT weighted average funding rate in comparison to the Fed effective funding rate.

While all the other CBRT chairs responded and aligned with the monetary policy decisions of the Fed, including its decisions on its QE program, which are not shown in the figure, Kavcıoğlu was the only CBRT chair who consistently lowered the CBRT policy rate even as the Fed was raising theirs. How Kavcıoğlu was able to accomplish this is part and parcel of the monetary policy experiment that has been ongoing since the August 2018 currency crisis.

Figure 1: CBRT Weighted Average and Fed Effective Funding Rates (Daily Data)

We should mention also that a year after Çetinkaya became the chair of the CBRT on 19 April 2016, with the 16 April 2017 referendum, Turkey transitioned from a parliamentarian regime to a presidential regime. Then, Erdoğan won the presidency in the presidential and general elections on 25 June 2018, and gave himself the legal right to appoint and dismiss a long list of high ranking civil servants including the high ranking officers of the CBRT.

It is difficult to describe Çetinkaya’s tenure as the chair of the CBRT as fortunate. In addition to the referendum and general elections mentioned above, the March 2019 local elections took place during his tenure, all of which resulted in significant pressure from Erdoğan to lower rates in order to ensure high economic growth and low unemployment. In the meantime, the Fed continued raising its own interest rate corridor by 25 basis points that it started on 16 December 2015 from 0-0.25% to reach 2.25-2.50% by 20 December 2018 through a series of nine moves, and initiated its quantitative tightening in October 2017, which continued until 31 July 2019 when it was brought to an end due to the repo mini-crisis that occurred in the US in the summer of 2019.

In the absence of capital controls, with the ensuing capital outflows, Çetinkaya had no choice but to respond to the Fed. And so he did, as can be seen in Figure 1. However, he did it in a convoluted way to partially satisfy Erdoğan. Shortly after the beginning of Çetinkaya’s tenure, on 3 August 2016, the CBRT added the Late Liquidity Window Repo (LLW Repo) facility to its lender of last resort facilities. Although debates on simplifying the wide interest rate corridor introduced in 2010 started in 2015 in earnest because of communication problems it created, and Çetinkaya was in favour of simplification, he further complicated it, at least at first glance.

On 16 January 2017, the CBRT initiated funding through the LLW Repo facility, which had an interest rate higher than the overnight repo lending rate and served as the fourth rate in the expanded wide interest rate corridor. This move seems to be an effort to meet Erdoğan’s expectations regarding interest rates, as it enabled the CBRT to align with the Fed’s interest rate hikes through its weighted average funding rate. By shifting most of the funding to the LLW Repo facility, the CBRT avoided raising the official policy rate, the one-week repo rate.

This continued until the Fed initiated its quantitative tightening in October 2017. Subsequently, on 22 November 2017, the CBRT transitioned to conducting all its funding operations through the LLW Repo, a practice that remained in effect until 31 May 2018. Through this approach, the CBRT effectively transformed the LLW Repo lending rate into the policy rate without explicit acknowledgment, simplifying the wide interest rate corridor. As depicted in Figure 1, it increased the weighted average funding rate from 8.74% on 16 January 2017 to 16.50% on 24 May 2018.

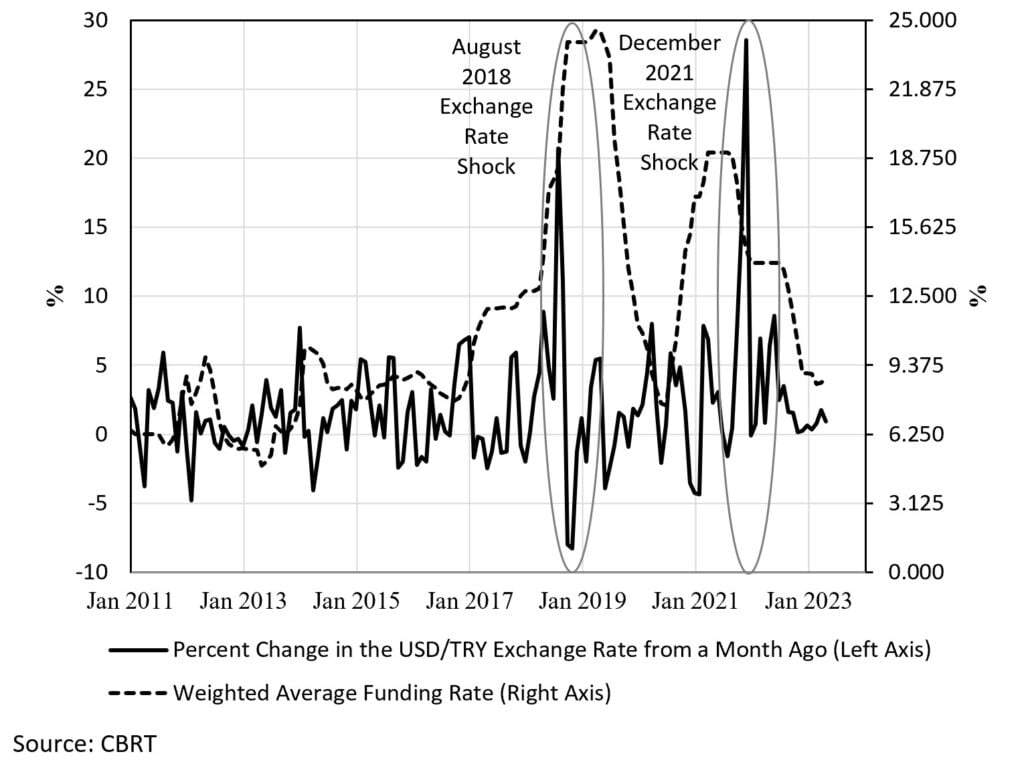

Of course, this did not go unnoticed. In response to criticisms regarding the clarity, predictability, and effectiveness of its monetary policy implementation, the CBRT announced the formalization of the simplification on 28 May 2018 through a press release. As of 1 June 2018, the CBRT switched to a symmetric narrow corridor of width 300 basis points, with the original lower and upper bounds, and the official policy rate, the one-week repo lending rate, in the middle. The CBRT set the official policy rate to 16.50%. Shortly after, a crisis between Turkey and the US flared up over an American pastor imprisoned in Turkey since 2016. On 9 August 2018, the then US President Trump announced economic sanctions on Turkey, leading to the exchange rate shock illustrated in Figure 2: a 28% surge in the USD/TRY exchange rate from 9 August to 14 August.

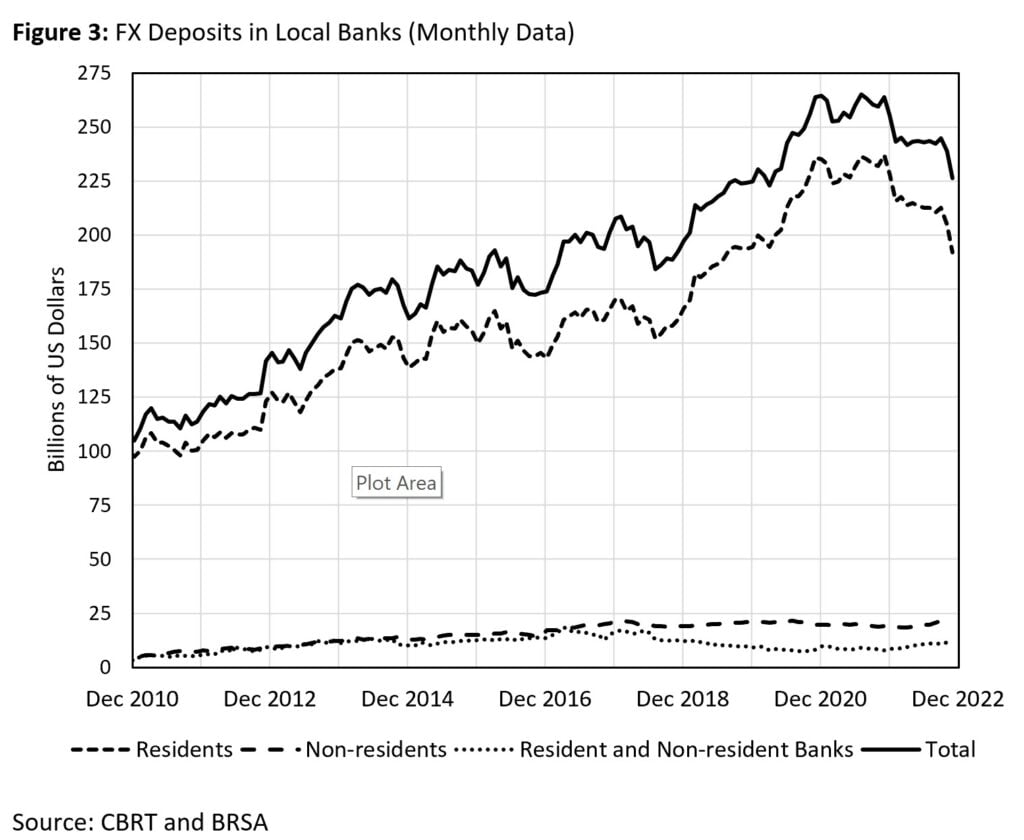

In response to the exchange rate shock, the CBRT raised the policy rate from 17.75% on 9 August 2018 to 19.25% on 17 August 2018. However, primarily due to persistent capital outflows by both non-residents and residents, and initially to a lesser extent, a transition of residents from TRY deposit accounts to FX deposit accounts in local banks (deposit dollarisation), about a month later, on 14 September 2018, the rate was further increased to 24% in order to stabilize the exchange rate (see Figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2: Percent Change in the USD/TRY Exchange Rate from a Month Ago and the CBRT Weighted Average Funding Rate (Monthly Data)

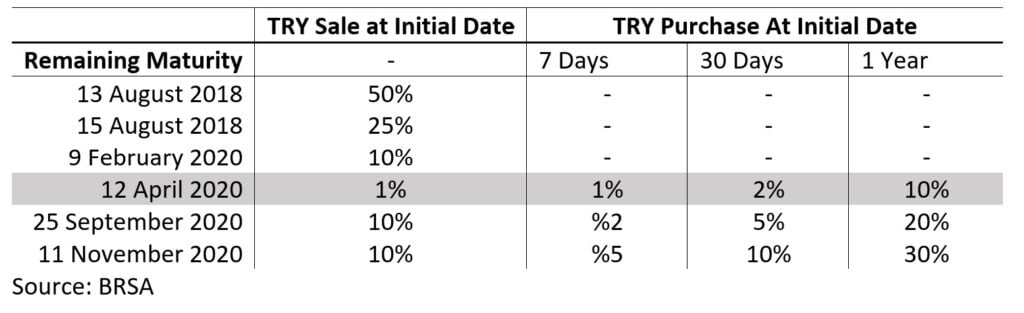

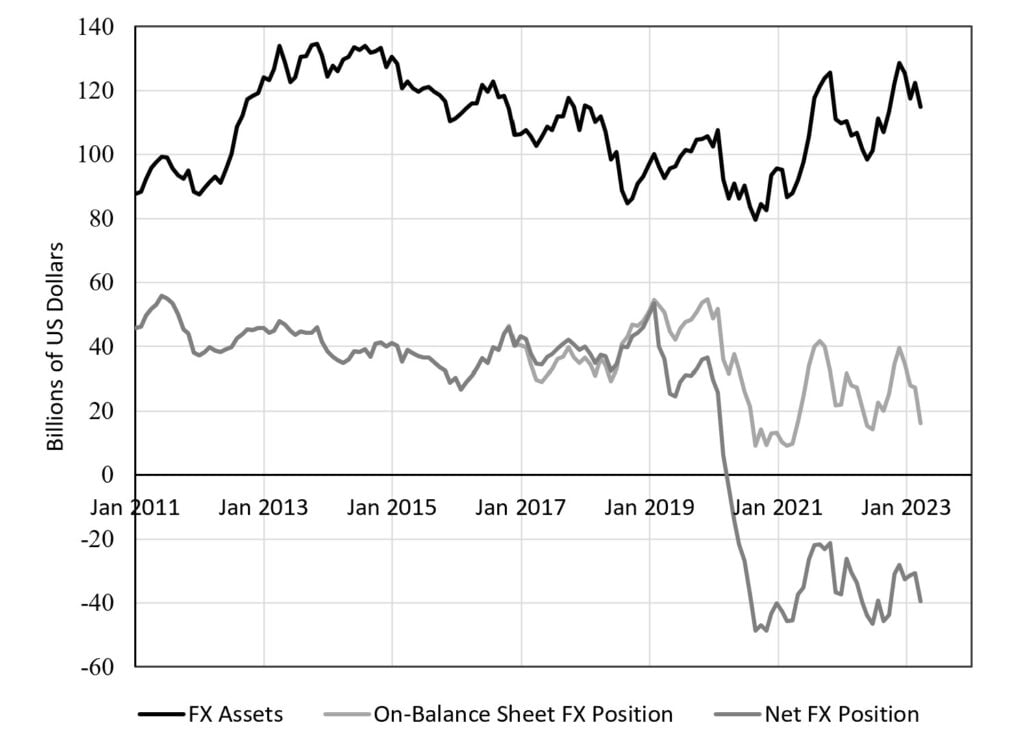

A significant event that occurred at the peak of the August 2018 currency crisis was the announcement of a derivatives transaction restriction on domestic banks by the BRSA on 13 August 2018, which the BRSA [Turkey’s Banking Regulation and Supervision Agency – ed] called a macroprudential measure. On that day, the BRSA announced that the total notional principal amount of banks’ currency swaps and other similar products (spot + forward FX transactions) with foreign counterparties, where local banks pay TRY and receive FX at the initial date, should not exceed 50% of the bank’s most recent regulatory capital. Two days later, the BRSA reduced this percentage to 25%.

While the BRSA did not provide an explicit explanation for the measure, it is evident that it limits the amount of TRY that non-resident speculators could borrow for short-selling, thus reducing exchange rate volatility. Therefore, this measure can be categorized as both a macroprudential measure (MPM) and a capital flow management measure (CFM) according to the taxonomy of the IMF (n.d.). Whether this measure should be labelled CFM/MPM or MPM/CFM in the IMF’s taxonomy is, of course, a subject of debate. Let us call it the BRSA swap measure. After the onset of the Covid-19 pandemic and the accompanying financial instability in early 2020, the BRSA swap measure was broadened and tightened to become even more restrictive to the extent that it effectively shut down the offshore TRY currency swap market. Table 1 illustrates the evolution of the measure over time.

Given that President Erdoğan’s expectations from Çetinkaya were to maintain control over the exchange rate and avoid raising interest rates, Çetinkaya, despite successfully meeting the expectation of controlling the exchange rate, failed to fulfil the expectation of not raising interest rates. As a result, he was dismissed by Presidential Decree number 2019/159, published in the Official Gazette on 6 July 2019, citing his “failure to achieve institutional goals.” On the same day, the decree appointed Murat Uysal, one of the Deputy Chairs of the CBRT, as his replacement.

We should mention that during Çetinkaya’s tenure, the debates on central bank independence in Turkey, which have been ongoing since the beginning of the AKP reign, gained momentum, and his dismissal through a Presidential decree citing “failure to achieve institutional goals” played a significant role in shaping these debates.

Table 1: The BRSA imposed Daily Derivative Transaction Limits with Foreign Counterparties on Local Banks (ratio of total transaction amounts to the latest calculated regulatory capital)

Before delving into the Uysal period, it is noteworthy to mention four new instruments that were incorporated into the CBRT’s toolkit during Çetinkaya’s tenure. The first instrument is the foreign exchange deposits against Turkish lira deposits, introduced on 18 January 2017. The second instrument is the Turkish lira-settled foreign exchange forwards, added on 18 November 2017. Lastly, the third instrument is the Turkish lira currency swaps, implemented on 1 November 2018. The third of these instruments plays a significant role in the ongoing monetary experiment, as we will discuss later.

Additionally, it is worth noting that banks can create foreign exchange forwards to manage their currency risks by combining a spot currency transaction with a currency swap transaction, both with the CBRT, if they choose to do so. The fourth instrument, introduced on 18 June 2019, has been the liquidity facility provided to primary dealer banks through overnight repo transactions at a rate 100 basis points below the policy rate, aimed at supporting the primary dealer system. This instrument was used during Uysal’s tenure and was discontinued immediately after his removal from office.

Since it was known that Uysal, who assumed the CBRT chair on 6 July 2019, worked in harmony with President Erdoğan, no tension regarding interest rates was expected between them. Moreover, a few weeks after the beginning of Uysal’s term, on 31 July 2019, the Federal Reserve ended its quantitative tightening and initiated rate cuts. Furthermore, whether viewed as a curse or a blessing, the arrival of the Covid-19 pandemic and the accompanying economic sudden stop in March 2020 led the Fed to lower its policy rate to zero percent and implement a massive QE programme. As a result, starting from 25 July 2019, Uysal gradually reduced the inherited policy rate from Çetinkaya, which stood at 24%, to 8.25% by 21 May 2020 in nine consecutive steps without encountering significant criticism, at least initially. Indeed, by introducing the above-mentioned primary dealer overnight repo facility interest rate into the interest rate corridor Çetinkaya simplified, Uysal even reduced the CBRT weighted average funding rate to 7.34% by 16 July 2020. Therefore, the Covid-19 pandemic can be viewed as a blessing for Uysal in this regard.

Figure 3: FX Deposits in Local Banks (Monthly Data)

However, the pandemic can also be viewed as a curse for Uysal. Alongside the economic instabilities and financial risks accompanying the pandemic, there was a continued decline in non-resident ownership of TRY-denominated domestic financial assets (both bonds and equities), an intensified deposit dollarisation that began after the August 2018 crisis, as well as a migration of deposits from local banks to offshore banks. Moreover, the rollover of short-term foreign debts became increasingly challenging, adding to the difficulties faced by Uysal. Consequently, Uysal’s grip on the exchange rate eroded, ultimately losing control over it.

Figure 3 illustrates the evolution of the USD/TRY exchange rate from the beginning of 2020 until President Erdoğan removed Uysal on 7 November 2020 with another Presidential decree. What we refer to as the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks Complex, that is, the firm coordination among these institutions in the conduct of the monetary policy, which is still operational today in the ongoing monetary experiment, was born during this period.

In the establishment of the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks Complex, the BRSA took the lead as the first mover. Shortly after the World Health Organisation (WHO) declared the Covid-19 outbreak a Public Health Emergency of International Concern on 30 January 2020, the BRSA implemented a tightening of the swap measure on 9 February 2020, as shown in Table 1. Subsequently, on 11 March 2020, when the WHO declared Covid-19 a pandemic, global financial markets experienced significant turmoil (Öncü, 2020).

During this period, the TRY depreciated by approximately 9% against the USD from 11 March 2020 to 10 April 2020. Responding to the volatility, the BRSA took further action on 12 April 2020 by implementing its most substantial tightening of the swap measure, effectively closing down the offshore TRY swap market, as highlighted in Table 1.

Figure 4: Evolution of the USD/TRY Exchange Rate from the Beginning of 2020 until Uysal’s Dismissal (Daily Data)

However, the TRY depreciation continued, reaching about 13% by 5 May 2020. On that day, the BRSA moved again to limit the total amount of TRY placements, TRY depos, TRY repos, and TRY loans that banks extend to financial institutions located abroad, including their consolidated credit and financial institution affiliates, and branches abroad, to 0.5% of the banks’ latest calculated regulatory capital. These measures, along with the aforementioned tightened swap measure, effectively made the CBRT the FX dealer of the last (and almost only) resort for local banks. As a result of these macroprudential measures, which also serve as capital flow management measures imposed by the BRSA, local banks were unable to fulfil their reserve requirements, hedge their exchange rate risks, and meet their liquidity needs through transactions with banks and other institutions located abroad. Consequently, during Uysal’s tenure, they resorted to meeting these needs through CBRT swaps and spot transactions with the CBRT. It is noteworthy to mention that, to replenish its FX assets, the CBRT signed a swap contract worth 10 billion US dollars with the Central Bank of Qatar during this period, on 20 May 2020. [4]

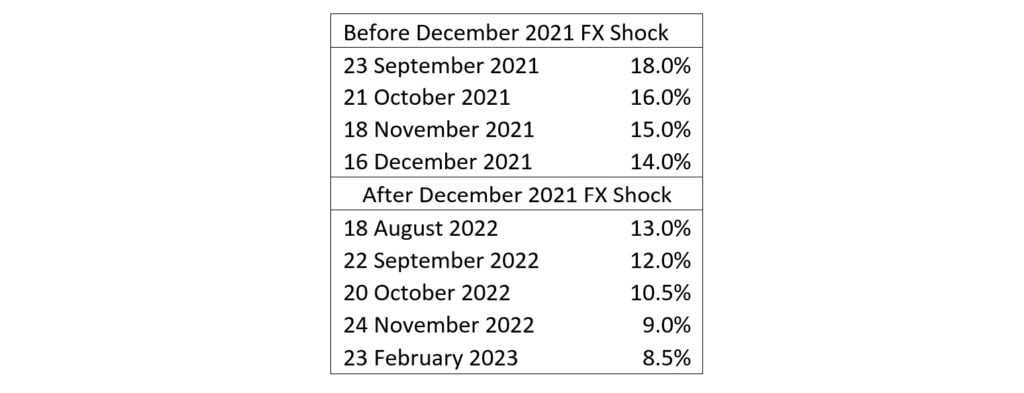

It was after these events, the fact that the USD/TRY exchange rate remained almost fixed at the level of 6.85 lira for a period of 42 days between 18 June 2020 and 28 July 2020, and the deteriorations illustrated in Figure 5 in FX assets and positions of the CBRT that rumours about the CBRT selling foreign currency from the “back door” through State Banks started. Although neither the CBRT nor the State Banks nor the Ministry of Treasury and Finance (MTF) have ever publicly acknowledged this, it is public knowledge that there is a protocol between the MTF and the CBRT that allows the CBRT to direct the State Banks to sell foreign exchange (Bloomberg 2023).

Figure 5: The CBRT FX Assets and Positions (Monthly Data)

Eventually, due to these rumours and the rapid deterioration of the on-balance sheet and net FX positions, Uysal, under heavy political pressure from the opposition, foreign observers, and President Erdoğan, abandoned the 42-day-long hard currency peg depicted in Figure 4. And as of 24 September 2020, he began to raise the policy rate, perhaps unintentionally, signing his own demise. Before his dismissal, Uysal not only raised the policy rate from 8.25% to 10.25% but also introduced further complexity to the simplified interest rate corridor inherited from Çetinkaya. He accomplished this by reintroducing the LLW overnight repo interest rate into the corridor and shifting a majority of the funding to the LLW overnight repo facility. As a result, he raised the weighted average CBRT funding rate to 14% in a disguised manner [5]. And failing to meet President Erdoğan’s expectations of maintaining control over the exchange rate and avoiding raising the policy rate, he was removed from his post by a Presidential decree and replaced by Naci Ağbal on 7 November 2020.

Naci Ağbal is the last Finance Minister during the first presidency of Erdoğan, prior to the transformation of the Finance Ministry into the Ministry of Treasury and Finance in his second term following Turkey’s transition from a parliamentary system to a presidential system in 2017. As of the latest presidential election held on 28 May 2023, Erdoğan has won three presidential terms and is currently serving his third term. Notably, Ağbal is a well-known advocate of the free market, and observers anticipated a return to orthodox policies under his leadership, contrasting the unorthodox approach adopted by the CBRT under Uysal’s leadership and Erdoğan’s pivot towards conventional policies.

And returned Ağbal to conventional policies. First, he reinstated the interest rate corridor that had been simplified under the previous leadership of Çetinkaya. Second, he implemented significant policy rate hikes, raising it from 10.5% to 15% on 19 November 2020, and further to 17% on 24 December 2020. These rate hikes led to a decline in the USD/TRY exchange rate, bringing it down to around 6.90 liras from the inherited level of about 8.50 liras. However, the USD/TRY exchange rate started to climb again in late February 2021. In response, Ağbal raised the policy rate to 19% on 18 March 2021, marking the end of his tenure as the CBRT Chair. On 20 March 2021, by a Presidential decree similar to the one that appointed him, he was dismissed and replaced by Şahap Kavcıoğlu. Ağbal’s tenure lasted just 132 days, the second shortest in the history of the CBRT.

Monetary Policy under Kavcıoğlu

On 20 March 2021, Şahap Kavcıoğlu started his term as the CBRT Chair. As mentioned earlier, Kavcıoğlu is the only chair among former CBRT chairs during the AKP reign who managed to persistently lower the policy interest rate without increasing it ever. Perhaps due to the increased vulnerabilities in global financial markets caused by the Covid-19 pandemic and the volatility in exchange rates following Ağbal’s dismissal, President Erdoğan did not insist on a rate cut during the ongoing Covid-19 lockdown period. Kavcıoğlu adhered to the simplified interest rate corridor during his time as the CBRT Chair and maintained the policy interest rate at 19%, inherited from Ağbal, until August 2021.

As the transition from the Covid-19 lockdown period to normalization approached its end, on 5 August 2021, President Erdoğan’s expected message arrived. Although Kavcıoğlu did not lower the interest rate in the policy meeting on 12 August 2021, he initiated a marathon of interest rate cuts starting from the meeting on 23 September 2021. The interest rate decisions taken by the CBRT under Kavcıoğlu’s leadership from September 2021 to May 2023 are shown in Table 2.

Before the September meeting, the USD/TRY exchange rate, which was around 8.50 liras, surpassed 10 liras prior to the November meeting, and reached as high as 14.50 liras before the December meeting. One day after the meeting, on Friday, 17 December 2021, the USD/TRY exchange rate exceeded 17 liras but closed the week around 16.80 liras after the intervention of the CBRT. However, on Monday, 20 December, it reached another historical record, hitting its highest level at 18.36 liras. As depicted in Figure 1, the monthly percent change in the USD/TRY exchange rate was 21.9% in August 2018, while it escalated to 28.6% in December 2021, indicating that the FX shock in December 2021 was more severe than the one in August 2018.

Table 2: Interest Rate Decisions of the CBRT under Kavcıoğlu

The response of the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks Complex to this shock was the much-debated TRY FX Protected Deposit (FXPD) accounts converted from FX deposit accounts. On 20 December 2021, after the conclusion of the cabinet meeting, President Erdoğan announced the FXPDs, which were promptly announced to the press by the CBRT on 21 December 2021. The FXDPs the CBRT announced were for conversion from USD, EUR, GBP or gold to TRY. Three days later, on 24 December 2021, the MTF (Ministry of Treasury and Finance) announced the introduction of Treasury FXDP accounts, designed to prevent the conversion of TRY deposits into FX deposits by residents.

Lastly, on 31 December 2021, the MTF moved again and issued a directive as an amendment to the CBRT Export Circular requiring that, effective 3 February 2022, at least 25% of the export proceeds attached to the Export Proceeds Acceptance Certificate (EPAC) or the Foreign Exchange Purchase Certificate (FEPC) must be sold to the bank that issued the EPAC or FEPC. Hence, the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks Complex transformed into the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks-MTF Complex.

Before proceeding further, let us compare the August 2018 and December 2021 crises first. In 2018, non-resident ownership of domestic government bonds (although significantly lower than its peak of 23.2% in 2012) remained at 14%, relatively high compared to other developing countries during that period. Non-resident ownership of equities had not deviated from its peak of 65.6% in 2014 and was still around 65%.

Therefore, non-resident investors holding TRY assets had not yet left. Additionally, prior to the August 2018 crisis, the BRSA had not yet imposed its derivatives trading and foreign currency lending restrictions that ease speculative attacks by non-residents on TRY. Non-residents who were able to obtain TRY by means we just described started selling TRY to buy FX. Simultaneously, residents started buying FX assets, leading to a deposit migration from local banks to offshore banks. Due to this heavy selling pressure on TRY, although the transition of residents from TRY deposit accounts to FX deposit accounts (in hard currencies and gold) within local banks also played a role in the August 2018 crisis, this aspect went unnoticed.

By 2021, non-resident equity ownership had fallen below 40%, and it was known that a significant portion of this remaining 40% actually belonged to non-resident Turkish nationals. Non-resident ownership of government bonds dropped below 4% in 2020 and, towards the end of 2021, was around 3%. In other words, there were no significant numbers of non-resident portfolio investors who could create a crisis by selling their TRY assets to buy FX. Additionally, by 2021, the BRSA had closed the offshore swap market and restricted domestic bank lending to non-residents. As a result, the CBRT had become the sole FX dealer for domestic banks, with the State Banks also involved. Therefore, it was not possible for non-residents to obtain sufficient amounts of TRY for a speculative attack on TRY.

Furthermore, through amendments to Decree No. 32 on the Protection of the Value of Turkish Currency mentioned in Cömert and Öncü (2023a), which also regulates foreign payments and offshore money transfers, as well as through official verbal intimidation, the migration of FX deposits from local banks to offshore banks was taken under control. So, what could have been the culprit for the December 2021 FX shock?

The answer to this question lies in the intensified transition of residents from TRY deposit accounts to FX deposit accounts. As detailed in Cömert and Öncü (2023b), when a local bank converts a deposit account in the local currency to a deposit account in a foreign currency at the request of a customer, it creates FX risk because FX liabilities are generated without corresponding FX assets. However, if the FX deposits are created through the extension of FX credits or the purchase of FX assets, there is no FX risk involved. The FX risk arises only when FX liabilities are created without corresponding FX assets, and vice versa.

When the transition of residents from TRY deposit accounts to FX deposit accounts intensified after the 16 December 2021 rate hike by the CBRT, it resulted in a rapid increase in demand by local banks for FX to hedge their FX risk. However, the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks Complex failed to meet the demand quickly enough. As the banks turned to other FX sellers, the USD/TRY exchange rate skyrocketed, leading to the occurrence of the shock. Subsequently, the FXPD intervention took place on 20 December 2021.

We discussed the FXPD accounts in detail in Cömert and Öncü (2023b). Let us conclude this section by mentioning the last important tool introduced by the CBRT-BRSA-State Banks-MTF Complex, along with the previously discussed tools, which enabled Kavcıoğlu to continue lowering the policy rate after the December 2021 FX shock without triggering another FX shock before the 14 May 2023 Presidential and Parliamentary General Elections. Termed as another macroprudential measure, the CBRT implemented this tool in three stages. First, on 23 April 2023, the CBRT extended reserve requirements, which were previously applicable only to the liability side of the balance sheets, to also include the asset side for some loans.

Second, on 10 June 2022, in line with the BIS (2013) Liquidity Coverage Ratio (LCR) proposal, which ensures that banks maintain sufficient unencumbered high-quality liquid assets that can be easily and immediately converted into cash in private markets, banks were required to establish high-quality long-term fixed-rate TRY-denominated government securities as additional collateral for FX reserves to support FX deposits. Last, on 20 August 2022, the CBRT replaced the reserve requirement for loans it imposed on 23 April 2022, with the establishment of long-term fixed-rate TRY-denominated government securities as collateral.

Conclusion

It was with all these bells and whistles, consisting of some macroprudential measures and some macroprudential measures that are also capital flow management measures in the taxonomy of the IMF (n.d.), that the CBRT, under the leadership of Kavcıoğlu, was able to maintain control over the exchange rate and lower the policy rate to meet President Erdoğan’s expectations until the 14 May 2023 Presidential and Parliamentary General Elections. The AKP and its associated coalition won the Parliamentary General Election on 14 May 2023 with a majority in the parliament, and on 28 May 2023, Erdoğan won the second round of the Presidential Election to serve his third term as the President of Turkey. Although whether these bells and whistles can solve Turkey’s structural problems, which we discussed in the second article of the series at length, is debatable. Whether the CBRT is independent or not is also debatable.

What happens during the third presidential term of Erdoğan that started just a few weeks ago, only time will tell. However, it is our firm belief that the Turkish monetary policy experiment we tried to outline in this series, an almost controlled laboratory experiment that could not have been conducted without an authoritarian regime, would help policy makers and ordinary people alike in both developed and developing countries to better evaluate the ongoing monetary policy debates in the age in which deglobalization has become a buzzword.

Hasan Cömert ([email protected]) teaches economics at Trinity College, Hartford Connecticut, US. T. Sabri Öncü ([email protected]) is an economist based in İstanbul, Turkey

References

Acharya, Viral and T. Sabri Öncü (2013): “A Proposal for the Resolution of Systemically Important Assets and Liabilities: The Case of the Repo Market,” International Journal of Central Banking, January.

Aslaner, Oğuz, Uğur Çıplak, Hakan Kara and Doruk Küçüksaraç (2015): “Reserve Option Mechanism: Does it Work as an Automatic Stabilizer?” Central Bank Review, Vol. 15, No 1.

Barro, Robert J. and David B. Gordon (1983): “Rules, Discretion and Reputation in a Model of Monetary Policy,” Journal of Monetary Economics, Vol.12, No 1.

Benlialper, Ahmet and Hasan Cömert (2016): “Implicit Asymmetric Exchange Rate Peg Under Inflation Targeting Regimes: The Case of Turkey,” Cambridge Journal of Economics, Vol. 40, No 6.

BIS (2013): “Basel III: The Liquidity Coverage Ratio and Liquidity Risk Monitoring Tools,” Bank of International Settlements, Accessed at: https://www.bis.org/publ/bcbs238.pdf

Bloomberg (2023): “Turkey State Lenders Return to Lira’s Defence After Sharp Drop,” Bloomberg, Accessed at: https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2023-06-08/turkey-state-lenders-return-to-lira-s-defense-after-sharp-drop

Clement, Piet (2010): “The Term ‘Macroprudential’: Origins and Evolution,” BIS Quarterly Review, March.

Cömert, Hasan (2013), Central Banks and Financial Markets: The Declining Power of US Monetary Policy, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham and Northampton.

Cömert, Hasan (2016), “İmkânsız Üçleme’den İmkânsız İkilem’e: Bretton Woods Dönemi ve Sonrası Para Politikası”, Hacettepe Üniversitesi İktisadi ve İdari Bilimler Fakültesi Dergisi, Vol. 34, No 1.

Cömert, Hasan (2019), “From Trilemma to Dilemma: Monetary Policy after the Bretton Woods”, In Finance Growth and Inequality: Post-Keynesian Perspectives, Eds. Louis-Philippe Rochon and Virginie Monvoisin, Edward Elgar, Cheltenham and Northampton.

Cömert, Hasan and T. Sabri Öncü (2023a): “Monetary Policy Debates in the Age of Deglobalisation: The Turkish Experiment—II,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 58, No 11.

Cömert and Öncü (2023b): “İkili Açmaz Çerçevesinden Türkiye’de Yakın dönem Merkez Bankacılığı ve Kur Krizlerini Anlamak,” ODTÜ Gelişme Dergisi, Vol 50, No 1.

ECB (2023): “Macroprudential Measures,” European Central Bank, Accessed at: https://www.ecb.europa.eu/pub/financial-stability/macroprudential-measures/html/index.en.html

Grabel, Ilene (2003): “International Private Capital Flows and Developing Countries,” in Rethinking Development Economics, Ed. Ha-Jong Chang, Anthem Press, London-New York-Melbourne-Delhi.

Haldane, Andrew G. (2021): “Central Bank Independence – What We Know and What We Don’t,” Norges Bank, Accessed at: https://www.norges-bank.no/bankplassen/arkiv/2021/central-bank-independence-a-practitioners-perspective/

Hetzel, Robert L. and Ralph F. Leach (2001): “The Treasury-Fed Accord: A New Narrative Account,” Federal Reserve Bank of Richmond, Economic Quarterly, Vol. 87, No 1.

IMF (2012): “The Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows – An Institutional View,” International Monetary Fund, Accessed at: https://www.imf.org/en/Publications/Policy-Papers/Issues/2016/12/31/The-Liberalization-and-Management-of-Capital-Flows-An-Institutional-View-PP4720

IMF (n.d.): “Review of Institutional View on the Liberalization and Management of Capital Flows Faqs,” International Monetary Fund, Accessed at: https://www.imf.org/en/About/FAQ/capital-flows

Kydland, Finn E. and Edward C. Prescott (1977): “Rules Rather than Discretion: The Inconsistency of Optimal Plans,” Journal of Political Economy, Vol. 85, No 3.

Öncü, T. Sabri (2020): “Triggering a Global Financial Crisis: Covid-19 as the Last Straw,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 55, No 11.

Öncü, Ahmet and T. Sabri Öncü (2022): “Monetary Policy Debates in the Age of Deglobalisation: Waiting for Deglobalisation—I,” Economic & Political Weekly, Vol 57, No 46.

Palley, Thomas I. (2003): “The Economics of Exchange Rates and the Dollarization Debate: The Case Against Extremes,”, International Journal of Political Economy, Vol 33, No 1.

Rey, Hélène (2013): “Dilemma not Trilemma: The Global Financial Cycle and Monetary Policy Independence,” Proceedings – Economic Policy Symposium – Jackson Hole, Federal Reserve of Kansas City Economic Symposium.

Vernango, Matías (2006): “From Capital Controls to Dollarization: American Hegemony and the US Dollar”, In Monetary Integration and Dollarization, Ed. Matías Vernengo, Edward Elgar Publishing, Cheltenham and Northampton.

Footnotes

[1] Since the rest of the article will mainly rely on the information from Cömert and Öncü (2023b), we will continue without repeatedly referencing it and the references therein to maintain a smoother flow.

[2] LON is the abbreviation of “Late Overnight”.

[3] According to the law, the CBRT cannot engage in borrowing or lending transactions with a maturity longer than 91 days.

[4] The CBRT had also signed swap contracts with the central banks of China, the United Arab Emirates, and South Korea, and opened a depo account with the Development Fund of Saudi Arabia to replenish its FX assets as time progressed.

[5] The CBRT interest rate corridor became the most complex towards the end of his tenure, consisting of five interest rates.

[6] Effective 18 April 2022, the MTF raised this requirement to 40%.