From David Ruccio The release of the so-called Paradise Papers confirms, with additional names and more salacious details, what we already knew from the Panama Papers and other sources: the world’s wealthy increasingly use offshore tax havens to engage in conspicuous tax evasion. That’s on top of their participation in conspicuous consumption, conspicuous philanthropy, and conspicuous productivity. According to Annette Alstadsæter, Niels Johannesen, and Gabriel Zucman, in a study published before the release of the Paradise Papers, the equivalent of 10 percent of world GDP is held in tax havens globally—and that’s only counting bank deposits, not the portfolios of equities, bonds, and mutual fund shares that wealthy individuals entrust to offshore banks. And, as it turns out, offshore

Topics:

David F. Ruccio considers the following as important: Uncategorized

This could be interesting, too:

tom writes The Ukraine war and Europe’s deepening march of folly

Stavros Mavroudeas writes CfP of Marxist Macroeconomic Modelling workgroup – 18th WAPE Forum, Istanbul August 6-8, 2025

Lars Pålsson Syll writes The pretence-of-knowledge syndrome

Dean Baker writes Crypto and Donald Trump’s strategic baseball card reserve

from David Ruccio

The release of the so-called Paradise Papers confirms, with additional names and more salacious details, what we already knew from the Panama Papers and other sources: the world’s wealthy increasingly use offshore tax havens to engage in conspicuous tax evasion.

That’s on top of their participation in conspicuous consumption, conspicuous philanthropy, and conspicuous productivity.

According to Annette Alstadsæter, Niels Johannesen, and Gabriel Zucman, in a study published before the release of the Paradise Papers, the equivalent of 10 percent of world GDP is held in tax havens globally—and that’s only counting bank deposits, not the portfolios of equities, bonds, and mutual fund shares that wealthy individuals entrust to offshore banks.

And, as it turns out, offshore wealth is extremely concentrated: the top 0.1 percent of richest households own about 80 percent of it, while the top 0.01 percent own about 50 percent of offshore wealth.

So, how does it work? There is a great deal of evidence that the vast majority of offshore wealth, both legal and illegal, is not reported on tax returns. That’s because offshore wealth is done “by combining trusts, foundations, and holding companies, so as to disconnect assets from their beneficial owners.” Thus, tax authorities won’t be able to observe or collect taxes on either the wealth or investment income earned or reported offshore, except in rare circumstances (e.g., a taxable and properly declared inter-generational transfer of assets).

That means the tax burden is shifted onto the rest of us who don’t hold offshore wealth and aren’t able to—or choose not to—engage in conspicuous tax evasion.

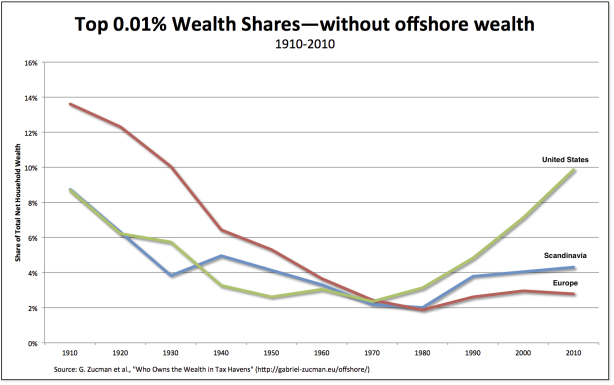

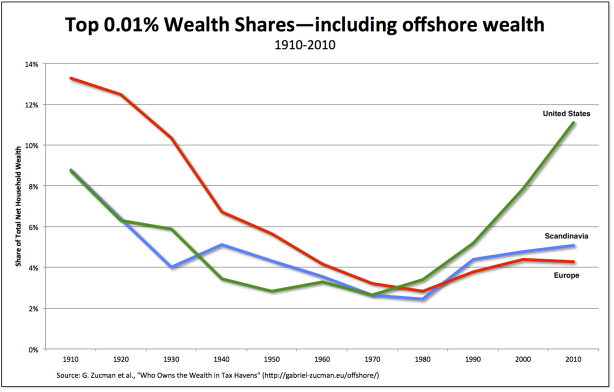

Not surprisingly, accounting for offshore assets increases the top 0.01 percent wealth share substantially. However, the magnitude of the effect varies a lot across countries.

In Scandinavia (Norway, Sweden, and Denmark, the blue lines in the charts above), which does not use tax havens extensively, the top 0.01 percent wealth share rises from about 4 percent to around 5 percent. Offshore holdings have a much larger effect on wealth inequality in Europe (the United Kingdom, France, and Spain, the red lines), where by the estimates of Alstadsæter et al. 30-40 percent of the wealth of the 0.01 percent of richest households is held abroad.

In the United States (the green lines in the charts), offshore wealth also increases inequality but the effect is much more muted than in Europe. That’s only because the U.S. top wealth share is already very high—9.9 percent, without offshore wealth in 2010, compared to 11.1 percent when offshore wealth is included.

Clearly, the world’s wealthiest individuals—including those who call Scandinavia, Europe, and the United States home—have plenty of opportunities via their offshore paradises to engage in conspicuous tax evasion.