From David Ruccio The American Dream has all but collapsed under the weight of growing inequality. It’s becoming increasingly difficult for the American working-class to sustain a decent standard of living, and their children are increasingly unlikely to be better off than they are. But those who hang on to the American Dream—or at least the selling of that dream to others—believe that sending young people to the nation’s colleges and universities is the solution. The problem, of course, is that even as enrollment in higher education has grown so has income inequality—and, with it, access to college remains profoundly unequal. The United States is therefore moving further and further away from being able to fulfill the American Dream. According to a new study by Raj Chetty and the rest of the Equality of Opportunity Project team, while the number of children from low-income families attending college rose rapidly over the 2000s—both in absolute numbers and as a share of total college enrollment—the share of students from bottom-quintile families at four-year colleges and selective schools did not change significantly over the 2000s. Even at the Ivy-Plus colleges, which enacted substantial tuition reductions and other outreach policies during this period, the fraction of students from lower quintiles of the parent income distribution did not increase significantly.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The American Dream has all but collapsed under the weight of growing inequality. It’s becoming increasingly difficult for the American working-class to sustain a decent standard of living, and their children are increasingly unlikely to be better off than they are.

But those who hang on to the American Dream—or at least the selling of that dream to others—believe that sending young people to the nation’s colleges and universities is the solution.

The problem, of course, is that even as enrollment in higher education has grown so has income inequality—and, with it, access to college remains profoundly unequal. The United States is therefore moving further and further away from being able to fulfill the American Dream.

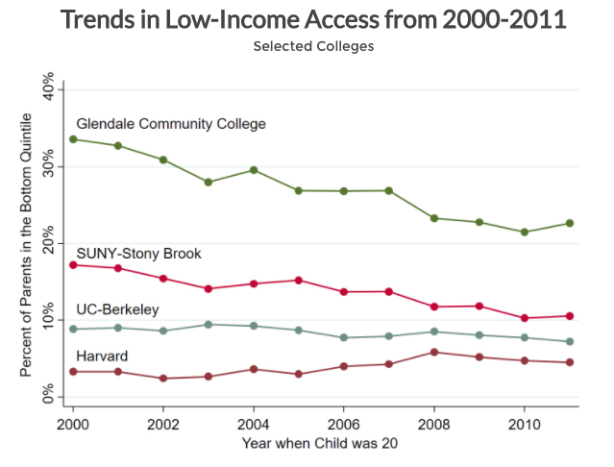

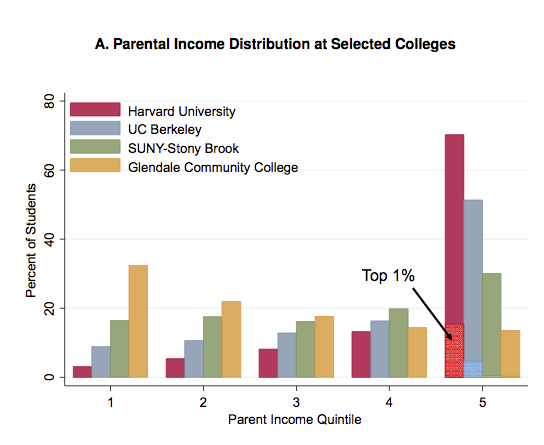

According to a new study by Raj Chetty and the rest of the Equality of Opportunity Project team, while the number of children from low-income families attending college rose rapidly over the 2000s—both in absolute numbers and as a share of total college enrollment—the share of students from bottom-quintile families at four-year colleges and selective schools did not change significantly over the 2000s. Even at the Ivy-Plus colleges, which enacted substantial tuition reductions and other outreach policies during this period, the fraction of students from lower quintiles of the parent income distribution did not increase significantly.* They enroll more students from families in the top 1 percent of the income distribution (14.5 percent) than the bottom half of the income distribution (13.5 percent). And only 3.8 percent of students come from the bottom 20 percent of the income distribution.**

Even at the institutions of higher education with the highest mobility rates (with a high fraction of its students who come from the bottom quintile of the income distribution and end up in the top quintile)—for instance, SUNY-Stony Brook and Glendale Community College—the fraction of students from low-income families fell sharply over the 2000s. As a result, the average student from a low-income family now attends a college with lower success rates than in 2000. In short, the colleges that may have offered many low-income students pathways to success are becoming less accessible to them.

As it turns out, the degree of income segregation across colleges is comparable to income segregation across census tracts in the average American city.

Contrary to the common perception that children interact with a more socioeconomically diverse group of peers when they reach college, colleges in America are just as segregated as the neighborhoods in which children grow up.

Now, it is true: the United States still has a large number of great working-class colleges. For example,

At City College, in Manhattan, 76 percent of students who enrolled in the late 1990s and came from families in the bottom fifth of the income distribution have ended up in the top three-fifths of the distribution. These students entered college poor. They left on their way to the middle class and often the upper middle class.

In fact,

the City University of New York system propelled almost six times as many low-income students into the middle class and beyond as all eight Ivy League campuses, plus Duke, M.I.T., Stanford and Chicago, combined.

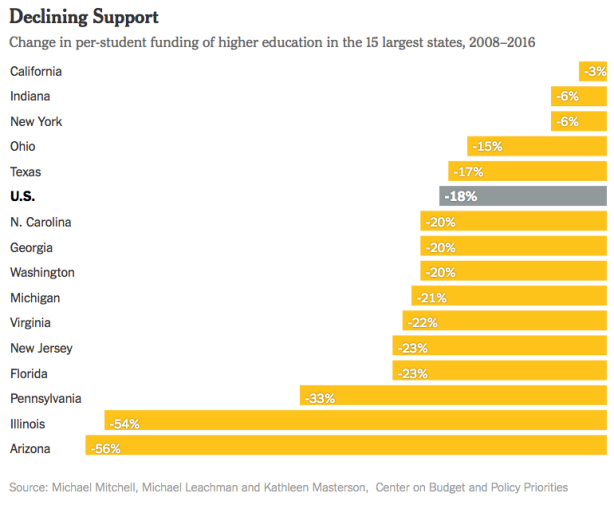

The problem is, the share of low-income students at at many public colleges has fallen over the last 15 years as state funding has plummeted. Working-class students, who remain shut out of the nation’s elite colleges and universities, are finding it increasingly hard to attend and complete their degrees at public institutions.

What we’re left with then is a system of higher education that, outside the elite schools, is not flush with cash and, as a result, is leaving “our young and beautiful students” with less and less access to a high-quality college or university education.

That’s why, continuing to promise the American Dream to the children of the working-class is the real American carnage.

*Ivy-Plus colleges include the eight Ivy League colleges (Brown, Columbia, Cornell, Dartmouth, Harvard, the University of Pennsylvania, Princeton, and Yale), the University of Chicago, Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and Duke.

**At the University of Notre Dame, where I teach, 15.4 percent of students (for the 1991 cohort, approximately the class of 2013) had parents in the top 1 percent, while only 10 percent came from families in the bottom three quintiles.