Long story short: labor productivity, as economists define it, is best understood as the amount of ‘stuff’ the income (wages, profits, rents, interest) related to one hour of work can buy (this is a somewhat idiosyncratic take on productivity. Look however here). Productivity is, as economists define it, not any kind of physical entity. It is supposed to be ‘value added’, or total income cq. the nominal value of net production, per hour of work. For about two centuries, give or take some decades, productivity has increased. Not anymore. At least: in a whole bunch of seemingly quite distinct countries (graph 1). This is, in a historical sense, really surprising. And economists spend a lot of ink about it: why did this happen? Which disease, nay, evil!, did beset the western economies!

Topics:

Merijn T. Knibbe considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

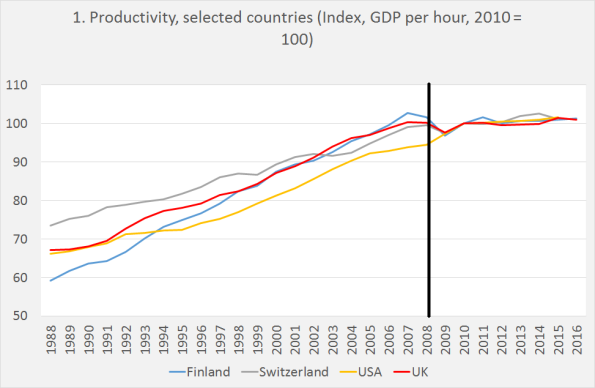

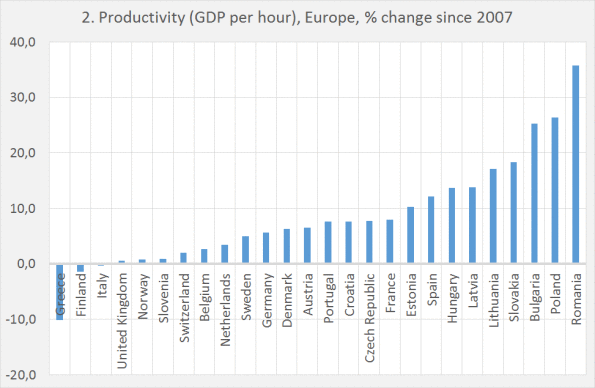

Long story short: labor productivity, as economists define it, is best understood as the amount of ‘stuff’ the income (wages, profits, rents, interest) related to one hour of work can buy (this is a somewhat idiosyncratic take on productivity. Look however here). Productivity is, as economists define it, not any kind of physical entity. It is supposed to be ‘value added’, or total income cq. the nominal value of net production, per hour of work. For about two centuries, give or take some decades, productivity has increased. Not anymore. At least: in a whole bunch of seemingly quite distinct countries (graph 1). This is, in a historical sense, really surprising. And economists spend a lot of ink about it: why did this happen? Which disease, nay, evil!, did beset the western economies! And it does require explanation. For any kind of explanation, however, we still need a more general picture of productivity developments in rich countries (I first wanted to include Japan in graph 1, too, but it turned out that Japanese productivity growth, though low, is clearly superior to these countries). Graph 2 shows developments in most of Europe.

The Greek case is of course engineered. The Troika wanted the Greek to have lower purchasing power and successfully killed of lots of reasonable paid jobs in the medical and the government sector. Italy is a strange case, as the productivity stagnation already dates from around 1990: absolutely weird (though Mexico shows a somewhat comparable development). And quite some countries (Belgium! The Netherlands!) indeed show a dismal track record – at least when compared with preceding centuries and surely when compared with the Post 1948 world. Productivity increases in non-euro Eastern Europe (except the Czech Republic) are however high and comparable with historical developments. Looking at East-European countries it is remarkable that productivity growth in Estonia and Lithuania stalled during the last years. High increases in Spain were due to the demise of the (low productivity) construction sector but recently other sectors seem to have picked up productivity growth, too.

Anyway – productivity stagnation is not an universal pattern. Which does not explain the stagnation in countries where it happened. But it does put the USA/UK/Finland/Switzerland experience in a perspective. A hypothesis might be that declines in ‘real’ wages (Finland! the UK!, the Netherlands!, the USA!) also lead to declines in ‘real’ profits (less spending!) while at the same time a lower interest burden (zero interest policies of central banks) also depresses macro interest income – and therewith the amount of ‘stuff’ total income potentially can buy..