From David Ruccio The latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit (pdf) from the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data showed a substantial increase in aggregate household debt balances in the fourth quarter of 2016 and for the year as a whole. As of 31 December 2016, total household debt stood at .58 trillion, an increase of 6 billion (or 1.8 percent) from the third quarter of 2016. Total household debt is now just 0.8 percent ( billion) below its third quarter 2008 peak of .68 trillion, and 12.8 percent above the second quarter 2013 trough. That means the debt loads of Americans will likely surpass the previous peak later this year. Part of the problem is that U.S. workers, whose real wages continue to stagnate, are forced to have the freedom to take on more debt in order to maintain their customary standard of living, for themselves and their families. The other part of the problem is that, while loan delinquency rates are generally declining, the rate for student loans (11.2 percent)—the one form of consumer debt that can’t be erased—is higher than for any other form of consumer debt. Outstanding student loan balances increased by billion, and stood at .31 trillion as of 31 December 2016.

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

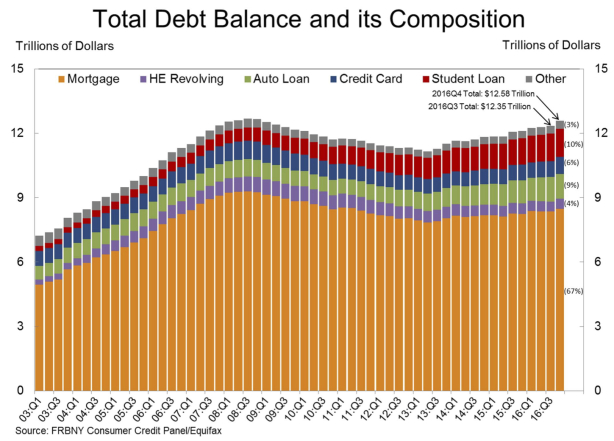

The latest Quarterly Report on Household Debt and Credit (pdf) from the New York Fed’s Center for Microeconomic Data showed a substantial increase in aggregate household debt balances in the fourth quarter of 2016 and for the year as a whole. As of 31 December 2016, total household debt stood at $12.58 trillion, an increase of $226 billion (or 1.8 percent) from the third quarter of 2016. Total household debt is now just 0.8 percent ($99 billion) below its third quarter 2008 peak of $12.68 trillion, and 12.8 percent above the second quarter 2013 trough.

That means the debt loads of Americans will likely surpass the previous peak later this year.

Part of the problem is that U.S. workers, whose real wages continue to stagnate, are forced to have the freedom to take on more debt in order to maintain their customary standard of living, for themselves and their families.

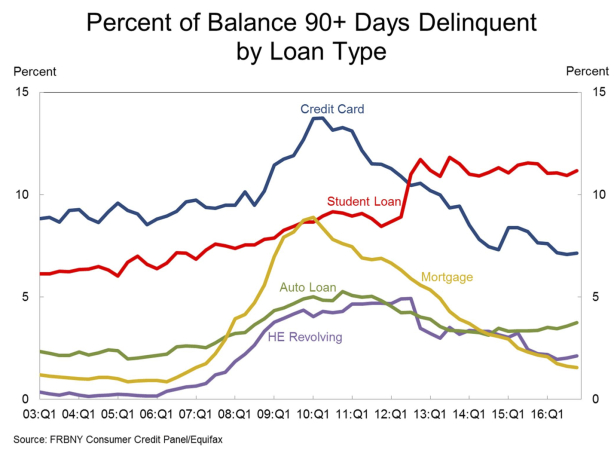

The other part of the problem is that, while loan delinquency rates are generally declining, the rate for student loans (11.2 percent)—the one form of consumer debt that can’t be erased—is higher than for any other form of consumer debt. Outstanding student loan balances increased by $31 billion, and stood at $1.31 trillion as of 31 December 2016.

And, as Derek Thompson explains, the student-debt crisis is most acute not for the much-cited $100,000-debt stories, but for students whose debt burdens are much smaller, many of whom took on a few thousand dollars in debt and didn’t even get a degree.

This is particularly tragic, because these debt-without-degree adults chased the American dream into a dead end.