From David Ruccio Recently, I showed that conventional thinking about factor shares has been finally overturned: they are not necessarily constant, especially within existing economic institutions. In fact, labor’s shares have been declining for decades now. The opposite is true of capital’s shares: they’ve been rising for almost three decades. The profit share of national income has, of course, a cyclical (short-term) component. It falls in the period preceding each recession, and begins to rise again during recessions. That’s how capitalism works. But the profit share (illustrated by the blue line in the chart above, measured on the left side) also exhibits secular (longer-term) movements—and, since 1986 (when it reached a low of 7 percent), it more than doubled (to a peak of 15.4

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Recently, I showed that conventional thinking about factor shares has been finally overturned: they are not necessarily constant, especially within existing economic institutions.

In fact, labor’s shares have been declining for decades now.

The opposite is true of capital’s shares: they’ve been rising for almost three decades.

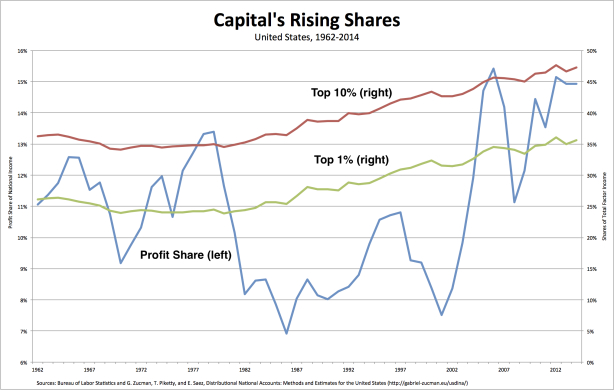

The profit share of national income has, of course, a cyclical (short-term) component. It falls in the period preceding each recession, and begins to rise again during recessions. That’s how capitalism works.

But the profit share (illustrated by the blue line in the chart above, measured on the left side) also exhibits secular (longer-term) movements—and, since 1986 (when it reached a low of 7 percent), it more than doubled (to a peak of 15.4 percent in 2006) and remains still very high (at 13.6 percent in 2016).

Over that same period, the share of income captured by individuals at the top—the top 10 percent and, a smaller group, the top 1 percent (in the red and green lines, respectively, measured on the right)—who receive distributions of the surplus, also increased dramatically. The share of income of the top 10 percent rose by 29.7 percent (from 36.4 to 47.2 percent of total factor income) and of the top 1 percent by even more, 40.2 percent (from 25.4 to 35.6 percent).

To expand the conclusion I reached yesterday: under existing economic institutions, factor shares do in fact change—and they’ve been turning against labor (beginning in the mid-1970s) and in favor of capital (since the mid-198os) for decades now.

That’s a fundamental change in the class nature of the U.S. economy that needs to be reflected in economists’ theoretical models—which also needs to be corrected in reality, by radically transforming existing economic institutions.