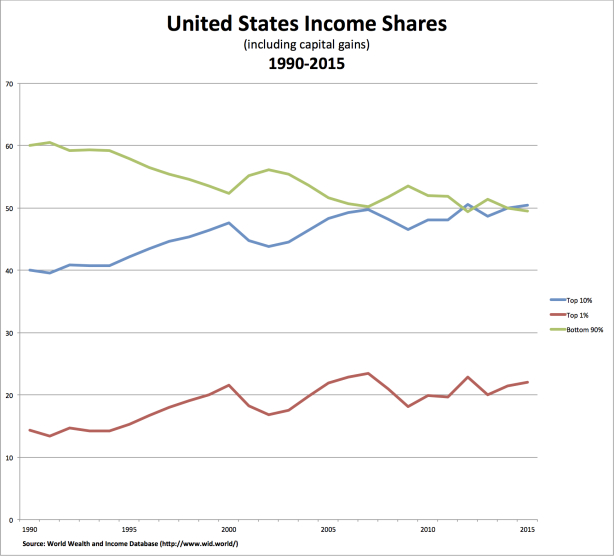

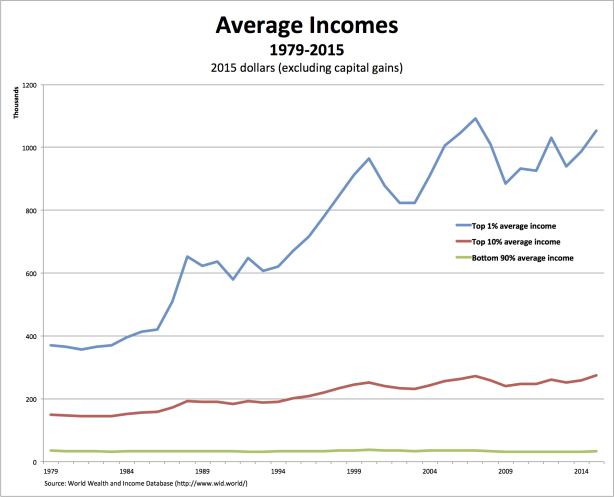

From David Ruccio In a recent New York Times article, Quoctring Bui reveals some fascinating details about the geography of inequality in the United States—including the fact that between 1990 and 2014, the states that we tend to think of as economic engines for the country — like New York, California and New Jersey — are the ones where inequality has grown the most. But the author makes the mistake of repeating the common presumption that, prior to the new millennium (specifically, between 1990 and 2000), income growth was widely shared between rich and poor. When you change the yardsticks to include changes only from the 1990s, the “rising tide lifts all boats” maxim that economists like to talk about seems to hold true. Incomes grew almost across the board, poor to rich; they sag only for the upper middle class. Nothing could be further from the truth. Whether in terms of income shares (in the chart at the top of the post) or average incomes (as in the chart immediately above), the rising tide left the rich richer and everyone else—the bottom 90 percent—falling further and further behind. There simply has been no shared prosperity in the United States—not in the last decade of the last millennium nor in the first decade and a half of this one.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

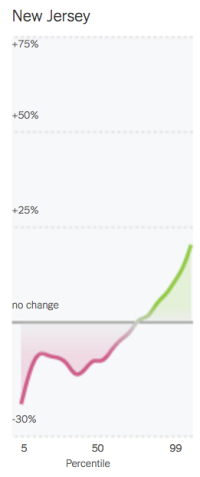

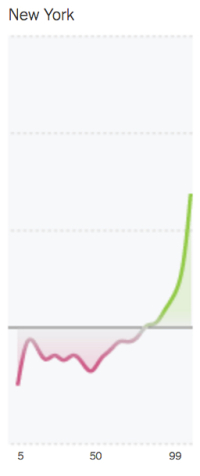

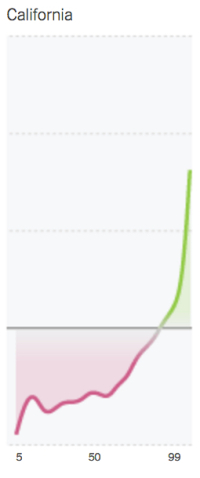

In a recent New York Times article, Quoctring Bui reveals some fascinating details about the geography of inequality in the United States—including the fact that

between 1990 and 2014, the states that we tend to think of as economic engines for the country — like New York, California and New Jersey — are the ones where inequality has grown the most.

But the author makes the mistake of repeating the common presumption that, prior to the new millennium (specifically, between 1990 and 2000), income growth was widely shared between rich and poor.

When you change the yardsticks to include changes only from the 1990s, the “rising tide lifts all boats” maxim that economists like to talk about seems to hold true. Incomes grew almost across the board, poor to rich; they sag only for the upper middle class.

Nothing could be further from the truth. Whether in terms of income shares (in the chart at the top of the post) or average incomes (as in the chart immediately above), the rising tide left the rich richer and everyone else—the bottom 90 percent—falling further and further behind.

There simply has been no shared prosperity in the United States—not in the last decade of the last millennium nor in the first decade and a half of this one.