From David Ruccio Mainstream economists and politicians have answers for everything. Lose your job? Well, that’s just globalization and technology at work. Not much that can be done about that. And if you still want a job? Then just move to where the jobs are—and make sure your children go to college in order to prepare themselves for the jobs that will be available in the future. The fact is, they’re not particularly good answers. And people know it. That’s why working-class voters are questioning business as usual and registering their protest by supporting—in the case of Brexit, the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the 2017 snap election in Britain, and so on—alternative positions and politicians. On the first point, it’s not simply globalization and technology. Large

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Mainstream economists and politicians have answers for everything.

Lose your job? Well, that’s just globalization and technology at work. Not much that can be done about that.

And if you still want a job? Then just move to where the jobs are—and make sure your children go to college in order to prepare themselves for the jobs that will be available in the future.

The fact is, they’re not particularly good answers. And people know it. That’s why working-class voters are questioning business as usual and registering their protest by supporting—in the case of Brexit, the 2016 U.S. presidential election, the 2017 snap election in Britain, and so on—alternative positions and politicians.

On the first point, it’s not simply globalization and technology. Large corporations, which employ most people, are the ones that decide—in the context of a global economy and by developing and adopting new technologies—when and where some jobs will be destroyed and new ones created. They use the surplus they appropriate from their existing workers and utilize it to determine the pattern of job destruction and creation, in order to get even more surplus.

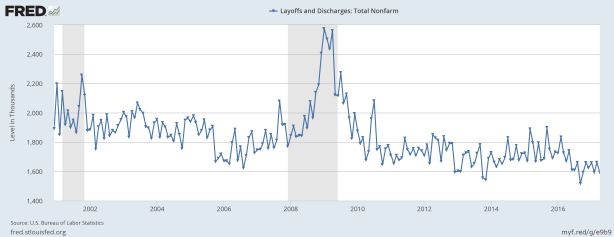

Thus, in April 2017 (according to the data in the chart at the top of the post), employers eliminated 1.6 million jobs in the United States. In January 2009, things were even worse: corporations destroyed 2.6 million jobs across the U.S. economy. Of course, they also create new jobs—often in different companies, industries, regions, and countries. That leaves individual workers with the sole decision of whether or not to chase those jobs, since as a group they have absolutely no say in when or where old jobs are destroyed and new ones created.

What about their children and the advice to go to college? We already know the idea that higher education successfully levels the playing field across students with different backgrounds is a myth (and sending more kids to college doesn’t do much, if anything, to lower inequality).

Now we’re learning that, when states suffer a widespread loss of jobs, the damage extends to the next generation, where college attendance drops among the poorest students.

That’s the conclusion of new research Elizabeth O. Ananat and her coauthors, just published in Science (unfortunately behind a paywall). What they found is that

local job losses can both worsen adolescent mental health and lower academic performance and, thus, can increase income inequality in college attendance, particularly among African-American students and those from the poorest families.

Their argument is that macro-level job losses are best understood as “community-level traumas” that negatively affect the learning ability and the mental health not only of young people who experience job loss within their own families, but also of the other children in states where the destruction of jobs is widespread.

So, the problem can’t be solved by forcing individual workers to have the freedom to chase after jobs and send their children to college. Nor is the predicament confined to the white working-class. In fact, the effects of job losses are similar, but even worse, among African-American youth.

That’s why Ananat argues that

white working class people and African-American working class people are in the same boat due to job destruction. Imagine the policies we could have if folks found common ground over that.

And, I would add, those policies need to go beyond the “active labor market policies”—such as “rigorous job training and active matching of worker skills to employer needs”—the authors, along with mainstream economists and politicians, put forward.*

We also need to reconsider the fact that, within existing economic institutions, employers are the only ones who get to decide when and where jobs are destroyed and created. Giving workers the ability to participate as a group in the decisions about jobs—within existing enterprises and by assisting them to form their own enterprises, would improve their own mental health and that of the members of the wider community.

Such a change would also transform young people’s decisions about whether or not to go to college. It’s not just about jobs in the new economy. It would allow them to demand, as women in Lawrence, Massachusetts did over a century ago, both “bread and roses.”

*Policies to help “disadvantaged workers, especially African Americans, Hispanics and rural residents,” also need to go beyond encouraging the Fed to keep interest-rates low. That still leaves job decisions in the hands of employers.