From David Ruccio Apparently, “late capitalism” is the term that is being widely used to capture and make sense of the irrational and increasingly grotesque features of contemporary economy and society. There’s even a recent novel, A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism, by Peter Mountford. A reader [ht: ra] wrote in wanting to know what I thought about the label, which is admirably surveyed and discussed in a recent Atlantic article by Anne Lowrey. I’ll admit, I’m suspicious of “late capitalism” (like other such catchall phrases), for two main reasons. First, it presumes and invokes a stage theory of development, which relies on identifying certain “laws of motion” of capitalist history. That’s certainly the way Ernest Mandel understood and developed the term—as the latest in a

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

Apparently, “late capitalism” is the term that is being widely used to capture and make sense of the irrational and increasingly grotesque features of contemporary economy and society. There’s even a recent novel, A Young Man’s Guide to Late Capitalism, by Peter Mountford.

A reader [ht: ra] wrote in wanting to know what I thought about the label, which is admirably surveyed and discussed in a recent Atlantic article by Anne Lowrey.

I’ll admit, I’m suspicious of “late capitalism” (like other such catchall phrases), for two main reasons. First, it presumes and invokes a stage theory of development, which relies on identifying certain “laws of motion” of capitalist history. That’s certainly the way Ernest Mandel understood and developed the term—as the latest in a series of necessary stages of capitalist development. For me, the history of capitalism is too contingent and unpredictable to obey such law-like regularity. Second, “late capitalism” is meant to characterize all of a certain stage of economy and society, thereby invoking a notion of totality. Like other such phrases—I’m thinking, in particular, of “globalization,” “empire,” and “neoliberalism”—the idea is that the entire world, or at least what are considered to be its essential elements, can be captured by the term. As I see it, capitalism exists only in some parts of the world, some but certainly not all economic and social spaces, and, even when and where it does exist, it assumes distinct forms and operates in different modalities. Using a term like “late capitalism” tends to iron out all those differences.

So, I’m wary of the notion of “late capitalism,” which for both reasons may lead us astray in terms of making sense of and responding to what is going on in the world today.

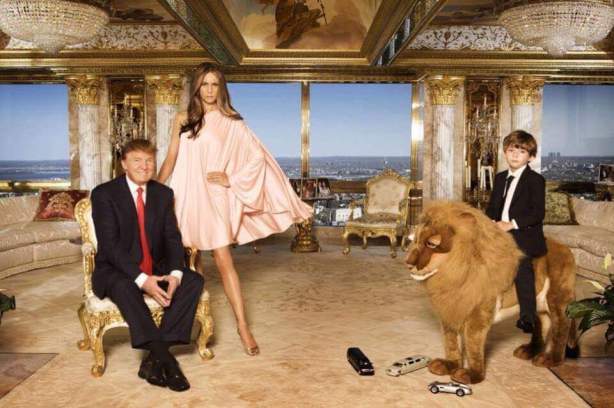

At the same time, I remain sympathetic to the idea that “late capitalism” effectively captures at least some dimensions of contemporary economic and social reality. Here in the United States, there’s clearly something late—both exhausted and exhausting—about contemporary capitalism. In the wake of the worst crises since the first Great Depression, growth rates remains low, leaving millions of workers either unemployed or underemployed. Wages continue to stagnate, even as corporate profits and the stock market soar. And the unequal distribution of income and wealth, having become increasingly obscene in recent decades, has ushered in a new Gilded Age.

As Lowrey explains,

“Late capitalism” became a catchall for incidents that capture the tragicomic inanity and inequity of contemporary capitalism. Nordstrom selling jeans with fake mud on them for $425. Prisoners’ phone calls costing $14 a minute. Starbucks forcing baristas to write “Come Together” on cups due to the fiscal-cliff showdown.

And, of course, the election of Donald Trump.

What is less clear is if “late capitalism” carries with it a hint of revolution, whether it contains something akin to the idea that the contradictions of capitalism create the possibility of a radical alternative. Even if contemporary capitalism is exhausted and we, witnessing and being subjected to its absurdities and indignities, are being exhausted by it—that doesn’t mean “late capitalism” will generate the political forces required for its being replaced by a radically different way of organizing economic and social life.

But perhaps that’s asking too much of the concept. If it merely serves to galvanize new ways of thinking, to recommit us to the task of a “ruthless criticism of everything existing,” then we’ll be moving in the right direction.